From Canada to Colombia: Birds, Belonging, and Big Flight Lessons

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba | May 8, 2025

This spring migration season, TROPICOS Colombia counted 458,031 raptors from 10 species migrating through Ibague, Colombia.

My grandmother has a farm in Colombia, where many Yukon birds migrate for winter. I’ve been fortunate enough to spend time here, lying in a hammock, with binoculars lifted towards the front garden. I remember one time a small warbler, nudging its beak into peeling bark over and over, until it emerged with the biggest grub I’d seen on the farm. This place is special. It has shaped much of who I am, how I think about my identity, and my commitment to conservation. Every time I fly back to Canada, I feel connected to the birds and my journey, both of us call these countries home.

- The front garden in Santander, Colombia, Muisca traditional territory.

- A Blackburnian Warbler on the farm, Muisca traditional territory.

These shared journeys create a story that’s not singular in the North. Almost 90% of Yukon birds are migratory and rely on healthy, connected ecosystems across continents. They travel thousands of kilometres around mountain ranges, over rivers, and through borders to return here to breed. Migration is written into their DNA, etched through generations, through the shape of landscapes, and through the progression of seasons.

I’m always in awe of how they’re able to make those trips. To fly non-stop to New Zealand, Bar-tailed Godwits absorb a quarter of the tissue that makes up their liver, kidneys, and digestive tract into their body through a process called autophagy that lets the body recycle its cells. It’s similar to what bears do to hibernate, except that at the same time Godwits increase the size of their heart and flight muscles to pump more oxygen and have more energy for the 100,000 km flight.

Blackpoll Warblers lay on the fat, altering their digestive tract and gut bacteria so they can process more food and double in weight. They re-absorb and shrink body parts throughout migration, as they burn fat and load up on calories at stop-over sites in Florida and Georgia, USA.

- A Blackpoll Warbler singing at Chasàn Chùa (McIntyre Creek), Kwanlin Dün First Nation and the Ta’an Kwäch’än Council traditional territory. Photo by Malkolm Boorthroyd.

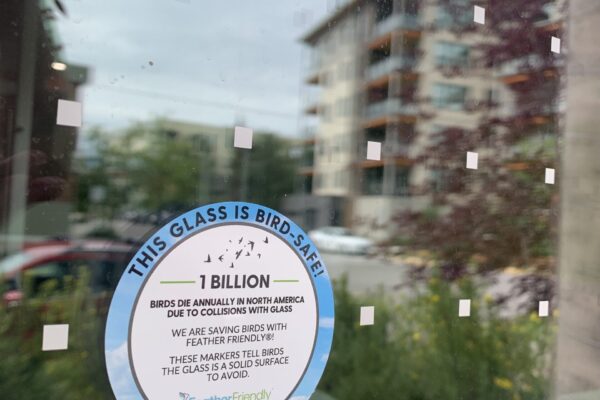

Even with all their incredible adaptations, migratory birds face many challenges. In the Yukon there’s a small bird, a Yellow Warbler; let’s call them Wally. Weighing less than a handful of berries, Wally travels 5,000 km mostly at night from the wetlands of South America to the Yukon. They make it. They flit and flap, searching for the perfect tree to start a nest — when BAM.

“The sky has never hurt before,” Wally thinks.

Dazed and confused, they fall to the ground with a big headache. Someone spots Wally, and takes them to a wildlife rehab where medications help with the pain and swelling. After recovering for a few days, Wally is released on-site where bird dots line the windows to prevent them from colliding. Whenever I see buildings with bird dots, I always think of birds like Wally and reflect on how something so subtle protects a journey thousands of kilometres long. Wally the Yellow Warbler was fortunate; one billion birds die every year from window collisions, mistaking reflections in the glass for the real deal and flying into them.

- Bird dots on the CPAWS Yukon office windows, Kwanlin Dün First Nation and the Ta’an Kwäch’än Council traditional territory. Photo by Paula Gomez Villalba.

- Puffy yellow warbler in Chasàn Chuà (McIntyre Creek), Kwanlin Dün First Nation and the Ta’an Kwäch’än Council traditional territory. Photo by Alex Oberg.

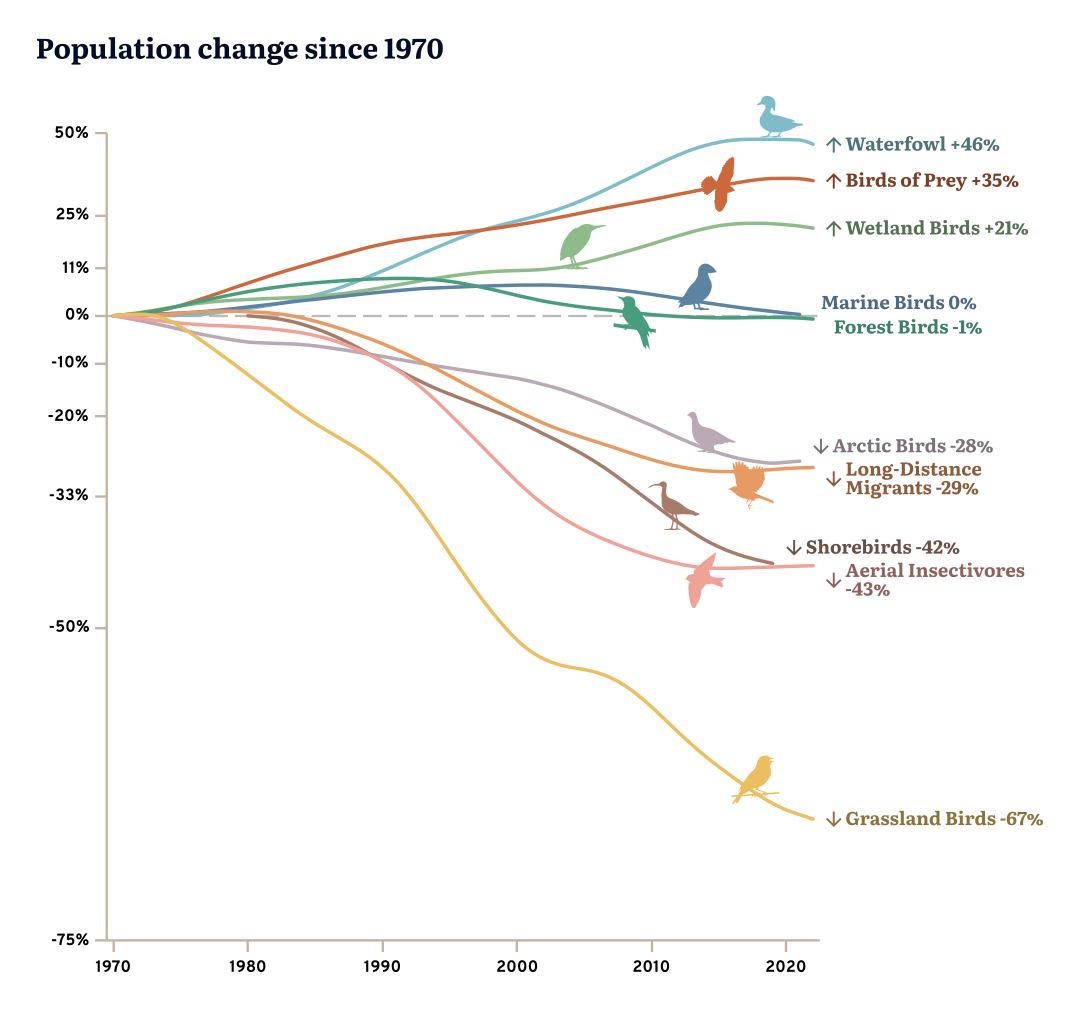

Window collisions aren’t the only challenge Wally and other birds face. Earlier springs due to climate change are confusing and lead many birds to migrate earlier and struggle to find food along the way. Light pollution, outdoor cats, habitat loss, and more add up to have long-term impacts on birds.

This year’s World Migratory Bird Day theme is Shared Spaces: Creating Bird-Friendly Cities and Communities. Like so many wildlife, birds don’t see the borders we’ve drawn around cities and countries. Each migrating bird embodies the history passed down through generations and the deep ties between the world’s ecosystems. The sky is one sky. Their migrations linking tropical wetlands, temperate forests, and northern rivers.

There’s a lot we can learn from migratory birds as we all face the crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. So many birds from the north gather in South America for winter. When food availability is low and risk is high, mixed-species flocks form. Groups of birds come together not to compete, but to cooperate. Some might sound the alarm, others bring the flock together, and some are leaders. Each species contributes something unique to increase their own (and each other’s) chances of survival. In a time of growing division, birds remind us of our shared responsibility.

I’ll be returning to the family farm in Colombia in the fall, excited to see which birds have made it back and wondering how many of them made the journey for the first time. For me, learning about birds helps me better understand and be a part of the ecosystems I live in, and it underscores the need to make choices that honour them. Conservation isn’t just about increasing species numbers or minimizing our presence on the land. It is also about preserving memory, a sense of belonging, and the interactions between plants, waters, and wildlife. Each bird we see highlights not only what is at risk but also what’s still possible.

-

Join CPAWS Yukon and the Yukon Bird Club for a guided walk at Chasàn Chùa (McIntyre Creek) on Thursday May 29th at 6pm. We’ll be looking in the creek and marshes, and walk through the adjacent forest to spot everything from flycatchers to swallows to warblers! We will also be sharing an update in the process for a protected Chasàn Chùa, and how you can advocate for the birds. More details at marshforestflight.eventbrite.com.