Seeing With Our Own Eyes

Gladiator Metals Copper Claims around the City of Whitehorse

Written by Stephanie Woods, Conservation Coordinator | December 6, 2023

“It breaks my heart to see this. I’ve been hiking and biking here for 30 years. I’ve seen bears, caribou, snowshoe hares, wolverine tracks—all sorts of animals and birds. Yes, there’s some disturbance here but it’s not meant to be permanent. But disturbance is how the steamroller starts. People come and say ‘let’s do more.’”

– Sandy Johnston

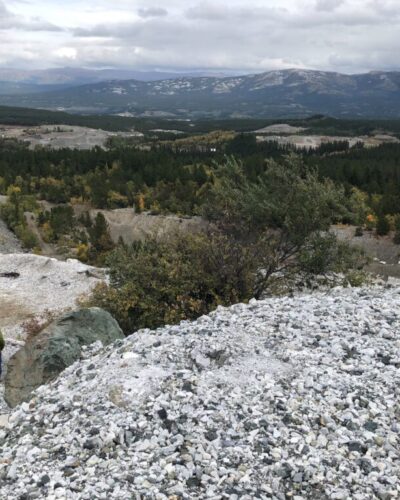

Sitting behind the wheel of his well-traveled red pickup truck, Sandy Johnston drove us along rough backroads, passing piles of copper-laced blue waste rock, leftovers from the long history of copper mining in this area. All around us, highly flammable coniferous trees like spruce and pine had been removed or mulched as a part of a firebreak the Yukon Government has been installing around the perimeter of Whitehorse. Sandy sighed: the firebreak, which has required much of the forest to be removed and the ecosystem dramatically altered, has been a hard compromise for the communities of Cowley Creek, Mary Lake, Wolf Creek, and Mt. Sima. Although it was a tough sacrifice to make, Sandy, a long-time resident of Mary Lake, explained it is a necessary sacrifice to protect the city from the increasing risk of wildfire, and he’s optimistic the area will eventually recover from the disturbance.

He isn’t, however, as optimistic about the area’s ability to recover from a new copper exploration project and potential mine proposed by Gladiator Metals. The claims are within the traditional territories of Kwanlin Dün First Nation and Ta’an Kwäch’än Council, and near Carcross Tagish First Nation Settlement Land. Leading up to this excursion with Sandy, CPAWS Yukon heard from citizens of south Whitehorse concerned about the threat this project poses to the watersheds, landscapes, and wildlife that migrate through this area—and their own backyards.

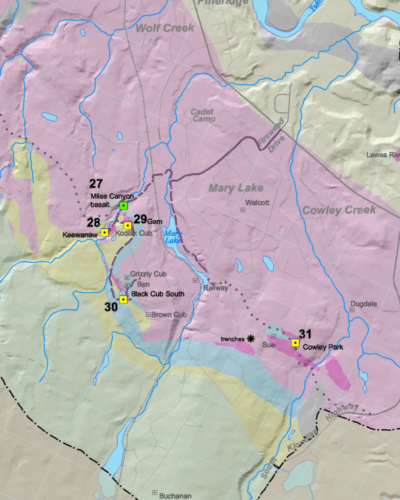

In November 2022, Gladiator Metals, a mineral exploration company, acquired the Whitehorse Copper Project, a series of 314 claims spread throughout 5,380 hectares within the Whitehorse Mining District. The company’s claims stretch along the south and western shoulder-side of Whitehorse, from Cowley Creek, through Chasàn Chùa (McIntyre Creek), all the way to Crestview, falling within the historic Whitehorse Copper Belt, which was first discovered in 1897 and actively mined mostly between 1967 and 1982.

- Copper minerals in stone. Photo by Stephanie Woods.

- Sandy and Randi navigating at a site. Photo by Stephanie Woods.

- Mining claim. Photo by Adil Darvesh.

- Zoomed Whitehorse Copper Belt map. Created by Yukon government.

The southernmost claims are located close to the Cowley Creek neighbourhood and encroach on the neighbouring forests and beloved trails.

A long-time Yukoner and member of our board here at CPAWS Yukon, Sandy has a powerful depth of knowledge and genuine concern for the places within and adjacent to Whitehorse that are threatened by continued mining exploration. From our perspective, and that of many others within his community, Sandy is an active steward of this area he has come to know intimately, and his family has grown deep roots within its soil. On this day, Sandy rounded up some of our team–Adil Darvesh, Randi Newton, and myself–on a crisp early autumn morning to show us exactly what’s at stake.

We rumbled down the rough road, yellowing aspens and poplars shimmering in the distance, towards the first site we wanted to visit–Black Cub South. Black Cub South (locally known as the “Big Quarry”) is a former mining pit and now a current exploration target three kilometres west of the Cowley Creek neighbourhood. It is one of thirty-one historical mining turned current exploration sites through the project, each of which is known by its historical Whitehorse Copper Belt name.

A pit first mined in 1971 that has since filled with water and reflected a vibrant blue met us at the site. The colouration is likely due to copper carbonates released from previous mining. Black Cub South had clear signs of being used as a recreational site with a year-round trail network. A male bufflehead treaded gracefully through the water. Fireweed, wild rose, buffalo berry, and small bog cranberry lined the edges of the pit and neighbouring forest, revealing the native forest understory. Next, we traveled to Keewanaw (known locally as the “Small Quarry”), another old site last operational in 1971 and now a target for Gladiator Metals, where we walked the trails of mining past, seeing an old mining pit left and filled in with water, large areas of land cleared, and skeletons of machinery left behind. We listened to the rushing of water traveling over cobbles and the soothing sound of Wolf Creek, adjacent to the pit along the side of a rock road used for incoming and outgoing traffic.

- Drone view of Cowley Creek and its surrounding wetlands. Photo by Adil Darvesh.

- Old mining pit at Keewanaw. Photo by Stephanie Woods.

- Keewanaw. Photo by Stephanie Woods.

From there, we headed north to our final site of the day, Arctic Chief. The most disturbed site we had seen yet—Arctic Chief hosted a large open pit peppered with scrap metals, an old car, and garbage. Vegetation was sparse here as we overlooked the city limits. We had become quieter as the afternoon went on and we absorbed the emotional impact of what mining so close to town would mean, in a stressed ecosystem that hasn’t yet had enough time to recover.

- Deep thinking overlooking the pit. Photo by Stephanie Woods.

- The Arctic Chief, a landscape shaped by waste rock. Photo by Randi Newton.

- Sandy, Randy and Stephanie at the Arctic Chief site. Photo by Adil Darvesh.

There’s a delicate balance to be had between ecosystem recovery and community access to these environments, providing places not only to walk, relax, and play, but also to harvest traditional medicinal plants and foods, like yarrow, cranberries, and rosehips. This balance would quickly be lost with continued mineral exploration or resumed mining activities.

Mining exploration would bring in large and loud machinery, the noise of which has been well-documented to impact wildlife and the way they use disturbed areas. Exploration activities at Black Cub South will further fragment the remaining forests and vegetation not already impacted by the firebreak, and can have long-lasting impacts to water quality on the surface and in the groundwater system. Speaking for myself, it’s hard to envision further mining exploration in an area that is clearly trying to recover, an area that is important to so many: humans, animals, and plants alike.

There’s a tendency for people, companies, and governments to look at a place like Black Cub South and undervalue it because it isn’t ‘pristine’ anymore—it’s already been disturbed by industrial and human activities, so what’s the harm in a little more? This perspective not only undervalues the ecological and community value of recovering environments but is also a slippery slope, says Sandy.

“Steamrolling ahead once an ecosystem is already disturbed can act as a gateway for further environmental destruction”

– Sandy Johnston

Personally, after working for parks and protected spaces around human settlements at both the municipal and federal levels, I’ve seen this first hand: healthy ecosystems degraded from overuse and development leading to severe habitat fragmentation–and sadly, very sadly in some cases, the complete loss of an ecosystem. Stressed ecosystems on the borders of large urban centers do not need more ground disturbance, noisy machinery, human traffic, vegetation loss, or water contamination—they need protection, restoration, and stewardship to recover.

Further mining exploration and potential future activity around the city’s perimeter will further stress these locally treasured places. Gladiator Metals has already recommenced drilling activities at the Cowley Park target by late September. They have most recently been issued a Class I exploration permit for diamond drilling on some of their claims within city limits. As concerned citizens and local residents, your voices are important. Join the Citizens Concerned about the Copperbelt Facebook group, a space that brings the community together to share concerns and stories, ask questions, and learn more. We will continue to keep our ears to the ground, support community members, and advocate for the health of shared landscapes, wildlife, medicinal plants, and sacred water.