Uncategorized

Cyanide in the Environment: A webinar on the Eagle Mine disaster

Cyanide in the Environment

A webinar on the Eagle Mine disaster

Compiled by Paula Gomez Villalba | March 31, 2025

In the wake of the Eagle Mine disaster, Yukon Seed & Restoration hosted a webinar with updates on the disaster response and ongoing risks from the toxic cyanide solution. Mark O’Donoghue, retired Biologist and advisor to the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun, explained the initial heap leach failure and outlined the response so far, including water treatment, storage capacity, groundwater contamination, and ongoing monitoring. Cyanide, cobalt and mercury are three major contaminants of concern. Dr. Laurie Chan, Canada Research Chair in Toxicology and Environmental Health and University of Ottawa professor, spoke about their chemistry, toxicity, and environmental health risks. These conversations are especially important as the Eagle Mine disaster continues to unfold, with toxic water still seeping into the land.

Mark O’Donoghue on Eagle Mine

“It’s been damage control and it’s been triage… This is all happening very quickly. The emphasis has been on avoiding a catastrophe… If nothing was done to contain the water, we would have had a surface spill of cyanide water and that could still be the case because their ponds are quite full there. It would flow from the creek and the toxins out there would have certainly killed everything down the McQuesten River and it would likely have done so down part of the Stewart River as well.”

“There’s massive contamination that’s gone into the groundwater, both in terms of when it first slid and now it’s been leaking since then… But it is estimated that there’s several hundred thousand cubic meters of contaminated solution in the groundwater. So that’s several hundred million liters. It’s a huge amount of contaminated groundwater in the lower Dublin Gulch area.”

“The plume of contaminated groundwater from the mine site has reached Haggart Creek and is having an increasing effect on water quality in the creek. There’s lots of uncertainties about where the water’s going and whether it’s even reasonable to intercept it.”

“Haggart Creek has huge value biologically and culturally. It’s known as a salmon-spawning stream and a salmon-rearing stream. It also has a hugely important grayling run. This is the most important grayling fishery in the Na-Cho Nyäk Dun traditional territory, right where the Haggart Creek comes into the South McQuesten River. The grayling congregate there in March/April, and people go there and fish through the ice. It is a big community event every year.”

“One of the big problems is that [Victoria Gold’s] water treatment plant was never designed to take cyanide out. It was designed to deal with other water that’s coming out of the mine area where they’re mining [with] high turbidity, other metals in it. This water treatment plant had to be repurposed and basically jury-rigged to try and make it so it could remove the cyanide. Getting this right has taken a lot longer than I expected.”

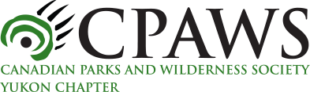

“Each of these dots is a different water monitoring station within the first four kilometers south of where Dublin Gulch flows into the creek. Water quality stayed quite safe all the way through September and then cyanide started increasing and has increased pretty steadily since then… That’s the case with some other contaminants.

— Mark O’Donoghue with the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun

Dr Laurie Chan on Cyanide

“It’s fairly uncommon to have high levels of cyanide in the environment so there is relatively few data and very few studies looking at the impact of cyanide in the environment.”

“Cyanide is a very well-known poison. It’s very toxic, but at low doses, our bodies can handle it. Moose and caribou, all animals have some capacity to detoxify the cyanide and then excrete it. It doesn’t stay in the body for long. It doesn’t bioaccumulate in the body.”

“Cyanide in water does not bioaccumulate in tissues or fish because it gets transformed and released. [When] eating fish the risk of contaminative cyanide is low… If there’s a dead fish, there may be some residual cyanide in the fish, but if the fish is alive and kicking, it shouldn’t be a major risk of cyanide.”

“Fish and plankton, those little animals or plants that fish eat, are very sensitive to cyanide…The Canadian drinking water guideline is 0.2 milligram per litre. The guideline for fish is .005 milligram per litre. So, humans are more resistant to cyanide than fish.”

“Cyanide actually inhibits respiration in the cell and it doesn’t discriminate what cell. So that’s why cyanide has got systemic toxicity. It affects the whole body.”

“We get cyanide usually through breathing in, eating, drinking water, or even contacts from skin absorption. The concern is not just ingesting water. If the creek or the river is contaminated, if kids are swimming there, then we need to worry about thermal absorption as a route as well, not just drinking.”

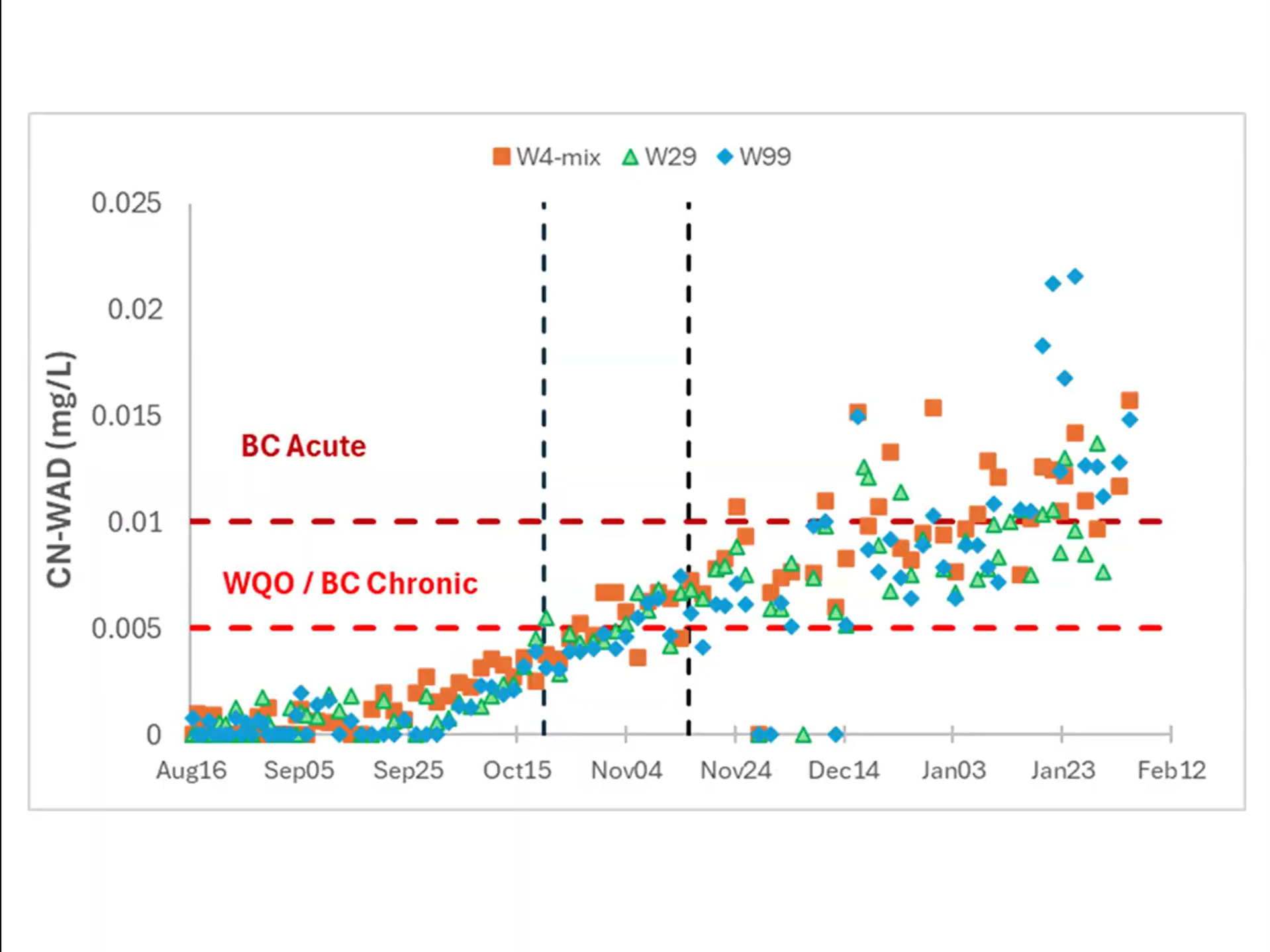

Dr Laurie Chan on Other Contaminants

“Organic mercury can bioaccumulate unlike cyanide and cobalt. It will accumulate in the body of fish and animals. The bigger the fish is and the older the fish is, the more mercury it will have in the body… Mercury attacks the brain and the heart… If there’s consistent release of mercury in the environment, the sediment will have high levels of mercury in the river or the creek, and if there is the right bacteria it will become organic mercury that goes into fish. The fish will have high mercury and not be fit for human consumption. It’s a long-term effect, the mercury doesn’t go away easily.”

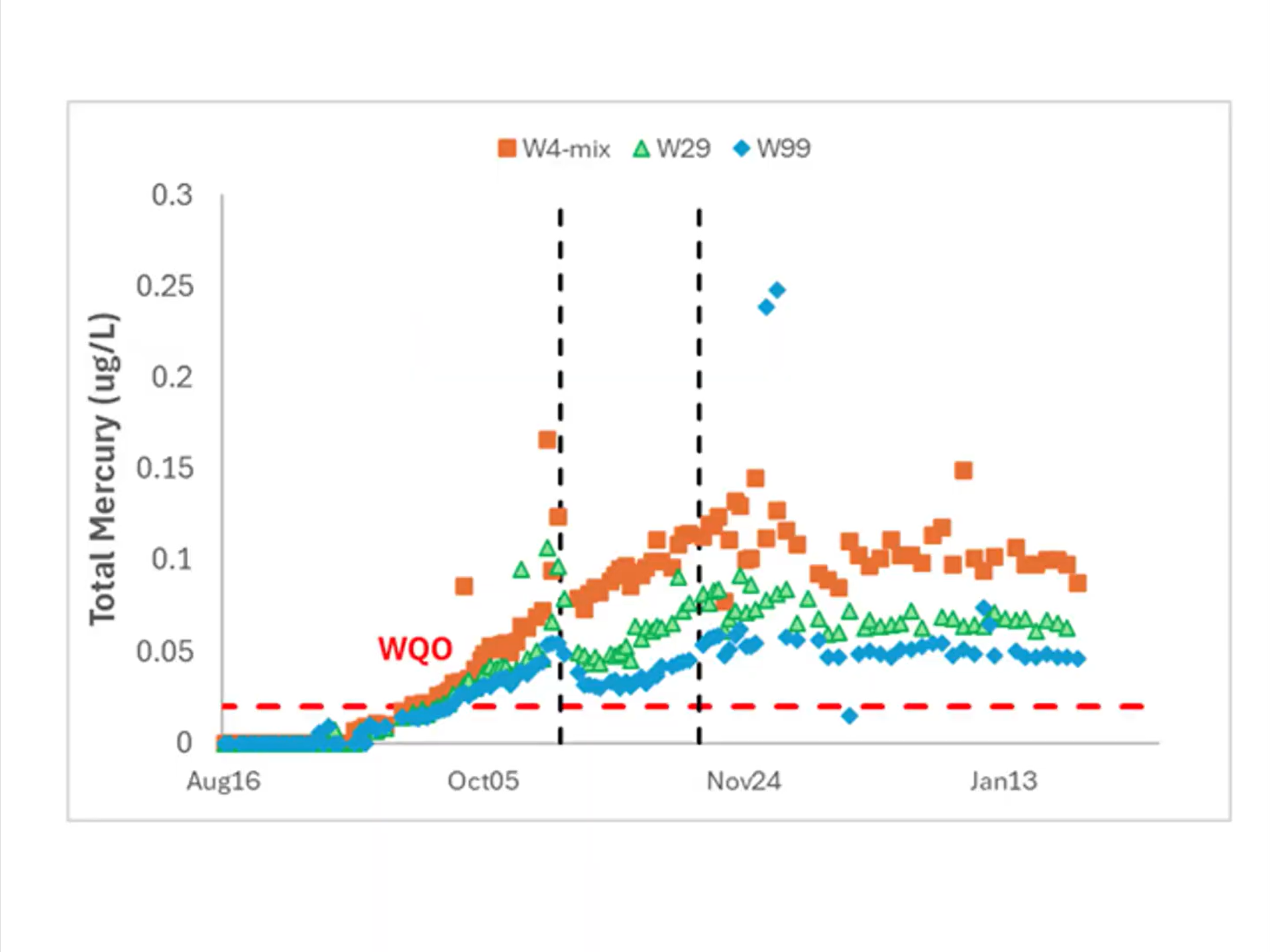

“Cobalt is 50 times less toxic than cyanide. Since it’s a nutrient and not very toxic, we don’t have any drinking water guidelines for cobalt. But in the environment, cobalt released in soil, water, plants and cannot be created or destroyed. Cobalt in water has two different forms, one that binds to particles and one that dissolves. The dissolved cobalt is more bioavailable and toxic.”

“We are still in the early stage of understanding what are the impacts of these chemicals in the environment and to people in the area. So we need, definitely, more monitoring…and then we need to do risk assessment, looking at this information and having a better understanding of what do people use, where do people hang out to actually estimate the dose, to answer the question of what might be the effects.”

There’s a lot of fear and uncertainty surrounding the Eagle Mine disaster and the decades of cleanup ahead. The impacts aren’t just technical, they’re deeply personal too. This disaster will continue to affect life-sustaining waters and how people connect with the land. It threatens health, culture, and future generations—but this isn’t something we simply have to accept. There are ways to push for accountability, protect communities, and stand in solidarity with the First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun.

“Go to the emergency response webpage and fill out the letter to send to your local MP/MLA demanding that we get a public inquiry on this so we get to the bottom of it and it never happens again. ”

— Chief Dawna Hope, First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun

The webinar was hosted by Yukon Seed and Restoration on Monday, March 10th, 2025 with in-person showings at Ihdzí’ in Mayo and the NNDDC office in Whitehorse, Yukon. Quotes edited for length and clarity. The full webinar recording can be found here.

Yukon court dismisses case that threatened the Peel Plan

Written by Joti Overduin, rally photos by Adil Darvesh | March 13, 2025

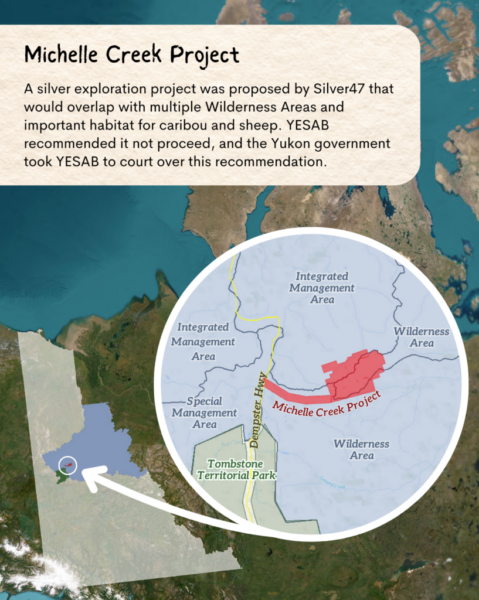

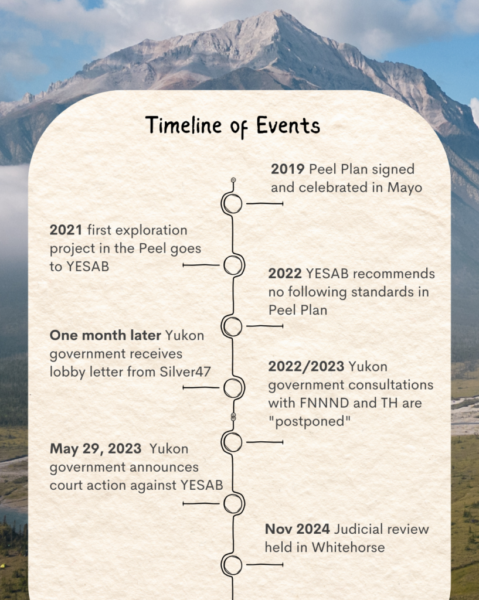

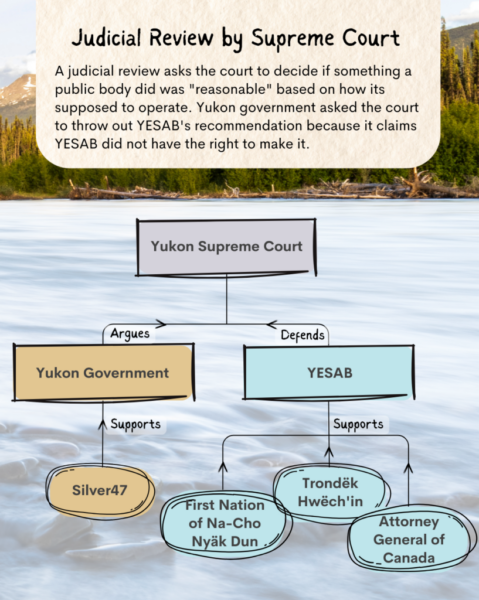

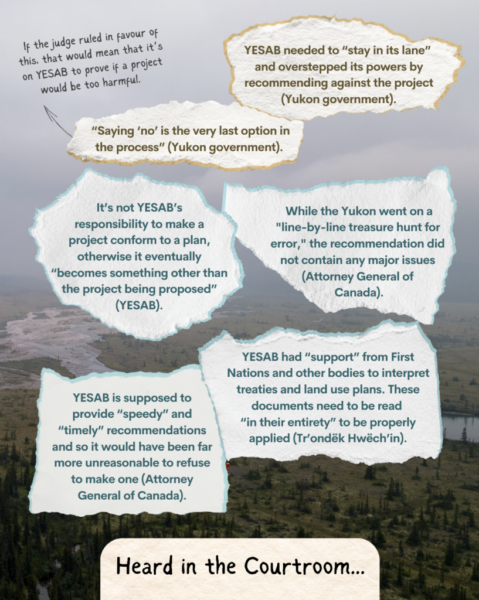

After rallying together in the cold in Whitehorse and across the Yukon and NWT last November, the ruling from the judge to dismiss the Yukon government’s case was very much welcome. It was a decision that reflected the reactions of many from the outset of this confusing and disappointing court action on YESAB’s recommendation that the Michelle Creek mining project not proceed.

The Yukon Supreme Court judge determined that bringing this court action forward was both not legally permissible, and out of step with the constitutionally protected process. The judge didn’t touch on the specifics of the YESAB recommendation or how YESAB went about creating it, as that is meant to be discussed between the Yukon government, Trondëk Hwëch’in, and the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun.

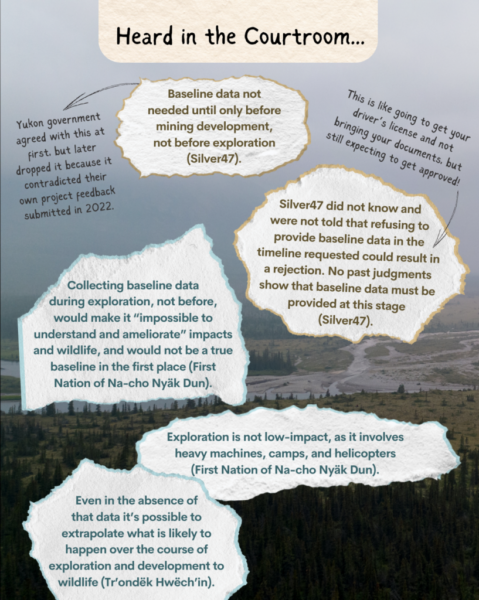

At CPAWS Yukon we all shared feelings of deep gratitude to Trondëk Hwëch’in and the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun for all the energy, time, and work dedicated to defending the integrity of the Peel Plan and the Final Agreements. There was also a strong focus on the importance of baseline data (information about an area before exploration or mining) to evaluate potential impacts and the effectiveness of mitigation efforts on the land, waters, and wildlife—critical not only for the Peel but for development proposals throughout the Yukon.

Peel Watershed court case update from December 2024. This isn’t a comprehensive summary of the court proceedings, but rather a glimpse into some key points that stood out to us.

Now that the court action has been dismissed, it is time for the Yukon government to go back to the process of consulting Trondëk Hwëch’in and the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun on YESAB’s recommendation for the proposed exploration project. We remain curious and hopeful that the Yukon government will work together with both First Nations to ensure the Peel Plan is upheld, and that it follows YESAB’s thorough recommendation that this first application to develop in the Peel not go ahead. We must ensure that development in the Peel and throughout the Yukon is done in a way the reflects not just the needs of our generation, but many generations from now too.

“It took many years of work and many court challenges before the Peel Plan was finally approved, and yesterday’s Court decision builds on the significant effort of Yukon First Nations and all Yukoners to ensure that the Peel Plan is properly and honourably implemented. This is a win for TH and for land use planning under our treaty.”

— Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Deputy Chief Erin McQuaig

“We are pleased to see Chief Justice Duncan rightfully recognize that Yukon’s case was inappropriate and should never have been brought. We hope Yukon will reconsider its approach to the Michelle Creek project and recognize the project should not proceed—as YESAB determined.”

— First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun Chief Dawna Hope

Protect the Peel rally across the Yukon and NWT

- Dawson, YT (photo by Sharon Vittrekwa)

- Whitehorse, YT (photo by Adil Darvesh)

- Tsiigehtchic, NWT (photo by Fredrick Sonny Blake)

- Whitehorse, YT (photo by Adil Darvesh)

- Fort McPherson, NWT (photo by Laura Nerysoo)

- Mayo, YT (photo by Erin Holm)

Panel Discussion: Mining on Unceded Territories

Mining on Unceded Territories

Transformative Mining and Alternatives Panel

As Yukon mineral legislation is being re-written, explore the history and future of mining on unceded Indigenous Lands in the Yukon.

This panel was held on March 6th, 2025 as part of a series of four public, virtual panels with thinkers and leaders from across the Yukon and beyond to ask: How can we transform mining to ensure disasters such as the Eagle Mine failure never happen again? What are the alternatives to resource economies?

Panelists included Testloa Smith (Kaska Elder), Josh Barichello (Ross River Dena Council Lands Department), Ann Maje Raider (Kaska Elder, Liard Aboriginal Women’s Society), Linda McDonald (Liard First Nation, Liard Aboriginal Women’s Society), and Hammond Dick (Kaska Elder). Moderated by Caitlynn Beckett (Memorial University) and Jared Gonet (Yukon University).

“Our land, we say, is unceded. It means no treaty, and we still maintain that today. [This] does bring the government to our table. It does bring industry to our table. But they have a process, YESAB, which is legislated to look at how projects are being developed and permitted to become a mine. Because of the time they have slotted to do their assessment there seems to be a big gap [in] what our nation understands about the land, about the animals, about the water, and about all the plants. Traditional knowledge has to be incorporated into these discussions. They’ve tried to, but still they’re not getting [it in] the ways that we wanted to see.”

— Testloa Smith, Kaska Elder

“Back in 2014, the Kaska Nation challenged Yukon government’s free entry into their mining claims and the claims [that] were staked by exploration companies without consultation, because it was adversely affecting aboriginal rights and titles and interests. To date, we’re pushing hard to make sure that any mining companies that have an interest in setting up shop in our traditional territory [are] going to be faced with that prospect of consultation and accommodation. We’re out there, and we’re quite observant about what’s going on.”

— Hammond Dick, Kaska Elder

“For the most part [the people who are there developing the land], they’re from all over the world, or from other parts of the world, whereas Kaska people and other people are living there. The word Kēyeh, for example, I believe comes from the word ‘foot’ or ‘boot’. We’ve walked on the land, we know the land, our ancestors knew the land, and that’s the relationship to the land. There’s a huge difference just in the perspective and the respect for the land.”

— Linda McDonald, Liard First Nation, Liard Aboriginal Women’s Society

“If you’re being compensated for something, is that, in a way, just an easy way for the mining companies and governments to [get] a green light to do the damage in the first place… How are you going to compensate for a caribou herd? What kind of dollar figure are you going to put on that?”

— Linda McDonald, Liard First Nation, Liard Aboriginal Women’s Society

“The mining companies and legislation do not allow looking at the gender-based analysis when it comes to mining and looking at perpetrators of violence coming into these mining camps. What’s not factored in YESAB is the cultural relevance, the social relevance of mining, what happens to our community, the addictions. None of that is factored. It’s time we look at YESAB and we look at mining legislation that really does protect our lands and our rights to the land.”

— Ann Maje Raider, Kaska Elder, Liard Aboriginal Women’s Society

“I think what has been happening in our territory is that they’ve been stomping on our aboriginal rights and title because they know we don’t have the money. They come and stomp more, [like] the most recent decision with a mine in our backyard. You know our people are saying no. But they don’t want to listen because it means money in the back pockets of government… Our people still live in poverty. The mines come and go, and who’s left with the toxins? We are. Our land is precious to us as it was to our ancestors, but they don’t want to hear [that], so our only recourse is always courts.”

— Ann Maje Raider, Kaska Elder, Liard Aboriginal Women’s Society

“When I listen to many stories of what happened during the land claims discussions, [there’s] rationale for that powerful decision that Kaska made. There were many reasons, but one thing that I hear again and again, is that dividing the land, putting boundaries and borders, and treating different lands differently, was a challenging thing to reconcile for those elders who had a responsibility to all of their territory, to all of their land. Cede, release, and surrender became part of crown lands, the lands that were not chosen to be settlement lands, [and that] was hard to reconcile.”

— Josh Barichello, Ross River Dena Council Lands Department

“They have applications to go and make their trail, to go and drill further on the same area as the [proposed BMC mine]. Now we say the same thing as [with] the mine. We say we got concerns about the caribou, about the water, about our plants, and our gophers, our small animals that we harvest. Yet [they] say you guys are talking about mine permitting, we’re talking about drilling. But it’s the same area, the same concept, the same thing. That’s what really frustrates us. That’s why you hear about colonialism, of things that they try to separate… Our people understand water goes out past the footprint; the animals go past the footprint of the mine.”

— Testloa Smith, Kaska Elder

“The Lands Department, especially in the context without a final agreement, are so underfunded and don’t have the mechanisms that came from the UFA to really get involved in the same way, and so everybody else sort of has a leg up in terms of their ability to engage. At the same time, we’ve been bombarded, absolutely suffocated with all these outside interests. If you look at a map of mineral claims in the Ross River part of the Kaska Nation, I think it’s about 16% of the area has been staked, the rocks have been given away with no treaty on unceded land, with no Kaska consent, or very little consultation in many cases.”

— Josh Barichello, Ross River Dena Council Lands Department

Supported by CPAWS Yukon, To Swim and Speak with Salmon, and Research from the Front Lines. Organized by Jared Gonet (Faculty in Indigenous Governance and Science at Yukon University and PhD candidate at University of Alberta), Caitlynn Beckett (PhD Candidate at Memorial University), and Krystal Isbister (PhD candidate at University of Alberta and Yukon University); all of whom do research on mining or land relations in the Yukon.

Quotes edited for length and clarity.

Other panels in the series

What the Heap? Understanding the cyanide disaster at Eagle Mine

What the Heap?

Understanding the cyanide disaster at Eagle Mine

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba and Nicole Schafenacker | March 7, 2025

On June 24, 2024, the heap leach at Victoria’s Gold’s Eagle Mine near Mayo, Yukon, on the traditional territory of the First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun (FNNND), failed, causing a slide that released 300,000 cubic meters of cyanide-contaminated water into the ecosystem.

The cycle that kept hundreds of millions of litres of toxic solution contained broke.

Victoria Gold was unprepared for the crisis, and in the months following the disaster failed to take adequate steps to mitigate the damage, while their financial prospects tanked. Late last summer a court put Victoria Gold into receivership, transferring control of the mine site and the company’s finances to more competent hands. Still, there are huge challenges to overcome, like containing the contaminated water, keeping storage ponds from leaking and overflowing, and stabilizing what remains of the heap leach.

This disaster is yet the latest example showing the Yukon is far behind when it comes to responsible mining. A public inquiry can help us change that. We must understand what policies, decisions, and actions from government and Victoria Gold management led to this disaster.

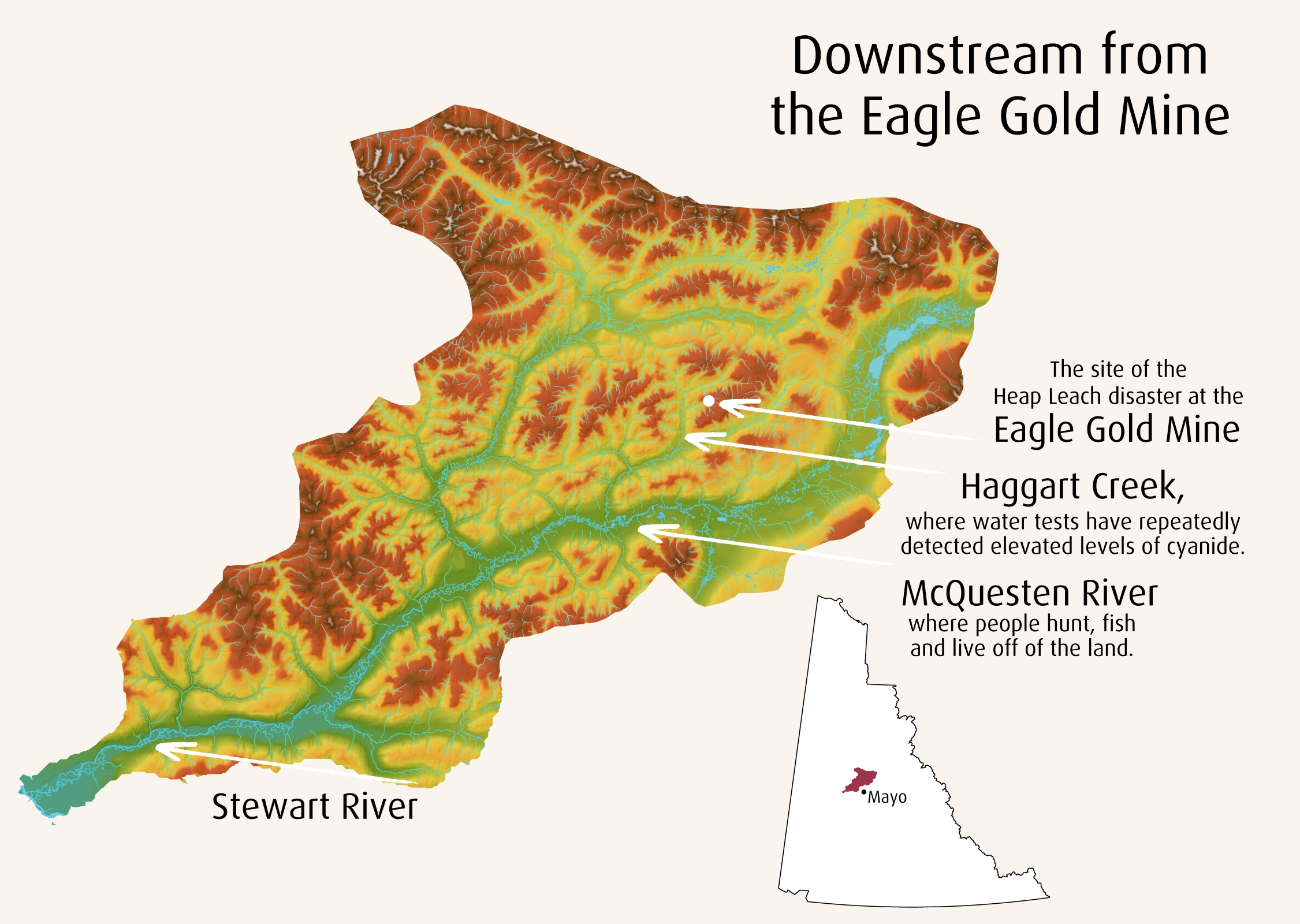

Water contaminated with cyanide and heavy metals is still seeping into the ground. It has reached local waterways, including Haggart Creek in the South McQuesten watershed, home to grayling, and Yukon River Salmon.

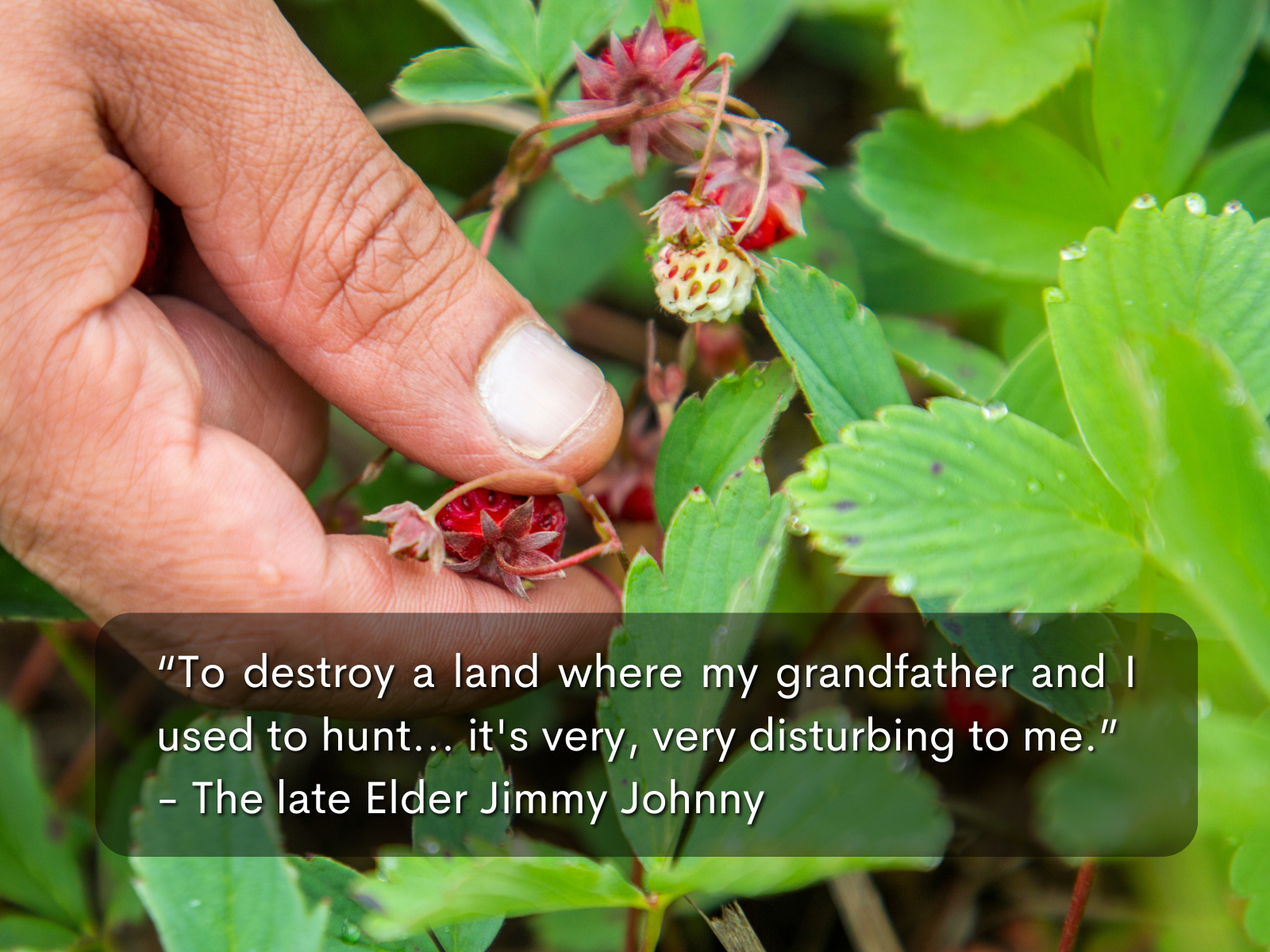

Here, in the South McQuesten River watershed, people fish, hunt, and pick berries. Moose and grizzly bears care for their young, and thousands of birds find refuge during migration. There is no doubt that this disaster will change how people interact with the area.

Quotes from CBC News feature by Julien Greene highlighting people who live near the Eagle Mine Disaster site: Troubled water.

-

In the disaster, the mine’s heap leach facility, a huge pile of rock over which cyanide solution is cycled to extract gold from the ore, failed. The resulting slide and damage to the facility released over 300,000 cubic metres of cyanide-contaminated water into the ecosystem. A month after the initial failure, the territorial government stepped in to begin groundwater interception, and later a full response coordinated by the territorial government with the FNNND emergency response team and federal government.

Even now, eight months later, cyanide is still infiltrating into the environment, with leaks recently reported from a ruptured pipe and from a storage pond meant to contain contaminated water.

Victoria Gold, the owner of Eagle Mine, had a history of violations, unrealized plans, and broken promises, and repeatedly failing to follow the requirements of their operating licenses or meet deadlines to bring the site into compliance. Mining failures like this should never happen again.

“Yukon Government has a lax approach to permitting, compliance, monitoring, and enforcement of mineral activity in the Yukon, and this approach was reflected in YG’s oversight-or lack thereof-of the Eagle Gold Mine… [including] allowing Victoria Gold Corp to operate the Heap Leach Facility without proven cyanide treatment capacity, contrary to the conditions of its Water Use Licence” — First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun letter to the Auditor General of Canada

There are a lot of questions unanswered, and a public inquiry is the only way forward to give the South McQuesten watershed the justice and respect it deserves. Tell Yukon government there must be a public inquiry.

Map of the McQuesten River (Et’o Nyäk Tagé in Northern Tutchone) Watershed

Op-Ed: Unsteady ownership made Minto a disaster waiting to happen

Written by Malkolm Boothroyd | August 6, 2023

Photo from Google Earth, Minto Mine and Yukon River.

Read the full editorial as published in the Yukon News on August 6th, 2023.

—

Unsteady ownership made Minto a disaster waiting to happen

This spring the Minto Mine shuttered, leaving dozens out of work and tens of millions in unpaid bills and royalties.

The Yukon public is on the hook for much of the clean up costs. Many explanations have been offered up for the financial struggles that ultimately sunk Minto.

People have blamed volatile copper prices, the pandemic and spring snowmelt straining the mine’s capacity to treat water. One contractor suggested investors were scared off when the Yukon government requested a higher security bond from Minto. Minto may have been the victim of volatile circumstances, but mining is a volatile business. One study found that around the world, as many as three quarters of mines close unexpectedly or prematurely.

There is a simple explanation for what went wrong at Minto. The company that bought Minto had no business owning a major mining operation and the territory’s outdated mining laws could do little to safeguard the Yukon against the inevitable collapse.

The Minto mine got a new owner in 2019. At the time of the sale, Minto had been operating for over a decade and was nearing the end of its life. Still, the mine was in reasonably safe hands, as far as covering environmental costs went. Back then, Minto was owned by Capstone Mining Corp. Today, Capstone is valued at nearly $4.5 billion, putting it among the world’s 100 wealthiest mining companies. Capstone certainly had the financial resources to care for Minto. It could have implemented the mine’s clean up and closure plan, and the Yukon public wouldn’t have had to foot the bill. Instead, the company chose to sell Minto. As Capstone wrote in annual reports, it sought “value maximizing alternatives” for Minto, and for the company to have “no further obligation with respect to the closure” of the mine.

Capstone found a buyer in UK-based Pembridge Resources. The two companies could not have been more dissimilar. At the time of the sale, Capstone was a fully fledged mining company that also operated mines in the US, Mexico and Chile. Pembridge had never operated a mine before.

Pembridge got off to a rough start. The company’s initial attempt to purchase Minto collapsed after the company failed to raise enough capital. Pembridge was eventually forced to take millions of loans from American hedge funds, in return giving up ownership of nearly 90 per cent of Minto. A Pembridge subsidiary, Minto Metals Corp subsequently took control of the mine.

Minto restarted production in 2019, but without functional water treatment facilities. Contaminated water steadily accumulated, while the mine’s water storage capacity shrunk, eventually falling below the minimum levels required by its water license. In 2022, due in large part to water treatment issues, the Yukon government requested an additional $18 million in financial security, which Minto failed to pay. That same year, Minto announced it would invest $8 million in water treatment, but was unable to resolve its water crisis. This spring Minto Metals’ Board of Directors resigned and the company abandoned Minto.

Still, not everyone lost out as a result of this mess. Pembridge’s CEO earned the equivalent of $1.5 million Canadian dollars the year of the Minto sale. Capstone sold Minto for $20 million US and got to walk away from the mine.

Just six years after Yukon Zinc walked away from the Wolverine Mine, the Yukon has been saddled with another abandoned mine to care for. There are parallels between Minto and Wolverine — both allowed too much contaminated water to pile up, both were plagued by financial hardships and both failed to pay tens of millions in financial security to the Yukon government. A report by the accounting giant PWC detailed what went wrong at Wolverine, parts of which could be cut and pasted into a report about Minto. For example, PWC wrote that Yukon Zinc was a small, risky company, whose profits were vulnerable to changes in metal prices. Yukon Zinc “allowed liabilities to increase at the site, a decision that was influenced by their financial difficulties.” According to PWC, the Yukon government was unaware of many of the financial troubles at Yukon Zinc. The firm wrote that the Yukon should be conducting comprehensive risk assessments of mining companies before granting them licenses.

The Yukon government wanted to see Minto’s life extended, even if it meant a more fragile company taking control of the mine. After Pembridge’s first attempt to purchase Minto fell through, the then premier told the legislative assembly that his government was “hoping that [Capstone] can strike a deal with Pembridge.”

Five years later, the public is responsible for cleaning up Minto. Many red flags might have appeared had there been a risk assessment on Pembridge Resources prior to the sale of Minto. Unfortunately, as currently written, the Yukon’s mining laws don’t require checking to see if a company is a financial disaster waiting to happen.

Hopefully the Yukon government’s lawyers are figuring out if Capstone, or any of the American hedge funds that bankrolled the Minto purchase, can be held accountable for some of the clean up costs. At the same time, the Yukon should make sure that this can’t happen again. The Yukon is in the midst of rewriting its archaic mining laws and new legislation should prevent risky companies from undertaking massive environmental liabilities. Before issuing permits, the Yukon government should assess the financial stability of the companies responsible. Mining companies with moderate financial risk should be required to post higher security in advance. Corporations with high financial risk should not get permits unless they can find more robust companies to guarantee their projects.

Money, of course, is only one dimension of mining. It’s impossible to put a price on salmon runs, healthy caribou herds or the connections that people hold with the land and water. Minto’s financial story is easier to work out, but we have to learn the right lessons from it. Some will try to paint Minto’s downfall as the result of exceptional circumstances. The truth is mines fail all the time. Companies like Pembridge shouldn’t be trusted to oversee massive environmental risks if they can’t withstand a couple of rough years. It’s time to update our mining laws to help ensure that more mines don’t end up in the hands of volatile companies.

Mining 101: Digging into the terms

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba, Communications Coordinator. Photos by Makolm Boothroyd.

April 6, 2023

Across much of the Yukon, boreal forests and wetlands stretch as far as the eye can see, crisscrossed by ancestral rivers that provide for the land, people, and wildlife. Threatening these rich wild spaces is the legacy of the Klondike Gold Rush, which lives on in the territory’s mining laws. These laws date back to the 1900s and prioritize short-term gains, reflecting the extractive history of colonialism on Indigenous land.

Now the Yukon government is creating a new minerals legislation, in collaboration with Yukon and Transboundary First Nations. The new mining legislation will cover the entire life of placer and quartz/hardrock mines, from prospecting to production to closure.

This is a once in a generation opportunity, so we want to make it as accessible as possible for you to share your vision for mining in the Yukon. Even if you’re not a mining expert, you’re an expert on your hopes and vision for the territory’s future. Mining has shaped and will continue to shape the Yukon, and this legislation needs to prioritize the territory’s long-term health and prosperity.

There are lots of terms, synonyms, and potential approaches related to mineral development. Here we’ll define some common mining terms you might come across. Once you’re ready to take action, check out our guide to completing the official survey. Responses will be used by the Yukon government as they continue developing the legislation.

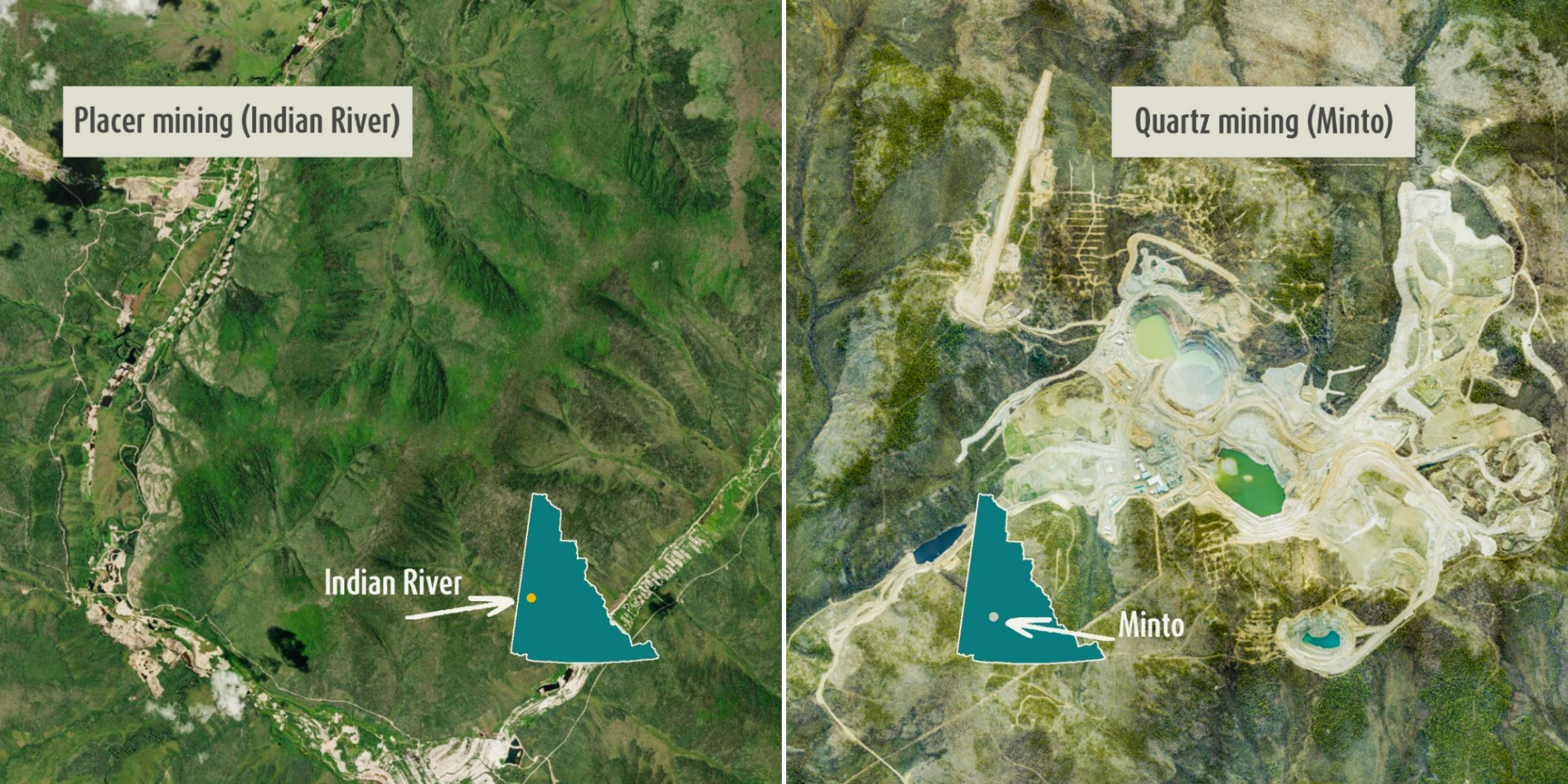

Placer Mining: Placer mining is a way of extracting minerals (usually gold) that has settled in the bottom of water courses like rivers, creeks, and wetlands.

These minerals often lie beneath frozen layers of soil and gravel requiring miners to use excavators, bulldozers, and pressurized water to strip away vegetation, soil, and let the permafrost thaw.

Quartz/Hardrock Mining: Hardrock mining is where mining companies extract minerals from bedrock veins using large open pit or underground mines.

Extracting minerals from the rock often involves the use of chemicals that can be harmful if released.

Images from Google Earth. Graphic by Malkolm Boothroyd.

Prospect of profit, or automatic land rights?

Free Entry System: Free entry grants any individual or company the right to stake a mining claim without the need for a permit or other authorization.

Mineral rights are automatically approved without consultation or consent from First Nations. These mining claims then hold tremendous leverage over land use planning decisions.

Acquisition: Rules about who can stake a claim and how.

Currently any adult can do so by pounding a few stakes into the ground and paying a $10 fee. Part of the free entry system.

Disposition: Rules for where mineral staking can happen and what mineral rights are granted.

Prospectors can stake a claim anywhere, unless the area has been withdrawn from staking (like designated protected areas). Part of the free entry system.

Mineral Tenure/Mining Claim: When an individual or company has tenure or a claim, they hold the rights to explore and develop minerals below the claim.

These are acquired through the free entry system and have to be maintained in good standing.

Exploration: Evaluating the mining potential of an area where a company has mining claims.

Exploration can involve building roads and cutting trails, disturbing wildlife with daily flights, building camps, and moving tens of thousands of tonnes of rock. Claim holders automatically have the right to explore, but specific exploration projects are subject to approval.

Mining roads cover Arch Mountain in the Kluane Wildlife Sanctuary.

Accounting for harm and public benefits

Financial Security: Hardrock (and a few placer) mining companies provide financial security to cover the costs of reclaiming and closing their mine site in case they abandon it.

This security amount is paid before production begins and reassessed every 2 years. The Yukon has a long track record of underestimating security needed, leading to expensive taxpayer funded cleanups and environmental harm left unsecured.

Royalties: Royalties are payments made to governments by mining companies, recognizing that the public and First Nations own the rights to minerals and should benefit from their extraction.

Placer miners currently pay just 37.5¢ per ounce of gold (the same rate as the early 1900s) and quartz miners are only required to make payments once they start making a profit.

Tailings: Tailings are waste materials left over after mining and can include harmful chemicals and metals.

Hardrock tailings are left in large ponds or are sometimes dried and stacked. Reclaiming tailings is a challenging task and some tailings will require treatment indefinitely.

Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board (YESAB): YESAB is responsible for reviewing proposed mining projects, and recommending mitigations and whether or not a project should go ahead to the Yukon government.

The YESAB process is separate from the new mining legislation but links very closely to it.

Abandoned Wellgreen quartz mine, clean-up costs are an estimated $15 million.

A changed landscape

Reclamation: Reclamation involves transitioning land to a different state after exploration and mining ends.

It’s usually impossible to fully restore the original ecosystem – simply too much has changed. The result is a different landscape where original values have been restored, replaced, or lost to different extents. Reclamation can involve filling in pits, recontouring the landscape, and planting vegetation. It’s expensive and hard to enforce, sometimes resulting in mines being abandoned.

Peat: Peat is a carbon-rich soil found in some wetlands that takes thousands of years to form.

Peatlands are vulnerable to placer mining because gold settles at the bottom or rivers and wetlands. When excavated, the peat decays and releases massive amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. Peatlands cannot be restored.

Permafrost: Permafrost is frozen soil that holds huge stores of greenhouse gasses like methane and carbon dioxide.

Typically we would say that permafrost is soil that is frozen year-round, but climate change and developments like mining are causing permafrost thaw.

Closure: The goal of mine closure is to return the site to a stable, non-polluting state and to meet reclamation goals.

This process takes many years. In the Yukon, a hardrock mine is considered closed when a Closure Certificate has been issued. Despite the number of mines that have operated in the territory, none have received this certificate.

Abandonment: When a mining company leaves a site without meeting the proper reclamation or closure measures.

Abandoned mines can pose significant risks to people and the environment, as contaminants and equipment are left unchecked. Reclamation and closure is then handled by the Yukon government with public funds.

The stages of placer mining show how in spite of the best reclamation efforts, natural peatlands can’t be restored.

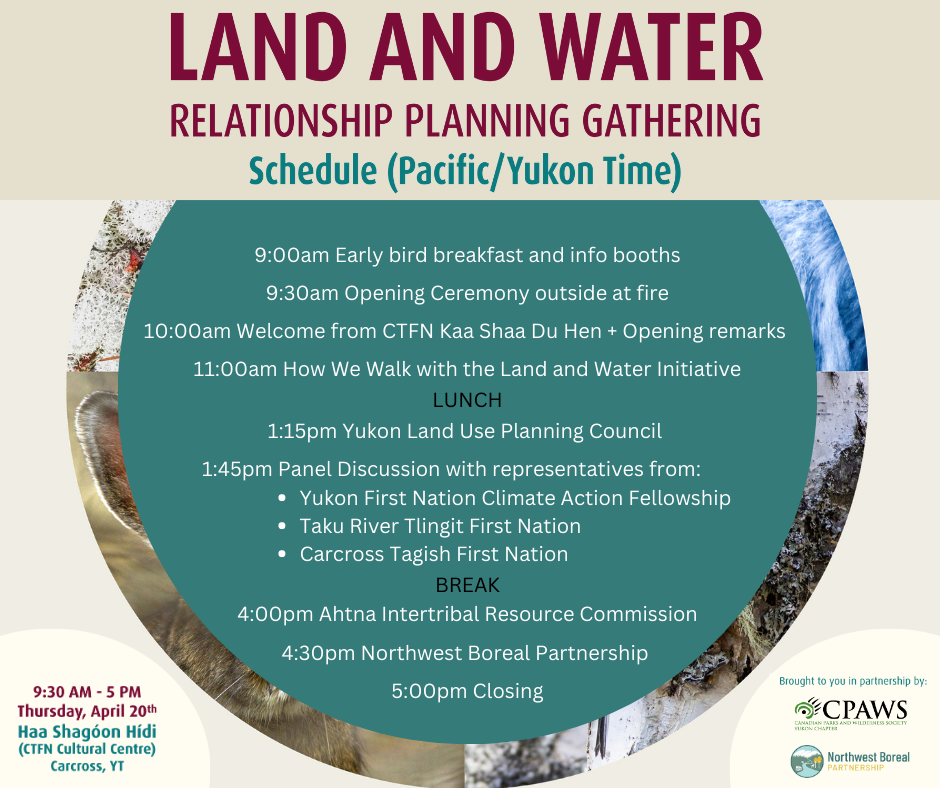

Land and Water Relationship Planning Gathering

Event Details

- Thursday Apr 20, 2023

- Open at 9am, Official start at 9:30am, and Closing at 5pm.

- Location: Carcross, Yukon (70km from Whitehorse)

- Venue: Haa Shagóon Hídi (Our Ancestors House – Carcross Tagish First Nation) in the Main Hall and Firepit area + Virtual Interactive Livestream via Gúnta Business

- Lunch + early bird-breakfast, coffee, tea and afternoon snack provided

- Registration required so we can ensure we have enough food, and to be able send out the Zoom link for those attending virtually

Speakers attending:

- Yukon First Nation Climate Action Fellowship

- How We Walk with the Land and Water

- Taku River Tlingit First Nation

- Northwest Boreal Partnership

- Carcross/Tagish First Nation

- Ahtna Intertribal Resource Commission

- Yukon Land Use Planning Council

Organized by CPAWS Yukon and the Northwest Boreal Partnership, this gathering is bringing people together to listen, share and learn about the intersection of efforts and opportunities around land and water planning, climate adaptation, conservation, and regenerative economies – with a highlighted focus on Indigenous-led and collaborative efforts.

We expect to bring together a diverse group of representatives from First Nation communities and governments, government agencies, funding groups, academic institutions, conservation groups, the tourism and business sector, and land planning and management organizations.

In addition to teaching and inspiring one another with examples of what is possible, we hope this gathering will help everyone work together on future land-water initiatives and planning in the North, across the nation, and cross-borders.

This all-day event will include lunch, snacks, and food for thought as we listen and learn together, and share thoughts on Indigenous-led stewardship initiatives, land and water relationship planning, regenerative economies, First Nation climate solutions, and cross-border initiatives.

Options for Attending

In-person:

Doors open at 9:00am for an early-bird breakfast and the event will begin at 9:30am. We aim to wrap up the event at 5pm. Please dress to be outdoors for portions of the day.

Driving Directions from Whitehorse: Drive East on the Alaskan Highway (1), turn right on the Klondike Highway (2 Southbound) following signs to Carcross. After 51.5km, Haa Shagóon Hídi will be on the left hand side of the highway. Expect it to take about 60 minutes to drive from Whitehorse.

*If transportation from Whitehorse is a barrier for you, please let us know so that we can assist you in joining the gathering. Email cdow@cpawsyukon.org

Virtual:

This is more than simply watching via zoom. This gathering is an interactive hybrid event, made possible by Gúnta Business. Gúnta business specializes in high-quality and highly interactive live-streaming, making these important community events accessible to all.

Where to begin?

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba

Updated December 2022

Every year there are many opportunities to connect with nature, but getting started isn’t always so easy. Our forests and lands are home to many plants, animals, and a long history of how Indigenous peoples cared for and used them. We’re all learning— whether it’s names of plants budding after a long winter, or a new exciting way to stay active in the mountains.

This list highlights a few resources and spaces around the Yukon that we’ve found helpful in fostering connections with our wild spaces.

Learn

The Boreal Herbal: Wild Food and Medicine Plants of the North

Written by Yukon resident Beverley Gray, this book is an amazing guide to identifying and using plants found in the North. It includes colour photos and profiles on specific plants, many recipes, and instructions on how to preserve plants. Many Yukon public libraries have copies available to borrow.

Government of Yukon Guide to Hunting & Guide to Trapping

These Government of Yukon guides dive into the rules and regulations of harvesting wildlife, how to get licenses, and how to be safe and responsible. They also highlight key education courses and workshops.

Culture

Kwanlin Dün First Nations Justice Department

The Justice Department “delivers cultural recreation, outreach and healing programs and services to youth (ages 12 to 29), their families and caregivers, and the whole community for the purposes of reducing risk factors, revitalizing cultural and traditions and improving quality of life.”

Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre

The Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre is the cultural home of the Kwanlin Dün First Nation in downtown Whitehorse. It is a gathering place that hosts events and workshops, including a hide tanning camp and sewing circle.

Council of Yukon First Nations

The Council of Yukon First Nations offers health, medical, culture and language, recreation, and social support. Their mandate is to serve as a political advocacy organization for Yukon First Nations holding traditional territories, to protect their rights, titles and interests.

Move

Yukon Aboriginal Sport Circle

The Yukon Aboriginal Sport Circle is a non-profit society dedicated to promoting Aboriginal sports and participation. They offer many different sports programs in Yukon communities, including Arctic Sports, Dene Games, and Archery.

Kwanlin Koyotes Ski Club

The Kwanlin Koyotes are a youth ski group based out of the Kwanlin Koyote Cabin in McIntyre Subdivision. Their mandate is to get kids out on the land, learning how to ski, and taking in the natural environment that surrounds us.

Photo by Malkolm Boothroyd.

![Heard in the Courtroom... Consultation was at the “lowest” level of priority, and not needed until only before mining development, not exploration in any case (Yukon government). If this is how the Peel Plan is to be interpreted and applied in the future, it represents “something much less than [we] bargained for” (Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in). The judicial review itself represents a “failure of reconciliation” (First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun). Lawyers cited numerous legal cases which suggested the precedent that provincial and territorial governments do have a treaty obligation to consult before doing something like this (First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun). Note ruling is expected relatively soon, around Feb 2025; stay tuned for more updates! Heard in the Courtroom... Consultation was at the “lowest” level of priority, and not needed until only before mining development, not exploration in any case (Yukon government). If this is how the Peel Plan is to be interpreted and applied in the future, it represents “something much less than [we] bargained for” (Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in). The judicial review itself represents a “failure of reconciliation” (First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun). Lawyers cited numerous legal cases which suggested the precedent that provincial and territorial governments do have a treaty obligation to consult before doing something like this (First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun). Note ruling is expected relatively soon, around Feb 2025; stay tuned for more updates!](https://cpawsyukon.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Michelle-Creek-Court-Case-Update-8-819x1024-479x600.png)