What the Heap? Understanding the cyanide disaster at Eagle Mine

What the Heap?

Understanding the cyanide disaster at Eagle Mine

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba and Nicole Schafenacker | March 7, 2025

On June 24, 2024, the heap leach at Victoria’s Gold’s Eagle Mine near Mayo, Yukon, on the traditional territory of the First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun (FNNND), failed, causing a slide that released 300,000 cubic meters of cyanide-contaminated water into the ecosystem.

The cycle that kept hundreds of millions of litres of toxic solution contained broke.

Victoria Gold was unprepared for the crisis, and in the months following the disaster failed to take adequate steps to mitigate the damage, while their financial prospects tanked. Late last summer a court put Victoria Gold into receivership, transferring control of the mine site and the company’s finances to more competent hands. Still, there are huge challenges to overcome, like containing the contaminated water, keeping storage ponds from leaking and overflowing, and stabilizing what remains of the heap leach.

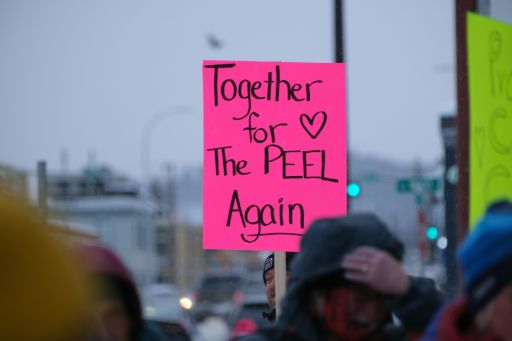

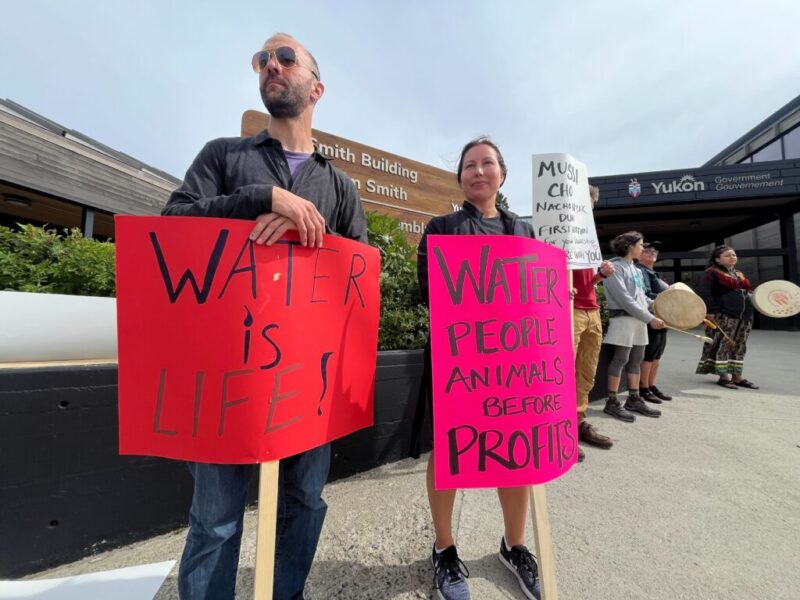

This disaster is yet the latest example showing the Yukon is far behind when it comes to responsible mining. A public inquiry can help us change that. We must understand what policies, decisions, and actions from government and Victoria Gold management led to this disaster.

Water contaminated with cyanide and heavy metals is still seeping into the ground. It has reached local waterways, including Haggart Creek in the South McQuesten watershed, home to grayling, and Yukon River Salmon.

Here, in the South McQuesten River watershed, people fish, hunt, and pick berries. Moose and grizzly bears care for their young, and thousands of birds find refuge during migration. There is no doubt that this disaster will change how people interact with the area.

Quotes from CBC News feature by Julien Greene highlighting people who live near the Eagle Mine Disaster site: Troubled water.

-

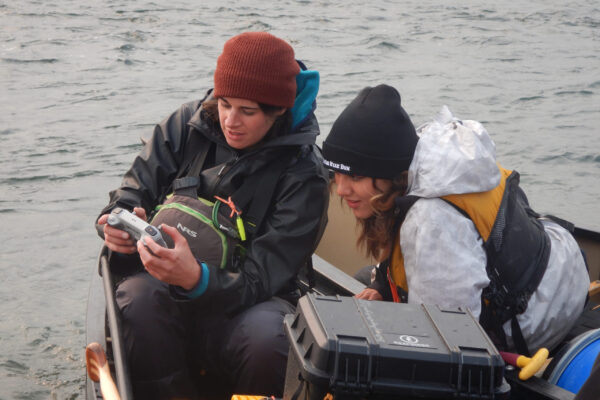

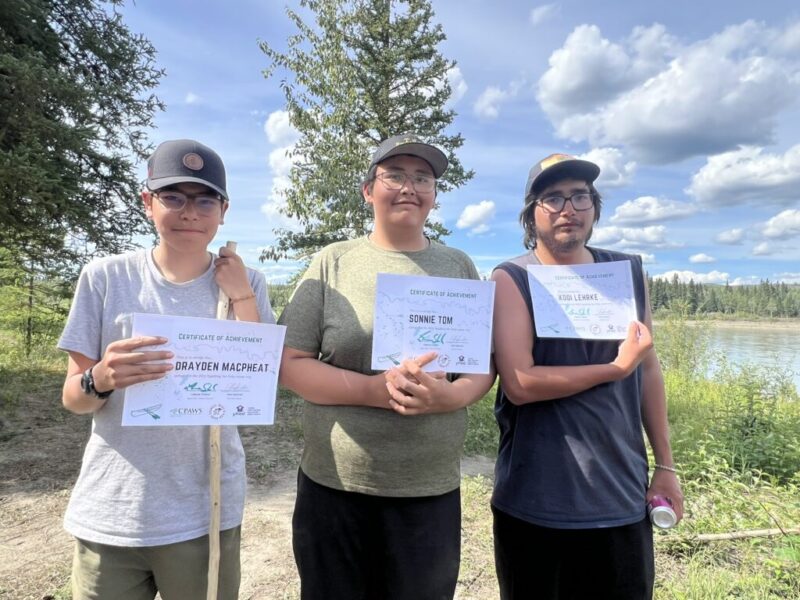

In the disaster, the mine’s heap leach facility, a huge pile of rock over which cyanide solution is cycled to extract gold from the ore, failed. The resulting slide and damage to the facility released over 300,000 cubic metres of cyanide-contaminated water into the ecosystem. A month after the initial failure, the territorial government stepped in to begin groundwater interception, and later a full response coordinated by the territorial government with the FNNND emergency response team and federal government.

Even now, eight months later, cyanide is still infiltrating into the environment, with leaks recently reported from a ruptured pipe and from a storage pond meant to contain contaminated water.

Victoria Gold, the owner of Eagle Mine, had a history of violations, unrealized plans, and broken promises, and repeatedly failing to follow the requirements of their operating licenses or meet deadlines to bring the site into compliance. Mining failures like this should never happen again.

“Yukon Government has a lax approach to permitting, compliance, monitoring, and enforcement of mineral activity in the Yukon, and this approach was reflected in YG’s oversight-or lack thereof-of the Eagle Gold Mine… [including] allowing Victoria Gold Corp to operate the Heap Leach Facility without proven cyanide treatment capacity, contrary to the conditions of its Water Use Licence” — First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun letter to the Auditor General of Canada

There are a lot of questions unanswered, and a public inquiry is the only way forward to give the South McQuesten watershed the justice and respect it deserves. Tell Yukon government there must be a public inquiry.