Standing at the Intersection of Conservation and Food Security

Written by Chris Pinkerton, Executive Director | January 24, 2024

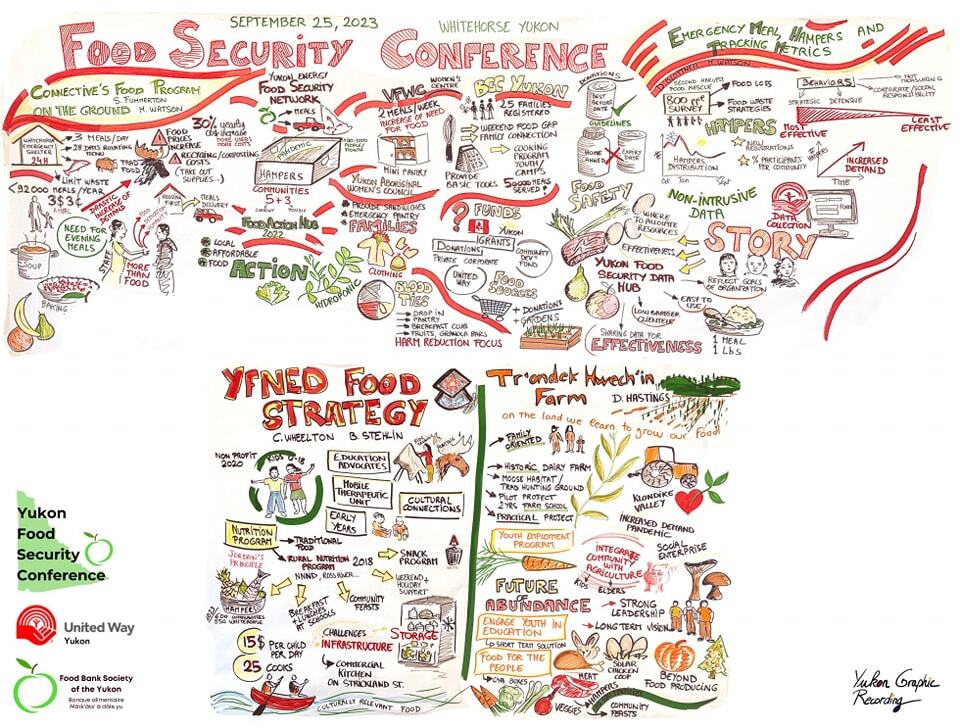

In the Yukon, we’re grappling with a stark reality – we’re the third most food insecure place in Canada. This alarming statistic is not just a number; it’s a pressing issue that concerns all Yukoners. Last September, I had the privilege of presenting at the Yukon Food Security Conference as the master of ceremonies, a conference where food producers, emergency food distribution organizations, community support groups, and local businesses came together here to tackle the current state of food insecurity in the territory. Up until a year ago, I was the coordinator for the Yukon Energy Food Security Network, where I worked collaboratively with Yukon communities, advocating for stronger northern food systems. When I started as Executive Director with CPAWS Yukon in January of 2023, the focus of my work shifted to environmental conservation, but I still felt deeply connected to the work and relationships I had built while advocating for Northern food security.

Photo by Yukon Graphic Recording.

During the well-attended two-day conference held at Yukonstruct, we heard from many inspiring speakers. As we milled about between talks, noshing at the snack table or grabbing a quick cup of coffee, people approached me time and time again to ask me the same question:

“It’s great that you still care so much about food security, but why is CPAWS here?”

On one hand, I can understand the confusion—as a conservation organization dedicated to advocating for the territory’s abundant wild spaces, our mandate doesn’t directly appear to speak to food security or food sovereignty. But when people were asking why CPAWS Yukon would bother attending a conference on food security, what they were really saying was that they didn’t see a connection between environmental conservation and food security. Since taking on my role here at CPAWS Yukon, I’ve found that the exact opposite is true—Northern food security and the protection of wild spaces are deeply interconnected. Environmental factors such as climate change, loss of biodiversity, and sustainable community infrastructure are things we talk about in conservation, but they also affect the food systems that support all Yukoners, regardless of culture or community, although this is especially true when we talk about Indigenous food security.

Here in the Yukon, 98% of the food purchased in stores is trucked up the Alaska Highway. This limited infrastructure means food has to be shipped over long distances to get to northern communities, including Whitehorse. Not only does this make food cost more in the North, especially in more remote communities, but the long travel times and cold winter weather means we often struggle with quality as well as quantity. Likewise, food supplies are at risk of disruption from road closures, whether from a car accident, or—as we’ve increasingly experienced due to climate change—forest fires, flooding, and landslides.

Wildfire along the Stewart River. Photo by Malkolm Boothroyd.

In 2022, for example, we saw the Alaska Highway closed after a creek washout destroyed a section of the road, and in 2023 the heavy fire season temporarily cut off road access to several Yukon communities. When the highways shut down, it doesn’t matter where you live or how much you earn, the grocery store shelves are just as empty.

Climate change and habitat loss is impacting the Yukon, with some populations of Yukon salmon, sheep, moose, and caribou in steep decline. Beyond the potential for severe ecological impacts, this also has direct, and sometimes dire, effects on Northern food security. This is especially true for First Nations, some of whom—like the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and the Forty-Mile Caribou Herd or Kluane First Nation and Dall sheep—have voluntarily reduced or canceled hunting or fishing for culturally important species which they have often relied on for subsistence for generations.

Fortymile Caribou Herd. Photo by Malkolm Boothroyd.

Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to have healthy and culturally appropriate foods produced through socially just, ecologically sound, and sustainable methods. It speaks to the collective right to define one’s own policies, strategies, and systems for food production, distribution, and consumption. We heard about the importance of this from experts at the conference in September. Derek Hasting spoke on the success story of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Farm, which provides local fresh food to Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in citizens, and Clifford Gladue of White Fish Lake First Nation talked about his work to bring traditional foods into schools in Northern Alberta. Many spoke directly about the importance of the access to land, ‘wild’ or otherwise, for both food sovereignty and security.

Moreover, troubling numbers from the Food Bank Society of the Yukon (formerly the Whitehorse Food Bank) have shown an unprecedented increase in demand, with food distribution and client numbers almost doubling since 2020. Food insecurity is a growing issue affecting all Yukoners, not just those living in more remote areas. As an added note, since the COVID-19 pandemic, the Yukon Food Bank has also been shipping food to Carmacks, Faro, Atlin, Haines Junction (and surrounding area), and Watson Lake.

From the conservation side at CPAWS Yukon, it’s hard even to say that we look at it through a different lens. When our team talks, we speak to land sovereignty and the need to steward and protect the land from the pressures of industry and climate change. When staff visit Yukon communities, we hear stories about generations of cultural values and history, and the health benefits that come from connecting to the land. Our conversations are often about respecting the land because it’s where food was harvested to feed communities and raise healthy families. We hear about the value of traditional foods, of moose, caribou, and salmon. We’re told stories about places to hunt, or fish, and places to harvest plants or medicines, and the importance of these things for strong food systems and community wellness. We are taught that the salmon and caribou are keystone species – impacting the health of the land and the water. And we mourn that some communities who once relied on salmon for food are now unable to fish their rivers or to teach their children their history or values at fish camp. Some are even buying and importing fish so community members can have just a taste of their culture and tradition.

Canoe Culture Camp co-organized by the Yukon First Nation Education Directorate, First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun, and CPAWS Yukon. Photo by Malkolm Boothroyd.

Our work makes it clear that community health, food security, land and water conservation, climate change, and biodiversity loss are all interconnected. As Yukoners, we can’t pick and choose to look selectively at only one part and expect to “fix” anything. When we look at food security (and sovereignty) along with the conservation of wild spaces as two sides of the same coin, we move forward in safeguarding landscapes that protect the well-being of the people who live on them, and vice versa.

If you want to learn more about conservation or food security please reach out to CPAWS Yukon, the Food Bank Society of the Yukon, or the Yukon Energy Food Security Network.