Where We Stand on the Arctic Refuge and What You Can Do

Written by Laurence Fox, Campaigns Coordinator | October 25, 2023

A shortened version of this post appeared in the Wednesday, October 18th, 2023 edition of the Yukon News.

The cancellation of the remaining leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge this past September was, and is, wonderful news for the Porcupine Caribou, the Gwich’in which have worked tirelessly to protect them, and everyone who loves, cares for, and wants to preserve wild places.

What comes next, though, for the Arctic Refuge?

Honestly? That’s hard to say. It’s a complicated process, legally and politically speaking. Where we’re at with the Arctic Refuge is largely contained within an 800-plus page report written in a mix of industrial mining jargon, data sets, and legally-nebulous bureaucratese that the average person needs a pot of black coffee and a thermal lance to break into, which certainly doesn’t make understanding things any easier. Having spent the last three weeks up to my eyeballs in this report I can tell you, however, that the nuts and bolts of the situation is this:

If you care about the Porcupine Caribou, wildlife conservation, climate change, First Nation rights and sovereignty, Canadian-American relations, the fundamental principles of democracy, or any combination thereof you should be paying attention to this.

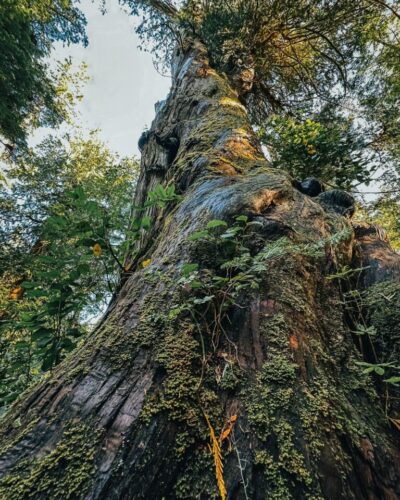

Photo by Peter Mather.

Here’s why:

Way back in 2017, the Trump Administration passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which, as the name implies, was mostly about cutting taxes and creating jobs in the name of incentivizing economic growth. As you would quite reasonably expect, cutting taxes means less money for government spending, and the Tax Act was expected to cost around US$1.9 trillion, or about the same as the total GDP of Canada for the same year.

To help offset the upfront costs of this, the Trump Administration slapped a rider on the tail end of the Tax Act (page 182 of 185, specifically) authorizing the sale of oil and gas leases in the “1002 Area” of the Coastal Plains within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge–around 1.5 million acres of sea-swept, mountain-rimmed Northern wilderness which also happens to contain the calving grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd, sacred to the Gwich’in.

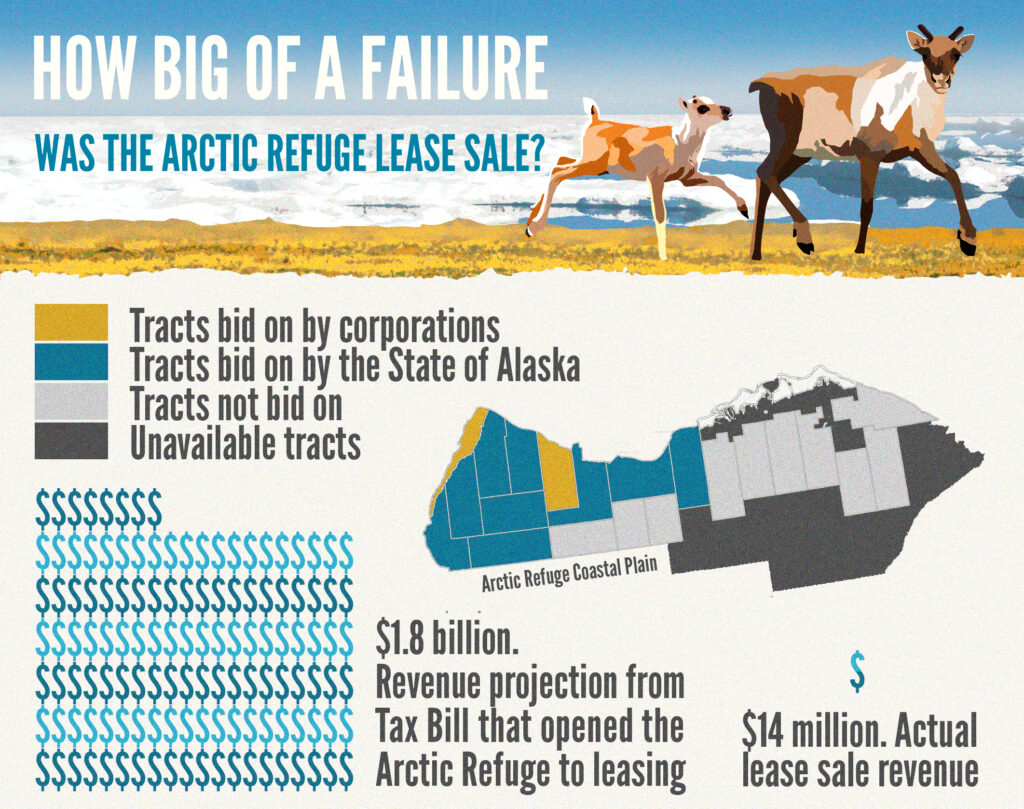

(Not to spoil the ending for you, but the first round of lease sales generated a paltry US$16.5 million, or about one percent of what had been expected.)

To make these lease sales happen, however, the legislation which governs the Arctic Refuge, had to be altered. Prior to 2017, the Arctic Refuge had four express purposes: to conserve animals and plants in their natural diversity, to ensure a place for subsistence hunting and gathering activities, to protect water quality and quantity, and to fulfill international wildlife treaty obligations. When it passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the Trump Administration added a fifth; to “provide for an oil and gas leasing program within the Coastal Plain.”

The Act also directs the Secretary of the Interior to “establish and administer a competitive oil and gas program for the leasing, development, production, and transportation of oil and gas in and from the Coastal Plains,” making it a legal obligation to ensure lease sales happen.

What that means is that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act makes oil and gas leasing an express, legal purpose of the refuge, regardless of who the President or the Secretary of Interior is. To this end, it specifies not only how much of the area must be put up for oil and gas leasing– a minimum of 400,000 acres, or an area about the size of Tombstone Territorial Park–but also requires no less than two leasing sales be held, the second of which must be held no later than December 2024.

In other words, the U.S. government unilaterally decided to not only start an oil and gas leasing program in the middle of a wildlife refuge, a move in direct conflict with the original intentions of the Arctic Refuge, smack dab in the middle of the Porcupine Caribou Herd’s calving grounds, but made it illegal not to do so.

Under American law, when something like oil and gas leasing in the Arctic Refuge is proposed, it triggers the need for an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). An EIS assesses the potential impacts of a project on both people and the environment and then makes recommendations about whether or not that project should proceed, and with what mitigations in place. Moreover, the government agency proposing the project is in charge of compiling the EIS and deciding if what it wants to do is okay after the EIS is complete. Although all projects have to work within Federal, state, and local environmental laws, it’s up to the agency–in this case, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM)– to determine their application within its EIS.

An EIS is supposed to look at all the potential environmental and human costs and benefits of a project, design ‘alternatives’–imaginary scenarios used to create baseline expectations about how a project might impact an area under differing development situations–consult scientists, experts and the community about those situations, and then make a decision based on those alternatives and the feedback around them. In this case, however, the administration wasn’t looking at whether or not the leases should be issued, but under what conditions they would be issued.

The Trump Administration had made it a foregone conclusion that those leases had to be offered up for sale, whether anyone wanted them to be sold (or wanted to buy them) or not.

If this sounds a bit like telling students to turn in their homework, grade their own assignments, and then decide if they’ve passed or failed the course, that’s only because it is– and that’s exactly what happened with the initial EIS issued in 2019 under the Trump Administration.

The 2019 EIS ultimately recommended all 1.5 million acres of the Coastal Plains be put up for leasing, with the fewest restrictions and the most aggressive development options possible. Most of the recently canceled leases–there were seven of them, all held by the State of Alaska, a handful and a half of the 11 sold in early 2021–were all issued under the original EIS. That EIS was, as you would expect, found to be so legally, methodically, and scientifically flawed that the Biden Administration ordered the whole thing binned like Tuesday’s tuna sandwich on a Friday afternoon.

One of the first things incoming-President Joe Biden did in 2021 was throw a hold on all development in the Arctic Refuge and order a Supplementary Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) be undertaken. This SEIS restarted the consultation process–if not from square one then from square two or three–which technically makes it a mulligan more than a “supplement.”

This brings us to where we are now, being asked to comment a second time on an environmental assessment which is inherently flawed because it legally has to conclude that leasing in the Arctic Refuge will take place.

Okay… so now what?

Okay… so now what?

The bad news is that there’s no way to stop the lease sale–no matter what happens, they are going to put a minimum of 400,000 acres up for potential development. The law says they have to. The only way to stop it would be to change the law, and the political will doesn’t exist for that in Washington.

The good news is while it’s not perfect, this EIS is still better than the original, and offers better alternatives with more restrictions on development. Of the three alternative development scenarios being practically considered by BLM, one (almost) fully protects the Porcupine Caribou Herd’s calving grounds from development.

Moreover lease sales are not the same thing as development in the Arctic Refuge. They don’t just get a piece of paper that says “sure, go ahead and drill here” and start building oil wells the next day–they may buy a lease and never develop it. Likewise, when the first leases were made available, it was with the fewest possible restrictions on development, and even then the industry found them about as appetizing as a wet bologna sandwich and made very few bids. Just because leases are made available doesn’t mean anyone is actually going to buy them. The ultimate hope is that decision makers will choose the most restrictive scenario that best protects the Porcupine Caribou Herd and all the other treasures of refuge, a scenario that is at odds with making developing the Arctic Refuge a good business choice.

This is all… frustrating at best, but the fight isn’t over. There’s still time for action. For one thing, you can actually go and comment on the SEIS. Tell the U.S. government you won’t accept any development in the Arctic Refuge. You can pop over to the CPAWS Yukon website and sign our campaign letter, or you can write your own.

Photo by Ken Madsen.

You can also support the Arctic Refuge and the Porcupine Caribou by talking about the Arctic Refuge; share a post, tell your friends, tweet about it.

A bunch of rich people want to roll into what’s ostensibly a wildlife refuge and start putting holes in the ground where the Porcupine Caribou raise their babies so they can slurp up oil and gas and walk away a little bit richer than they were before.

Does that seem right to you? Does that seem like something that’s good? Do you think it’s possible to have a wildlife refuge remain a refuge if you turn it into an oilfield?

I don’t think that’s even remotely possible, I don’t think that’s right and I don’t think that’s good.

If you don’t either, then say something. The Arctic Refuge needs you too.