“Paddling Home” Along the Stewart River

Written by Nicole Schafenacker with Northern Tuchone (Mayo dialect) language support from Elder Walter Peter and language apprentice Patty Wallingham| January 29, 2026

“These rivers are our bloodlines.”

– Elder Walter Peter

First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun Elder Walter Peter is the first person to speak with Beth and I about the Stewart River in preparation for a 12 day trip where First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk (FNNND) Citizens and staff, and CPAWS Yukon staff will paddle from its headwaters to Fraser Falls. The Stewart River watershed is the heart of FNNND’s traditional territory. Walter describes it as the source from which much of the plant and animal life on the territory stems from.

We will soon experience this natural abundance for ourselves through the amount of wildlife we encounter on the tagé (river). Our trip takes place in the first two weeks of August, or Etthän unän yáanétthän, the month when the moose are getting fat. On our journey we cross paths with: A mother shra dettho (brown bear) with two cubs, the sun glinting off her back as she swims with her young across the channel, dya (cranes) chortling with their prehistoric call, wild geese that trundle beneath the overhang of banks and nets of roots, the mewling cry of agay zhra (wolf pups) early one morning, a tsé’ (beaver) chewing a k’áy (willow) across the bank, the two ta’gok (swans) that glide just ahead of us for days.

“These rivers are our bloodlines,” Walter says again. As we look at the map together he talks about how the confluences between the Stewart and the Nadleen, Lansing, Tsé Tagé (Beaver River), and Hess tell the story of the FNNND family lines and how the tu (water) wove them into the community they are now.

Background: How this Trip Came to Be

We touch down near the headwaters of the Stewart after a 40 minute flight above the braided channels we are about to travel. Ddhaw Cho (Ortell Peak) rises below, its giantess unmistakable even from above. The clouds are dense, and the mix of excitement and nervousness about what lies ahead of us seems mirrored in the dramatic weather blanketing the nän (land) beneath us.

As the Caravan plane lifts off and the whir of its engine evaporates into the distance, Joti, the lead guide on the trip, encourages us to take a few moments to fully arrive here. Standing in the immense quiet with only our dry bags and ourselves is disorienting, like being knocked into a different kind of time and space that slowly opens up before us.

This trip was a collaboration between CPAWS Yukon and the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun. It came about as a way to prepare for the regional land planning process that FNNND will undertake with the Yukon government. It was a means for Citizens to see firsthand the pathways their Ancestors traveled, visit important heritage sites, collect baseline data through water samples, and practice skills to be out on the water and land.

Everyone is here because of the river. Some are directly connected to this land through their Ancestors who have stewarded these lands and waters for generations. Others of us want to help care for this place we feel lucky to call home. Throughout the trip it becomes clearer and clearer how the health of the water touches all other areas of life, including wellness, culture and heritage, economic sustainability, even language, and community.

The beginning: Meeting the Headwaters Head On

On our first evening in camp together we pick up where Beth and I left off with Walter and gather over a map of the watershed. This particular map has been provided by the FNNND Lands Department and marks the sites of different fish camps, hunting camps used for generations and the traplines of FNNND citizens. Now that we are here at the headwaters, we can begin to fathom the scale of this place. We marvel at how community members reached these same places on foot or with dog teams or hand built canoes, and harvested their own food along the way.

As Ronalda later says at the Welcome Home gathering, “Our Ancestors were strong.” The weight of her voice holds the knowledge that will come from 12 days of setting up and taking down camp and traveling 316 km on the water. But for now, we are just figuring out our evening ritual of rigging together a tarp system. Assembling the blue and white striped tarp feels like a kind of a circus trick performed for the quiet audience of trees, tthi (rocks), and water around us.

From morning til night, every camp task will reveal itself as a community effort. With camp assembled, people fed, the toilet hole dug, and tents pitched, Beth, our filmmaker, sets up one of her first shots. She’s waited out the evening until a finger of the river is calm enough to mirror our reflections and the mountain range behind us, in the channel. “Okay, now walk towards me,” she says once the shot is in focus. We walk and chat and blur into liquid and stone.

Our time on the water begins with two days of navigating crisp, shallow headwaters, and learning to identify the thin line between being beached onto gravel bars or washed into fallen ts’ok (spruce) leaning over the water, aka sweepers. Our inflatable canoe is soon decorated with spruce needles. In the bow, Jani’s Matrix style limbo skills improve when we get sucked back into the outer bank beneath a particularly low sweeper. Our shins adapt to their new life on the river of being permanently banged up as we beach, hop out, haul the boat through freezing currents, climb back into the inflatable as gracefully as possible, reposition ourselves, and paddle out. Before long, we are at the foot of Ddhaw Cho where we’ll spend two nights resting, fishing, hiking, eating jak (berries) and drying out clothes.

Patty lays out the language cue cards she’s made especially for this trip to dry in the sun. Each one contains words related to paddling and being on the water in the Mayo dialect of Northern Tuchone, alongside images. The Northern Tuchone language is an oral one and meant to be used in context, she says. The words hold the skills and knowledge that people have learned from the land and water about how to live here in their intonations and structure. Patty shows me how she breaks them down to their roots and how they change based on the relationship between the subject and object. We are in it, the very places where these words originated from.

When we push off from the foot of Ddhaw Cho the days begin to liquefy into a series of eddy turns and ferries in and out. Hours widen as we paddle S turns and horseshoe curves so circuitous they feel existential. We fight the wind blowing us like bath toys off course. We raft up and take floating snack breaks as every minute on the river counts towards the distance we need to make. Rubbing Tiger Balm into sore muscles becomes a part of the morning onshore preparations along with sunscreen and bug spray.

As the river breaks our bodies in, stories begin to burble up: An Auntie that won the rice-sack competition at Beaver Creek hauling a sack hundreds of pounds over kilometres, the grief of losing a family matriarch and the wonder of seeing the same places she saw, stories of how some of us came to live in the Yukon and why this place feels like home. The S turns prompt 20 questions, 2 truths and a lie, science-fiction plots, several renditions of “Just Along the Riverbend,” the birth of a Dolly Parton cover band with a northern flair called Dolly Varden (It could really take off!), and grandiose music video concepts for Marshall’s burgeoning career as a beatboxer. We dole these stories out as rewards for once we get around the next bend. Laurent’s tales especially have us collapsing in “Auntie-laughs,” as Kadrienne calls them, true full-body laughs that remind us that humour, and a good story, are their own kind of sustenance. Yet, beneath our dramatics, we know that this is the tiniest fraction of a glimpse into what people would have experienced traveling this same path without any of the gear, equipment, and comforts we carry. It’s hard to overstate the strength that would have come from surviving even in the best of conditions on this land.

We hit the 100km mark of 316km. Randi, our snack queen, breaks out the birthday cake celebration Oreos that she has managed to keep dry. Despite this treat, the mood is quiet, spent, with kilometres to go before setting up camp. But though we may not feel it, we are getting stronger as individual paddlers and as a group. The long days necessitate feeling into each paddle stroke and learning to be efficient with every angle and fraction of movement. Tracing the current through outer edges of the river bend to gain speed is no longer a training exercise but a necessity. River features like boils, the occasional whirlpool and riffles become our geography, and scanning for sweepers, gravel bars, submerged logs and boulders grows instinctual. I start to feel unsteady on land, as if the current continues circulating in my body long after we’ve stepped on shore. My ankles peel from the long days in neoprene boots that never fully dry and I wonder if we’re slowly becoming amphibious.

Each day that passes we become more streamlined in our movements and scrape away at our own personal “max.” The river widens our edges physically, emotionally, and as a community, pushing us beyond what we thought we could do, sometimes gently, sometimes all at once in a burst of rapids. It sculpts us from the inside out.

The Long Middle: On River Time

We enter canyon walls that appear to be frozen mid topple; columns that once stood vertical look as if they were knocked sideways by the slightest breath of wind. Signs of human time appear through ‘flashes’ of inner bark peeled away on trees. These flashes mark key junctures like settlements, fishing and hunting camps, or burial grounds where people rest in these banks. We paddle close to shore and scan the trees for signs of the cabin Kadrienne and Ronalda’s grandparents built by hand. We see firsthand how the confluences carry a history of people in their depths, a history of the people who navigated these waterways and who eventually became the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun community.

One morning on the water we are jarred by the sight of thaw slumps. The land appears dislocated, like a broken bone or torn ligament, with shelves of earth that are collapsed at odd angles and shoved forward by the melt of permafrost below. What will this land look like generations from now? The noisy exhale of an animal interrupts these fears. Time stills as we spot a water-slick ridge of head and shoulders paddling on the far bank of the river. When the animal turns, revealing teddy-bear ears, we fall silent and watch a bear grow volumes as it heaves itself onto the riverbank, watching us retreat on the belly of the current.

Each day that we travel further south small streams, creeks, and eventually other rivers feed into the Stewart. The river has widened and shapeshifted from serpentine, narrow headwaters into broad dark blue sweeping channels. I think back to the early moment in the trip when Beth captured our group’s reflections in the water. This image feels like a premonition for the ways that we have become intertwined with this place over the last 12 days. The land and water have nourished us as we traveled: River water, wild chives, nintl’át (low bush cranberries), grilled pike, and rhubarb compote have become part of our meals. The tastes of this place recall an echo from the interview with Walter: this river is a source from which all other life on this land springs from.

The fizzing, lapping, and cascading of the water grows into a choral roar, gathering in the distance, when we reach our final stretch. It’s our last morning and though we woke up to the sound of rain on our tents, unrelenting from the day before, we must navigate the last and most challenging rapid before we portage around Fraser Falls to our boat ride back to Mayo.

While the other animals hunker down and out of the rain, we make our way over the rocky shore to scout. The water churns white and green as it narrows towards a chute and we plot our lines.

Kadrienne later reflects on the shifts that took place for her on the river and running the rapid with her cousin Ronalda: “At the beginning of the trip I talked about wanting to find my voice in the stern — a voice that can give direction. Growing up with Ronalda, she knows me as a very timid, shy girl. It was a surprise for her to hear that canoe guide voice come out over the rapids.” She reflects on how finding a calm, clear voice is necessary to negotiate, to lead, to become a matriarch. “Having the full faith from the guides that I was ready to run it, and being able to share that with Citizens and with family…that action was proof of all my growth.”

These four — Kadrienne, Marshall, Patty, and Ronalda — have traveled the path of their Ancestors, through the headwaters to the rapids. They have gathered knowledge about how to be on, and with, the land, about the health of the water, about the Northern Tutchone language that arose from this place, and about their bloodlines. The knowledge of the Stewart River watershed and how it will ripple out through each of us on the trip feels full of possibilities.

Endings are Beginnings: The Future of the Stewart Watershed

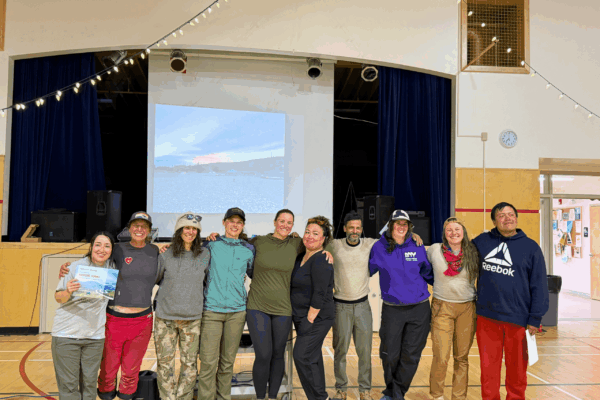

We return to Mayo heading directly to the Community Hall caked in Stewart river mud, still damp from the rain and rapids, in sandals held together with tuck tape. A feast of moose chili and many friendly faces await us: family, friends, Elders, and Leadership. Community. Walter opens the meal with a prayer. How is it possible that 12 days ago he said a prayer to send us off? We are the same people, in the same place we began our journey, and yet we’re not.

Our CPAWS team miraculously pulls together a slide show of pictures to share at the front of the room. The screen flickers on. Though some of these pictures were taken only hours ago they seem to belong to another place and time. A map of the trip route appears and the ten of us gather at the front of the room to speak about our journey. “It felt like paddling home,” says Jani. The river has touched all of us, indelibly, in different ways.

Chief Hope takes the mic and says, “The community has been praying for you all of the days that you were away, and I have to tell you that the day after you left, on July 31st FNNND signed an agreement with the Yukon government to begin regional land use planning.” This is a step that has been decades in the making. It’s a step that will determine the fate of the watershed, and the river we’ve just experienced, stroke by stroke, over the years to come. For some, tears begin to flow as Chief Hope speaks. The trip holds a different kind of weight in light of her words. What was an eventuality has transformed into the “now.” She continues:

“We’re going to need all of you. We’re going to need everybody.”

– Chief Dawna Hope

Northern Tutchone (Mayo dialect) Glossary

Created with language support from Elder Walter Peter and language apprentice Patty Wallingham, with resources Na-Cho Nyäk Dun Northern Tuchone Dictionary via Yukon Native Language Centre and the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun’s Northern Tuchone Language App:

Tsé Tagé – Beaver River

Ddhaw Cho – Ortell Peak

tagé – river

tu – water

nän – land

tthi – rocks

chen – rain

dettho – brown bear

dya – cranes

agay zhra – wolf pups

tsé’ – beaver

ta’gok – swans

k’áy – willow

ts’ok – spruce

jak – berries

nintl’át – low bush cranberries