People of Chasàn Chùa

Art Exhibition

Written by Yataya van Kampen, Conservation Intern | June 19, 2025

Welcome! I am Yataya van Kampen, from the Crow Clan and a member of Champagne and Aishihik First Nations. This art exhibition was my summer-long project as part of my internship with CPAWS Yukon in 2024. When I started at CPAWS and learned that the organization is collaborating with Kwanlin Dün First Nation and Ta’an Kwäch’än Council in its Chasàn Chùa (McIntyre Creek) campaign, I thought this would be a perfect opportunity to highlight people from these First Nations who have deep connections to the area, who have been preserving and caring for Chasàn Chùa for decades. These watercolour portraits are accompanied by a panel about the person or people featured based on interviews I did with them. Square brackets “[ ]” in the panels indicate words added to quotes for clarity.

Humans have been creating art of things that we deem valuable and important (individuals, nature, celebrations, etc) since the beginning. I view art as power—the power to convey significance. My goal from the start of my journey as an artist was to create portraits of First Nations people. There is so little art of First Nations people that accurately represents and celebrates us. A lot of First Nation imagery is created by non-First Nations people who often fabricate a romanticized and inaccurate image that perpetuates racial stereotypes. Through my work, I have always wanted to emphasize that First Nations people are important, and we have the right to be depicted how we truly are.

Environmentalism has predominantly focused on protecting plants and animals, and keeping natural spaces “pristine.” This idea of “pristine” comes from colonization and it excludes people, especially Indigenous people who have been living on their traditional territories for millennia as part of the landscape, equal to the plants and animals. In Kluane National Park, for instance, First Nations were forced off their land to “preserve” the area, unable to legally live or hunt in the park. While this might seem like a thing of the past, there are still many instances where Indigenous knowledge, perspectives, and laws are not valued in environmentalism, especially when they don’t fit the Western scientific model of “truth.” Environmental initiatives such as the Chasàn Chùa campaign must uplift all life, as has been the way of knowing for thousands of years. People are nature too.

See why Chasàn Chùa is an important place to protect for generations to come.

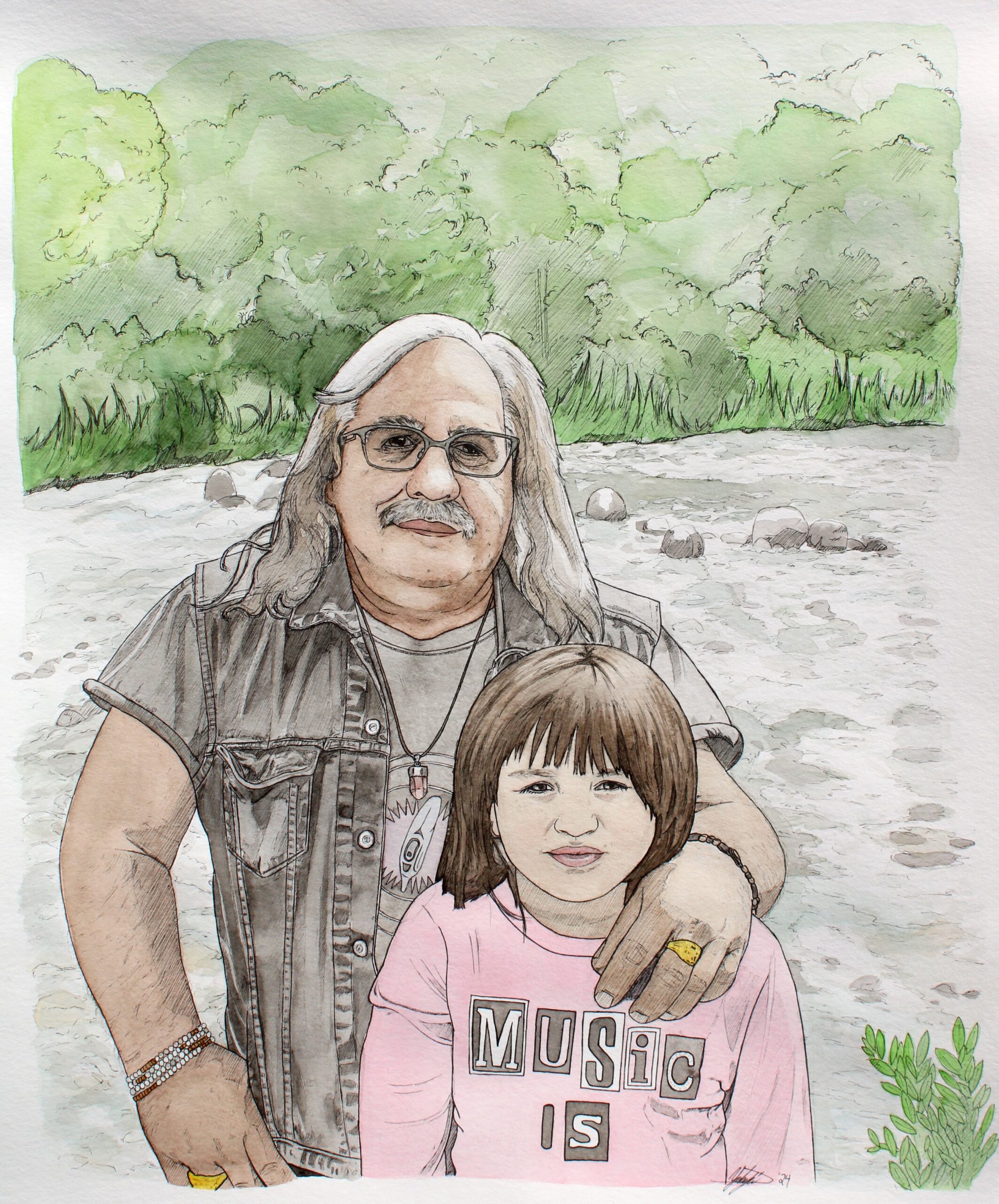

Gary Bailie and Essence Bailie

Wolf Clan, Kwanlin Dün First Nation

Gary Bailie is well known for his volunteer work as founder and head coach of the Kwanlin Koyotes ski program, which is aimed at helping youth and young adults live safe, healthy, and active lifestyles in the McIntyre Subdivision. Passionate about music, Gary also created the Blue Feather Music Festival in 2000 in honour of his late partner, Jolie Angelina McNabb, to uplift young people through music and the arts.

In this portrait, Gary (left) stands before Chasàn Chùa wearing a Blue Feather Music Festival T-shirt. Beside him is his granddaughter, Essence Bailie (aged 9), who is Wolf Clan and a member of Kwanlin Dün First Nation. Gary grew up in the Chasàn Chùa region, although a lot has changed there since he was a boy, he says.

“We spent a lot of time up there [as kids]. We had little trap lines and used to catch mink at the creek. We snared and caught squirrels and rabbits, and ermine. The creek…is quite the little ecosystem. We used to also catch a lot of big fat rainbow trout and grayling. We would make a fire by the creek and cook them right away. It’s a beautiful creek, and it’s very important they protect that waterway [completely] and keep it somewhat wild. Whitehorse prides itself in saying we are the ‘Wilderness City,’ so [we] got to walk the talk now, right?”

“My granddaughter [Essence] said to me last night, ‘Papa, I want to go for a walk somewhere different tomorrow,’” Gary recalled during our conversation. “And I thought about that, and I thought, ‘I am going to take her to McIntyre Creek, because going back there, it is kinda like going home.’”

“I would like my granddaughter to be able to go up there in the future, and take her friends, and say ‘McIntyre Creek, this is a good spot you know? We have to preserve those places,’” he says.

Ruth Massie

Wolf Clan, Ta’an Kwäch’än Council

Ruth Massie was previously Chief of the Ta’an Kwäch’än Council and Grand Chief of the Council of Yukon First Nations. She appears in this portrait in her regalia.

Ruth shares, “[Chasàn Chùa] is in our traditional territory. It was very important when we were growing up, because we used to go down in that area to harvest berries, catch grayling, you know, see wildlife, visit my cousin George Smith, who had a trap line on McIntyre Creek and that whole area.”

While that was true in her youth, things in the creek have changed a lot, she says, and not necessarily for the better.

“It was very, very pristine when we were kids in that area, you know? We could go fishing there. I wouldn’t dare eat a fish in that area now but that’s where the grayling used to come in and go up McIntyre Creek to spawn,” she recalls. “We used to always go with our grandma, or our parents, to hunt small game there: rabbits, gophers, and, of course, the fur always belonged to George (the trapper)…we always saw animals in that area.”

“I really, really think, being so close to the city, [Chasàn Chùa] is even more important today than when we grew up, because the city keeps spreading,” Ruth says. “It’s the home of many, many animals, small and big. I’m glad that we’re trying to preserve that area. I’d like to see it turned into a park, myself, so you have permanent protection.”

“People need to respect the animals,” she says. “They were here first.”

Troy Friday and Elliott Friday

Crow Clan and Wolf Clan, Kwanlin Dün First Nation

Troy Friday (right) is a Youth Outreach & Wilderness Facilitator with Kwanlin Dün First Nation. Here he is with his son, Elliott Friday (aged 5), who is a Kwanlin Dün First Nation citizen. This portrait is based off a photo of Elliott’s first successful moose hunt in 2023.

“When I think of McIntyre Creek, it was the last place I picked berries with my grandma,” shares Troy. “My grandma is June Bruton, a Kwanlin Dün First Nation woman—she is not with us anymore—and I believe McIntyre Creek is important for the Kwanlin Dün First Nation community because of how close it is to town, and how intact the area is. We still use that area for gathering medicine. It’s an area that I use personally, I take youth to it quite a bit. It’s a really easy spot to take an Elder berry picking, [or] a really easy spot to get kids and elders together out on the land, and I really really highlight the importance of that.”

“We can achieve these cultural things within the city limits—being together on the land, coming and learning from each other, without having to travel to Kusawa Lake,” Troy adds. “I grew up in the bush, and I want our son to be a good bush kid, and [to know] how to be just comfortable on the land, right?”

Troy notes Chasàn Chùa is also an important wildlife corridor, allowing larger animals to travel between the Fish Lake area and “not be in someone’s direct backyard” but to be “on the mountain, to travel wherever they wish.” Without development in the area, Troy says, “I believe we might see less moose in Granger, or might see less bears [in the city] if they can just walk through the corridor.”

Pricilla Dawson

Crow Clan, Kwanlin Dün First Nation

Pricilla Dawson is a Native Language teacher at Takhini Elementary School in Whitehorse, and enjoys being out on the land. This portrait shows her out hunting.

“I do a lot of my language teaching on the land,” she says. “A lot of the teaching is based on the land, and that area is important for my students to explore and learn language… So it’s good to have that personal connection to the land [in Chasàn Chùa] for students to explore, and learn language, and feel connected…to do things like harvesting medicine berries, walking, building shelters, hiking, biking, and skiing. Everything I teach can be connected to language and curriculum. When I am teaching on the land, language is everywhere and in everything we do.”

“In the Kwanlin area I feel like we have less and less space now, to practice our traditional ways, such as hunting, fishing, and trapping. That lessens the opportunity for us to teach our future generations our traditional ways of knowing and doing,” Pricilla says.

“It’s good to be out on the land, and to connect to the land, and to feel more grounded when you’re on the land—I do, anyways,” Pricilla adds. “It’s important to keep [Chasàn Chùa] protected, because there’s so much history there with our people, and fishing, and just being on the land doing what we do traditionally.”

George Dawson

Wolf Clan

A well-known community figure, George Dawson had connections with Kwanlin Dün First Nation and Ta’an Kwäch’än Council—he lived and died before the land claims process that would have formally designated him as a member of either. In this portrait, he sits with his traditional regalia, calmly encapsulating who he was: a strong family man, having raised his nine children and many grandchildren while also working on the rivers and land. George passed away in 1989, and although his living family gave their blessing for this portrait to be done, what is written here about him has come from multiple community members, including the artist’s own father and grandmother.

All the people asked to speak about George Dawson strongly identified that he was “a good man.” Within Athabaskan culture, telling someone an individual is a “good person” holds a lot of weight and value. While other cultures, such as Western or Settler cultures, may emphasize things like having a lot of money, success, or good looks, Athabaskan culture places great focus on being kind and generous, and these are the traits people bring to the forefront when they say someone is a “good person.” It is the greatest sign of respect and honour. This focus is especially apparent in Headstone Potlatches, which are the second Potlatch held the year after the death of an individual, when they have fully gone from the Human World to the Spirit World. To prepare for the Potlatch, the deceased person’s Clan saves up money and gifts for a full year; when the Headstone Potlatch occurs, all the money is used to create a big feast and gifts are freely given out. This is only one example out of many where generosity and goodwill are integral to who we are.

“When someone is described in this manner, I always feel it’s worth noting, and this is what I felt with George Dawson,” says Athabaskan artist Yataya van Kampen. “His family knows that he was connected to Chasàn Chùa, so he represents a past generation that not only spent their life on the land, but was truly a part of it.”

More About Yataya

Born and raised in Whitehorse, Yukon I grew up surrounded by nature and have many memories of exploring the Yukon’s nature and communities. At the age of 17, I started living in Europe (Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain) during the winters and coming home for the summers. I went to a Classical Realism art school that taught me how to accurately draw, and recently completed a degree in Sociology that regularly focused on Indigenous topics and perspectives. Because of my time living in large European cities, I have grown a new appreciation for the Yukon’s nature.

The People of Chasàn Chùa art exhibit was co-hosted by CPAWS Yukon and the Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre, running from August 30 to late October, 2024. A big thank you to everyone who helped with the creation of the exhibit – the Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre team, Kate Dawson at Kwanlin Dün First Nation, and all the participants for allowing me to interview and create a portrait of them.

- Opening night of the art exhibit. Photo by Adil Darvesh.

- Yataya shares her gratitude and motivation behind her project. Photo by Adil Darvesh.

- The art spoke to community members, fans of Chasàn Chùa, art enthusiasts, and family members of those featured. Photo by Adil Darvesh.