Peat beneath our feet

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba, Communications Coordinator

There is peat beneath our feet in wetlands that are thousands of years old. Soil so rich in carbon and history that it’s home to a plethora of plants, animals, and values. Peat forms when a shortage of oxygen in wet soils slows down the breakdown of mosses and other plants. Over thousands of years, layers of organic material build on top of each other, forming peat. We call places with these special soils peatlands.

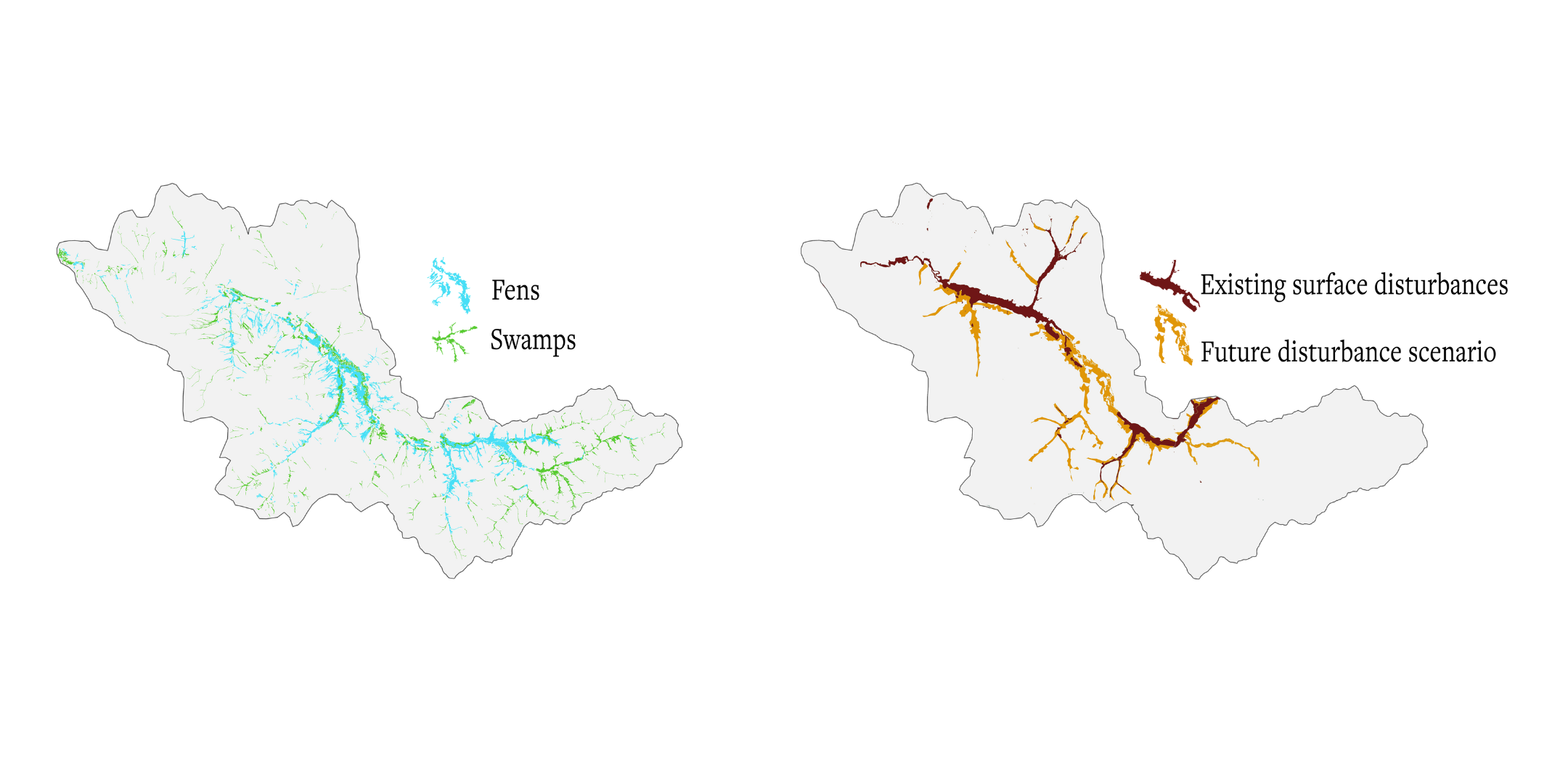

Wetlands with peat come in many forms, like fens, bogs, and swamps.

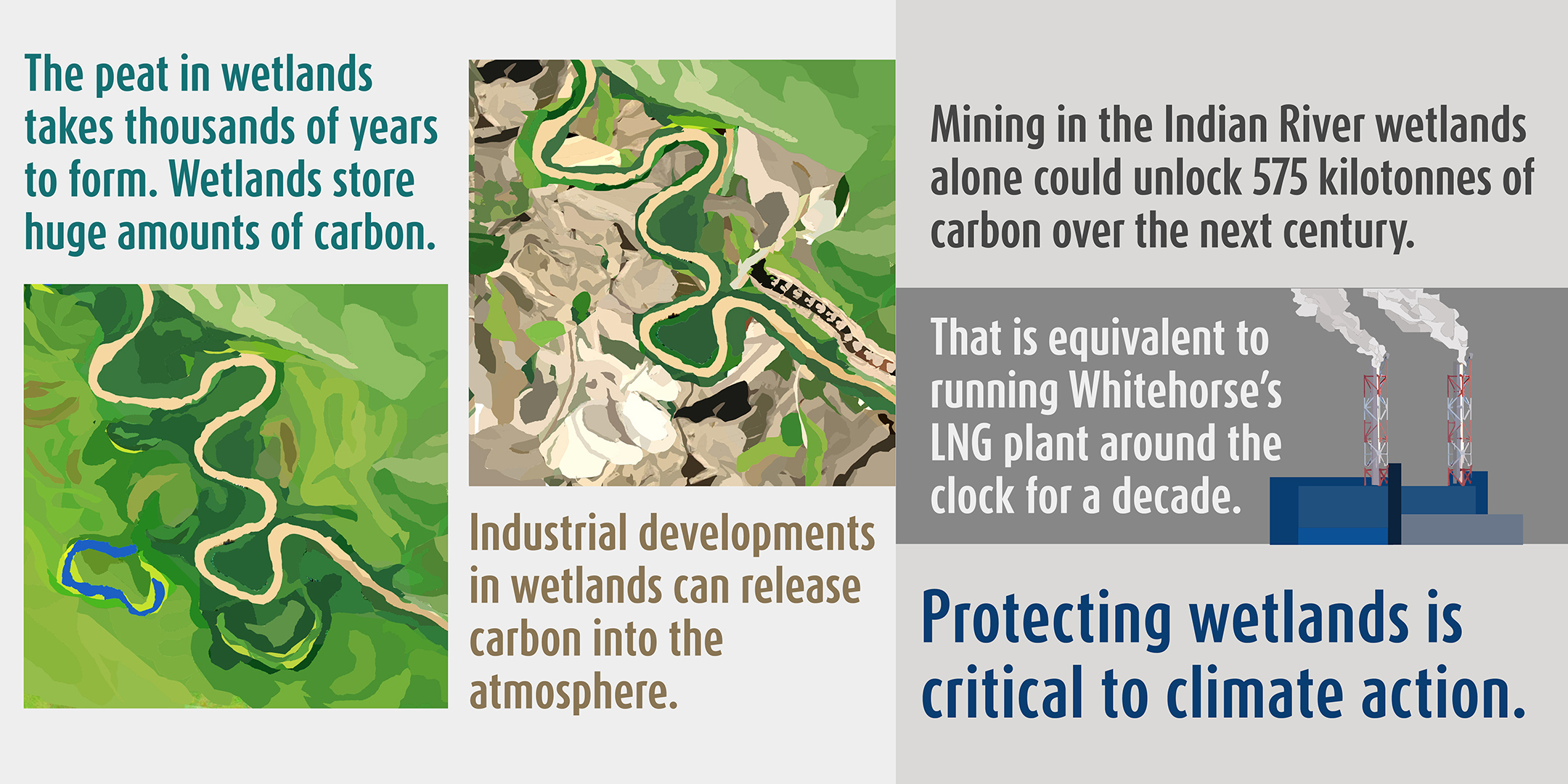

The organic material that peatlands store is rich in carbon. Around the world, peatlands hold more carbon than all the carbon humans have burned since the Industrial Revolution.

Beyond carbon, these ecosystems also hold important ecological and cultural values. They are home to moose, beavers and waterfowl, and a breadbasket for many First Nations citizens. Many people visit wetlands to hunt, fish and feel connected with the natural world.

Will we defeat the peat?

Peatlands are vulnerable to disturbances driven by climate change and industrial development. When disturbed, the carbon they store gets transformed and released as CO2, adding more fuel to the climate crisis.

In the Yukon, placer mining is one form of development that threatens peatlands because gold settles at the bottom of water courses in rivers, creeks and wetlands. When peatlands are excavated, they are all but impossible to restore and never have the same carbon storing potential as intact peatlands.

How much peat is at risk? The short answer is, we don’t fully know. National peatland maps don’t provide a fine scale picture of peatlands in the Yukon, and local mapping of peat has only happened in a few pockets of the territory. Without this information, we don’t know how much of the carbon held by peatlands is vulnerable to all kinds of development.

This makes emissions from peatland disturbance invisible – they don’t appear on the ledgers we use to track carbon emissions and aren’t part of our carbon cutting plans.

Wanting to shed light on these emissions, our team at CPAWS Yukon set out to understand the magnitude of carbon release from industrial development in the territory. Our investigation took us to the Indian River watershed, one of the few places in the Yukon with detailed wetland maps for this type of analysis.

The case of the Indian River watershed

The Indian River watershed lies within the territories of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and the First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun, about fifty kilometres south of Dawson City. The Indian River meanders through a wide valley dominated by fens and swamps.

Peat began forming in the watershed around six thousand years ago—at a time when woolly mammoths still roamed on Siberian islands, and fish had only recently returned to the lakes and rivers around Whitehorse following millennia of glaciation.

We estimate these peatlands store 1,837 kilotonnes of soil carbon—equivalent to over 6,700 kilotonnes of CO2.

The future of the Indian River watershed and its peatlands will be shaped by the outcomes of the Dawson Regional Land Use Plan. The good news is that the Recommended Plan prevents development in bog peatlands, but bogs only make up around 3% of all the peatlands found in the Indian River watershed.

Even with other modest limits on wetland and surface disturbance, the Recommended Plan would allow for significant amounts of new development in most of the Indian River watershed. These disturbances could release 575 kilotonnes of carbon over the next century—about as much carbon as flying a fully loaded jet the circumference of the earth 400 times.

A lot is lost when peatlands are developed. Carbon is released into the atmosphere, habitats are destroyed, and harvesting grounds used for millennia disappear.

While many of the Indian River’s wetlands have been lost forever, it’s not too late to protect those that remain. Join us in speaking up for these ancient wetlands. Public engagement on the Recommended Plan is open until Tuesday December 20.

What this means for the climate

The hundreds of kilotons we estimated could get released from peatlands in the Indian River watershed are from a single industry, in a watershed that makes up only 0.3% of the Yukon.

Peatlands covering three times the area of those in the Indian River overlap with placer claims in other parts of the Dawson Region. Peat is also found patchily across the Yukon: from the Old Crow and the coastal plain in the north, to MacMillan Pass in the east, to the Kluane Plateau and the Southern Lakes. There is a lot of carbon at risk.

But the Yukon’s climate change targets don’t account for carbon emissions from peatland disturbance, even though they are a major source of greenhouse gasses. This problem is not unique to the Yukon, and few countries currently report these kinds of emissions. In the recently released Global Peatland Assessment, the UN Environment Programme called on peat rich countries like Canada to report carbon from peatland disturbance and take urgent action to protect remaining peatlands.

“If we’re serious about acting on climate change, we must get serious about the protection, restoration, and sustainable management of peatlands. Wherever peatlands are allowed to be damaged or drained, harmful emissions will continue to be released for decades,” said Inger Andersen, Executive Director of UNEP.

It’s time for the Yukon to take action to protect peatland ecosystems and the carbon they hold. Protecting these wetlands is critical to climate action.

This blog post is a summary of our CPAWS Yukon peatland report – The Yukon’s Climate Blind Spot. You can find the full report at cpawsyukon.org/publications