Mining 101: Digging into the terms

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba, Communications Coordinator. Photos by Makolm Boothroyd.

April 6, 2023

Across much of the Yukon, boreal forests and wetlands stretch as far as the eye can see, crisscrossed by ancestral rivers that provide for the land, people, and wildlife. Threatening these rich wild spaces is the legacy of the Klondike Gold Rush, which lives on in the territory’s mining laws. These laws date back to the 1900s and prioritize short-term gains, reflecting the extractive history of colonialism on Indigenous land.

Now the Yukon government is creating a new minerals legislation, in collaboration with Yukon and Transboundary First Nations. The new mining legislation will cover the entire life of placer and quartz/hardrock mines, from prospecting to production to closure.

This is a once in a generation opportunity, so we want to make it as accessible as possible for you to share your vision for mining in the Yukon. Even if you’re not a mining expert, you’re an expert on your hopes and vision for the territory’s future. Mining has shaped and will continue to shape the Yukon, and this legislation needs to prioritize the territory’s long-term health and prosperity.

There are lots of terms, synonyms, and potential approaches related to mineral development. Here we’ll define some common mining terms you might come across. Once you’re ready to take action, check out our guide to completing the official survey. Responses will be used by the Yukon government as they continue developing the legislation.

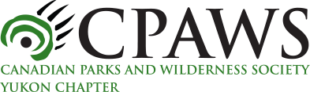

Placer Mining: Placer mining is a way of extracting minerals (usually gold) that has settled in the bottom of water courses like rivers, creeks, and wetlands.

These minerals often lie beneath frozen layers of soil and gravel requiring miners to use excavators, bulldozers, and pressurized water to strip away vegetation, soil, and let the permafrost thaw.

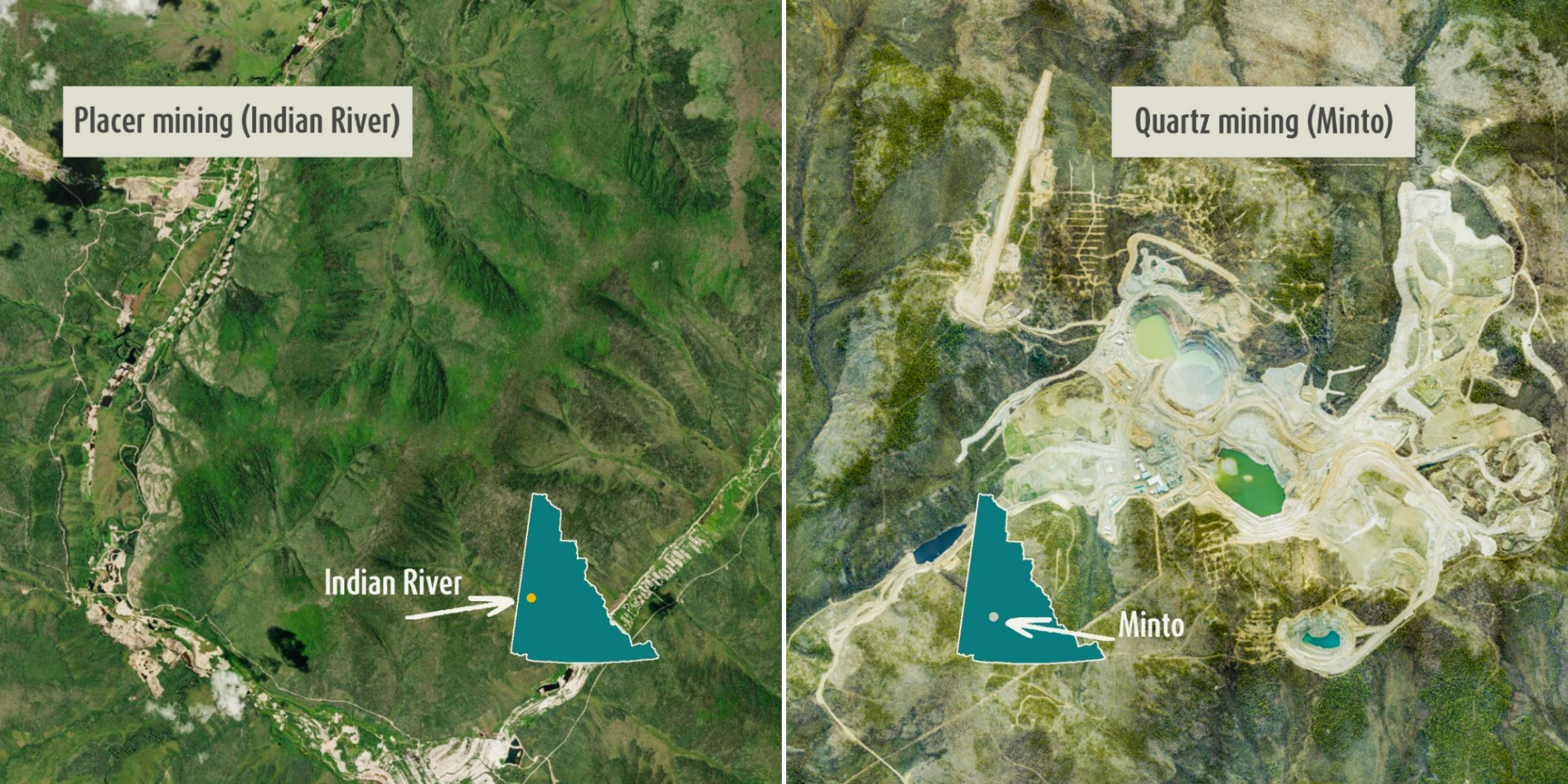

Quartz/Hardrock Mining: Hardrock mining is where mining companies extract minerals from bedrock veins using large open pit or underground mines.

Extracting minerals from the rock often involves the use of chemicals that can be harmful if released.

Images from Google Earth. Graphic by Malkolm Boothroyd.

Prospect of profit, or automatic land rights?

Free Entry System: Free entry grants any individual or company the right to stake a mining claim without the need for a permit or other authorization.

Mineral rights are automatically approved without consultation or consent from First Nations. These mining claims then hold tremendous leverage over land use planning decisions.

Acquisition: Rules about who can stake a claim and how.

Currently any adult can do so by pounding a few stakes into the ground and paying a $10 fee. Part of the free entry system.

Disposition: Rules for where mineral staking can happen and what mineral rights are granted.

Prospectors can stake a claim anywhere, unless the area has been withdrawn from staking (like designated protected areas). Part of the free entry system.

Mineral Tenure/Mining Claim: When an individual or company has tenure or a claim, they hold the rights to explore and develop minerals below the claim.

These are acquired through the free entry system and have to be maintained in good standing.

Exploration: Evaluating the mining potential of an area where a company has mining claims.

Exploration can involve building roads and cutting trails, disturbing wildlife with daily flights, building camps, and moving tens of thousands of tonnes of rock. Claim holders automatically have the right to explore, but specific exploration projects are subject to approval.

Mining roads cover Arch Mountain in the Kluane Wildlife Sanctuary.

Accounting for harm and public benefits

Financial Security: Hardrock (and a few placer) mining companies provide financial security to cover the costs of reclaiming and closing their mine site in case they abandon it.

This security amount is paid before production begins and reassessed every 2 years. The Yukon has a long track record of underestimating security needed, leading to expensive taxpayer funded cleanups and environmental harm left unsecured.

Royalties: Royalties are payments made to governments by mining companies, recognizing that the public and First Nations own the rights to minerals and should benefit from their extraction.

Placer miners currently pay just 37.5¢ per ounce of gold (the same rate as the early 1900s) and quartz miners are only required to make payments once they start making a profit.

Tailings: Tailings are waste materials left over after mining and can include harmful chemicals and metals.

Hardrock tailings are left in large ponds or are sometimes dried and stacked. Reclaiming tailings is a challenging task and some tailings will require treatment indefinitely.

Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board (YESAB): YESAB is responsible for reviewing proposed mining projects, and recommending mitigations and whether or not a project should go ahead to the Yukon government.

The YESAB process is separate from the new mining legislation but links very closely to it.

Abandoned Wellgreen quartz mine, clean-up costs are an estimated $15 million.

A changed landscape

Reclamation: Reclamation involves transitioning land to a different state after exploration and mining ends.

It’s usually impossible to fully restore the original ecosystem – simply too much has changed. The result is a different landscape where original values have been restored, replaced, or lost to different extents. Reclamation can involve filling in pits, recontouring the landscape, and planting vegetation. It’s expensive and hard to enforce, sometimes resulting in mines being abandoned.

Peat: Peat is a carbon-rich soil found in some wetlands that takes thousands of years to form.

Peatlands are vulnerable to placer mining because gold settles at the bottom or rivers and wetlands. When excavated, the peat decays and releases massive amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. Peatlands cannot be restored.

Permafrost: Permafrost is frozen soil that holds huge stores of greenhouse gasses like methane and carbon dioxide.

Typically we would say that permafrost is soil that is frozen year-round, but climate change and developments like mining are causing permafrost thaw.

Closure: The goal of mine closure is to return the site to a stable, non-polluting state and to meet reclamation goals.

This process takes many years. In the Yukon, a hardrock mine is considered closed when a Closure Certificate has been issued. Despite the number of mines that have operated in the territory, none have received this certificate.

Abandonment: When a mining company leaves a site without meeting the proper reclamation or closure measures.

Abandoned mines can pose significant risks to people and the environment, as contaminants and equipment are left unchecked. Reclamation and closure is then handled by the Yukon government with public funds.

The stages of placer mining show how in spite of the best reclamation efforts, natural peatlands can’t be restored.