Blog

Mining 101: Digging into the terms

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba, Communications Coordinator. Photos by Makolm Boothroyd.

April 6, 2023

Across much of the Yukon, boreal forests and wetlands stretch as far as the eye can see, crisscrossed by ancestral rivers that provide for the land, people, and wildlife. Threatening these rich wild spaces is the legacy of the Klondike Gold Rush, which lives on in the territory’s mining laws. These laws date back to the 1900s and prioritize short-term gains, reflecting the extractive history of colonialism on Indigenous land.

Now the Yukon government is creating a new minerals legislation, in collaboration with Yukon and Transboundary First Nations. The new mining legislation will cover the entire life of placer and quartz/hardrock mines, from prospecting to production to closure.

This is a once in a generation opportunity, so we want to make it as accessible as possible for you to share your vision for mining in the Yukon. Even if you’re not a mining expert, you’re an expert on your hopes and vision for the territory’s future. Mining has shaped and will continue to shape the Yukon, and this legislation needs to prioritize the territory’s long-term health and prosperity.

There are lots of terms, synonyms, and potential approaches related to mineral development. Here we’ll define some common mining terms you might come across. Once you’re ready to take action, check out our guide to completing the official survey. Responses will be used by the Yukon government as they continue developing the legislation.

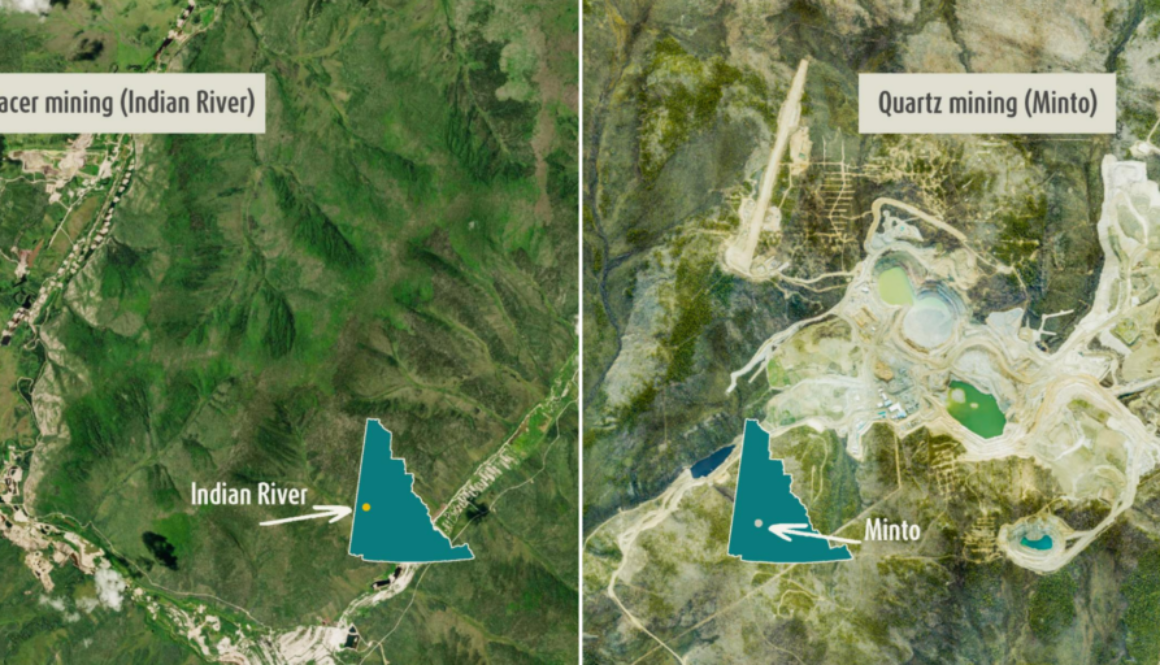

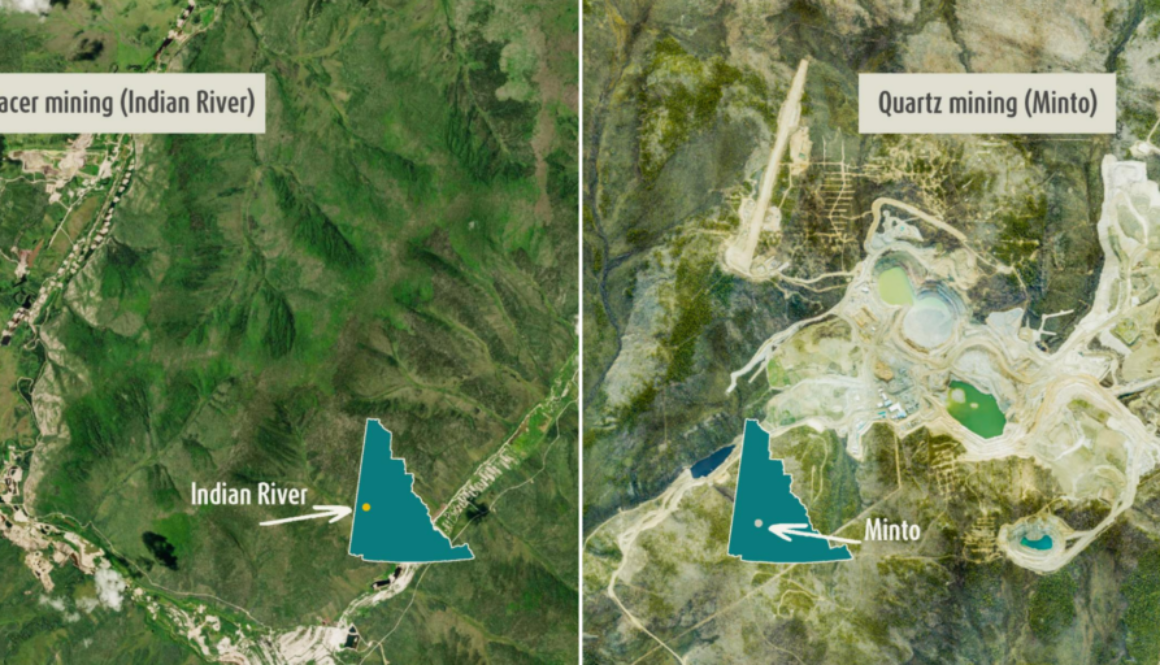

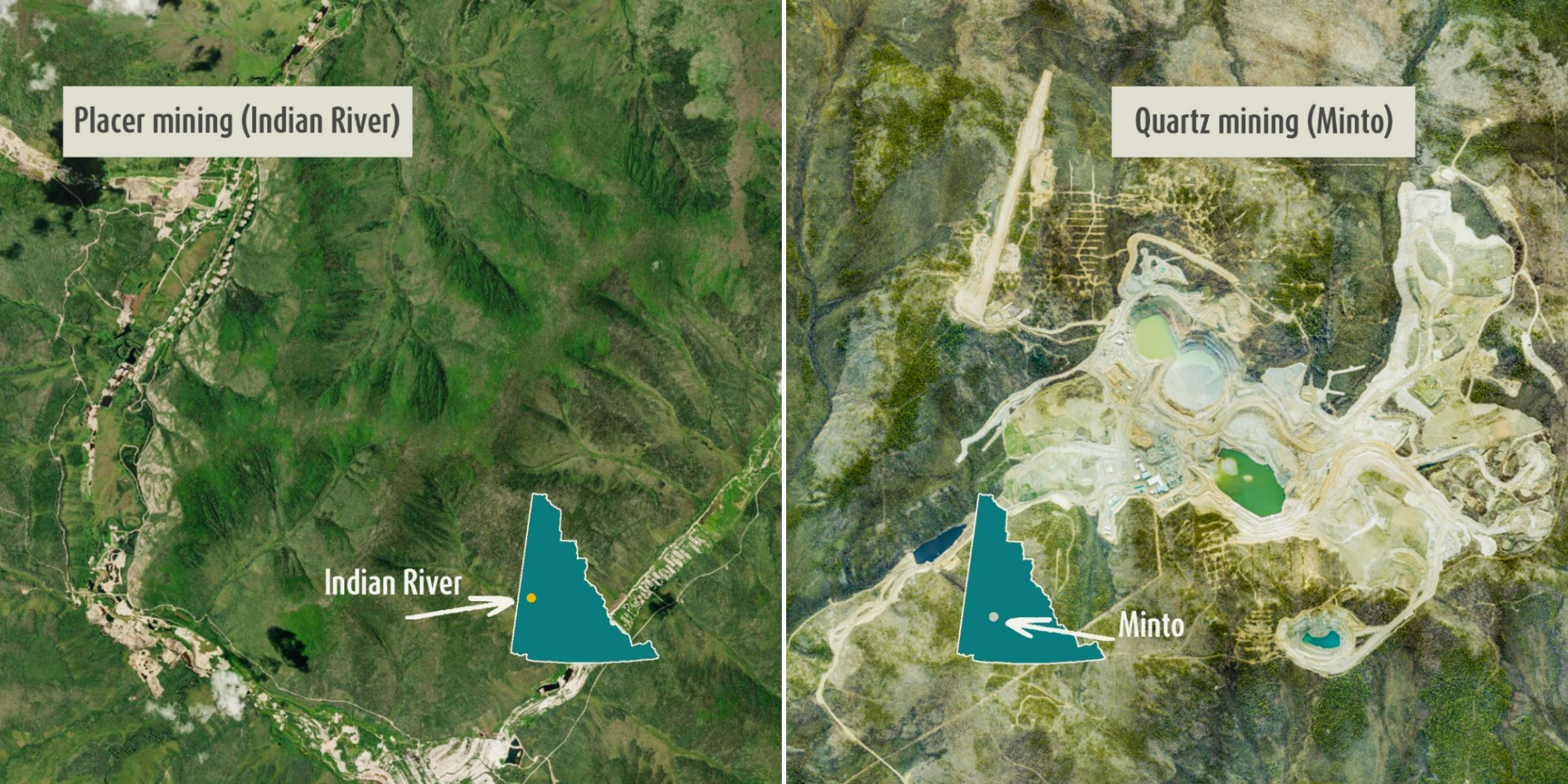

Placer Mining: Placer mining is a way of extracting minerals (usually gold) that has settled in the bottom of water courses like rivers, creeks, and wetlands.

These minerals often lie beneath frozen layers of soil and gravel requiring miners to use excavators, bulldozers, and pressurized water to strip away vegetation, soil, and let the permafrost thaw.

Quartz/Hardrock Mining: Hardrock mining is where mining companies extract minerals from bedrock veins using large open pit or underground mines.

Extracting minerals from the rock often involves the use of chemicals that can be harmful if released.

Images from Google Earth. Graphic by Malkolm Boothroyd.

Prospect of profit, or automatic land rights?

Free Entry System: Free entry grants any individual or company the right to stake a mining claim without the need for a permit or other authorization.

Mineral rights are automatically approved without consultation or consent from First Nations. These mining claims then hold tremendous leverage over land use planning decisions.

Acquisition: Rules about who can stake a claim and how.

Currently any adult can do so by pounding a few stakes into the ground and paying a $10 fee. Part of the free entry system.

Disposition: Rules for where mineral staking can happen and what mineral rights are granted.

Prospectors can stake a claim anywhere, unless the area has been withdrawn from staking (like designated protected areas). Part of the free entry system.

Mineral Tenure/Mining Claim: When an individual or company has tenure or a claim, they hold the rights to explore and develop minerals below the claim.

These are acquired through the free entry system and have to be maintained in good standing.

Exploration: Evaluating the mining potential of an area where a company has mining claims.

Exploration can involve building roads and cutting trails, disturbing wildlife with daily flights, building camps, and moving tens of thousands of tonnes of rock. Claim holders automatically have the right to explore, but specific exploration projects are subject to approval.

Mining roads cover Arch Mountain in the Kluane Wildlife Sanctuary.

Accounting for harm and public benefits

Financial Security: Hardrock (and a few placer) mining companies provide financial security to cover the costs of reclaiming and closing their mine site in case they abandon it.

This security amount is paid before production begins and reassessed every 2 years. The Yukon has a long track record of underestimating security needed, leading to expensive taxpayer funded cleanups and environmental harm left unsecured.

Royalties: Royalties are payments made to governments by mining companies, recognizing that the public and First Nations own the rights to minerals and should benefit from their extraction.

Placer miners currently pay just 37.5¢ per ounce of gold (the same rate as the early 1900s) and quartz miners are only required to make payments once they start making a profit.

Tailings: Tailings are waste materials left over after mining and can include harmful chemicals and metals.

Hardrock tailings are left in large ponds or are sometimes dried and stacked. Reclaiming tailings is a challenging task and some tailings will require treatment indefinitely.

Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board (YESAB): YESAB is responsible for reviewing proposed mining projects, and recommending mitigations and whether or not a project should go ahead to the Yukon government.

The YESAB process is separate from the new mining legislation but links very closely to it.

Abandoned Wellgreen quartz mine, clean-up costs are an estimated $15 million.

A changed landscape

Reclamation: Reclamation involves transitioning land to a different state after exploration and mining ends.

It’s usually impossible to fully restore the original ecosystem – simply too much has changed. The result is a different landscape where original values have been restored, replaced, or lost to different extents. Reclamation can involve filling in pits, recontouring the landscape, and planting vegetation. It’s expensive and hard to enforce, sometimes resulting in mines being abandoned.

Peat: Peat is a carbon-rich soil found in some wetlands that takes thousands of years to form.

Peatlands are vulnerable to placer mining because gold settles at the bottom or rivers and wetlands. When excavated, the peat decays and releases massive amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. Peatlands cannot be restored.

Permafrost: Permafrost is frozen soil that holds huge stores of greenhouse gasses like methane and carbon dioxide.

Typically we would say that permafrost is soil that is frozen year-round, but climate change and developments like mining are causing permafrost thaw.

Closure: The goal of mine closure is to return the site to a stable, non-polluting state and to meet reclamation goals.

This process takes many years. In the Yukon, a hardrock mine is considered closed when a Closure Certificate has been issued. Despite the number of mines that have operated in the territory, none have received this certificate.

Abandonment: When a mining company leaves a site without meeting the proper reclamation or closure measures.

Abandoned mines can pose significant risks to people and the environment, as contaminants and equipment are left unchecked. Reclamation and closure is then handled by the Yukon government with public funds.

The stages of placer mining show how in spite of the best reclamation efforts, natural peatlands can’t be restored.

2022: Our Year in Review

Written by Adil Darvesh

What a year 2022 shaped up to be!

We achieved some major milestones for conservation across the Yukon, many of which were thanks to your support. From filling up City Hall to oppose a busy road through McIntyre Creek, to writing letters on plans and policies, your help makes our work possible. Throughout the year our team hosted 13 events and had over 200 submissions from people who care about the Yukon’s wild spaces. We feel incredibly grateful for everything we accomplished.

Winter

Last winter we saw record breaking amounts of snowfall, and our team was right in the middle of it! Maegan and Candace recorded snow tracks throughout McIntyre Creek/Chasàn Chùa as staff, volunteers, and dogs ventured out to see how animals use the creek. Amelia Ford, a Grade 12 student at F.H. Collins joined us on a few treks, and wrote about her experience.

Photo by Maegan Elliott.

We also saw the first proposed development in the Peel Watershed. The Michelle Creek mining exploration project would overlap two Wilderness Areas, and in our eyes, it was the first test of the protections that the Peel Watershed Regional Land Use Plan put in place. This December, the Yukon Environment and Socio-Economic Board (YESAB) recommended that the project not go forward due to impacts on wildlife and First Nation wellness. This is incredibly good news, as it sets a high precedent for project approval in the Peel Watershed.

The Special Management Areas (set aside for protection) in the Peel Watershed were added to the Canadian Protected and Conserved Areas Database and now officially count towards Canada’s conservation targets. As a result the Yukon jumped to second place in Canada for conserved areas at 19.1%, just behind British Columbia. This is a big step for us to achieve 25% protection by 2025 and 30% protection by 2030. At the time, these were only federal targets, but with the Canada-Yukon Nature Agreement signed in early December, the Yukon Government has also committed to 25% by 2025. Polling conducted by Nanos Research confirms that Yukoners are supportive of bold conservation targets, so this is a step in the right direction.

Perhaps one of the biggest changes for our team happened in the winter. We moved into a new office! While the old office had lots of history and character, our growing team needed a little bit more room for staff. Over the past year we’ve held a few events welcoming you to our new space and it’s something that we hope to continue in 2023.

Spring

As the weather warmed up, so did our campaign for McIntyre Creek. Nicole Schafenaker joined us as our first ever artist in residence, supported by the International Centre of Art for Social Change FUTURES/forward program. Wanting to explore the wildlife corridor and its species through a creative lens, she hosted a series of events called Corridors: A Community Engaged Art Series in early May.

Photo by Maegan Elliott.

This came at the perfect time, as the City of Whitehorse released their draft Official Community Plan (OCP). This OCP will guide the direction of the city over the next decade and the draft version committed to working with First Nations, Government of Yukon, and Yukon University to designate McIntyre Creek as a park. This was a huge moment for those who were calling for protection of McIntyre Creek for many years. The draft plan, however, included language that would keep the door open for a “transportation corridor,” a busy road cutting through this wildlife corridor. Over the spring we called on you to submit comments welcoming the idea of a park, but asking to remove any language that would include a road.

In late November, the City of Whitehorse removed that language from the proposed OCP, after so many of you came out to City Hall meetings, submitted comments, and shared your love for McIntyre Creek!

Summer

This summer Ainslie Spence joined the team as our Conservation and Events Intern. She managed our booth at the local Fireweed Market and spoke with many of you about our campaigns and recommendations.

Ainslie identified that a lot of our materials were geared towards environmentally minded people, but we didn’t have very much for a younger audience. In response, she created a phenomenal resource for parents and youth titled Hutch’s Yukon Adventure. This colouring and puzzle book follows Hutch, the CPAWS Yukon husky, through his adventures around the Yukon in our key campaign areas. You can pick up a copy of the book at our office!

One of the areas in Hutch’s Yukon Adventure is the Beaver River Watershed, where our team has helped organize youth river trips in the past. This summer we traveled to Mayo to premiere films from the 2020 and 2021 Beaver River Watershed canoe trips. It was so awesome to show the community these movies, and promote the upcoming trip from Mayo to Moosehide.

Malkolm and I joined this summer’s canoe trip and had such a great experience connecting with youth and the land. We paddled along the Stewart and the Yukon rivers, taking time to stop at important historical sites, like the Old Village. Trips like these are important ways to continue sharing knowledge and foster a connection with people and place.

Our connection to place was also highlighted in our Plants of the Boreal walks. So many of you joined us on guided walks with plant experts to learn about what grows in our backyard. We took what we learned in these walks and at the end of the summer, Candace hosted a Winter Medicine Making Workshop to collect plants and share some of their different uses. It was a big success and something we hope to continue in 2023!

Photo by Paula Gomez Villalba.

Fall

As fall rolled in, so too did Environment Ministers across Canada. Many of you joined our calls for the Yukon Government to adopt similar targets to the Federal Government’s for 25% and 30% protection. At the time, the Yukon didn’t commit to any, but it’s possible they were laying the groundwork for the Canada-Yukon Nature Agreement signed in December by Minister Steven Guilbeault and Minister Nils Clarke. It sets aside funding for land use planning and protecting areas across the territory!

Nature conservation will be crucial for helping us manage the effects of climate change. We released a new report, written by Malkolm and Randi, about a significant blind spot in the Yukon’s climate strategy. Peat is an organic material rich in carbon, and disturbing it could release large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. Our report, The Yukon’s Climate Blind Spot addresses some of the concerns behind development in peatlands, and provides recommendations to manage them better. You can read a summary of the report here.

Photo by Malkolm Boothroyd.

The release of the Dawson Region Recommended Plan in the late fall kicked off a multi-month campaign to help you submit comments. We held a webinar and a few in-person events sharing our recommendations for a strong plan and sharing tools for you to make your own submission. Thank you to everyone who sent comments, we’ll eagerly await the Final Recommended Plan in spring 2023!

Winter

As the snow arrived and the holiday season began, we hosted our open house for the first time in a few years, and it was so great to be back! Our Pop-Up Shop and Holiday Open House highlighted some of our work and collaborated with some of our favourite artists and craft makers. We joined forces with the Yukon Conservation Society, our new neighbours, inviting you to a day out at “Conservation Corner.” Thanks to everyone who stopped by to say hello, learn about our work, and buy some goodies for the holidays.

Lastly, right after the open house our Outreach Manager, Joti, joined the CPAWS team in Montreal at the COP15 biodiversity conference. Joti shared some of her thoughts on our social media pages as she met with leaders across the country and shared ideas around protecting and conserving biodiversity through Indigenous-led conservation. Stay tuned for a summary from COP15 soon!

Phew! A lot happened this year. We’re so thankful to you for your support and for continuing to show up for nature. I had to skip over some other things that took place last year, but our Communications Coordinator, Paula, does a great job sharing our work on social media. Follow us to keep up to date!

Finally, I want to thank our previous Executive Director, Chris Rider. Over the past 4.5 years that I’ve been at CPAWS Yukon, Chris was a constant source of support, advice, and perfectly timed dad jokes. We’re all really happy that he is now taking lessons learned from our chapter onto the CPAWS National chapter in Ottawa and continuing to advocate for wild spaces across the country.

From the CPAWS Yukon team, thank you again for your support. We’re excited for 2023!

Peat beneath our feet

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba, Communications Coordinator

There is peat beneath our feet in wetlands that are thousands of years old. Soil so rich in carbon and history that it’s home to a plethora of plants, animals, and values. Peat forms when a shortage of oxygen in wet soils slows down the breakdown of mosses and other plants. Over thousands of years, layers of organic material build on top of each other, forming peat. We call places with these special soils peatlands.

Wetlands with peat come in many forms, like fens, bogs, and swamps.

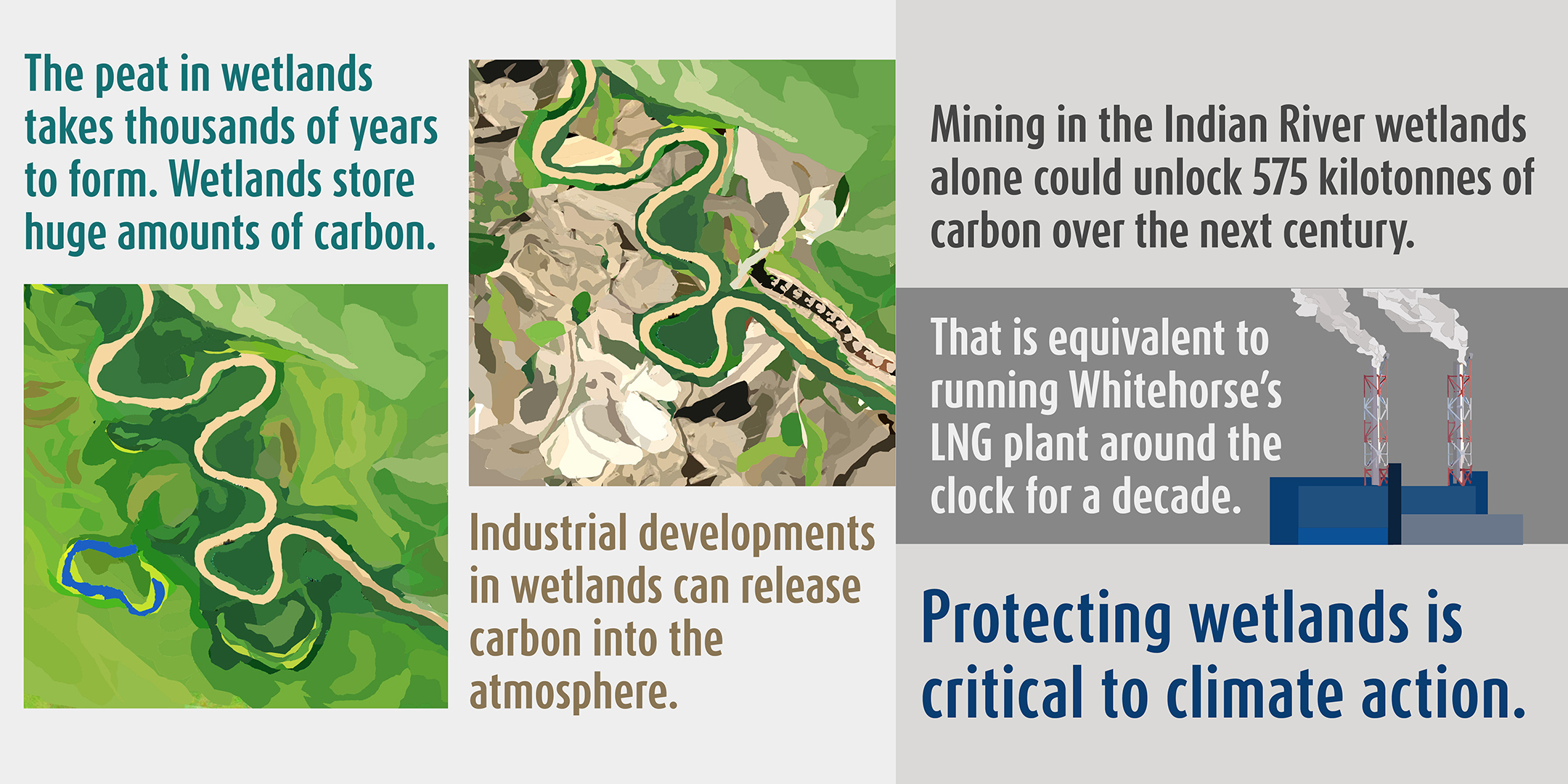

The organic material that peatlands store is rich in carbon. Around the world, peatlands hold more carbon than all the carbon humans have burned since the Industrial Revolution.

Beyond carbon, these ecosystems also hold important ecological and cultural values. They are home to moose, beavers and waterfowl, and a breadbasket for many First Nations citizens. Many people visit wetlands to hunt, fish and feel connected with the natural world.

Will we defeat the peat?

Peatlands are vulnerable to disturbances driven by climate change and industrial development. When disturbed, the carbon they store gets transformed and released as CO2, adding more fuel to the climate crisis.

In the Yukon, placer mining is one form of development that threatens peatlands because gold settles at the bottom of water courses in rivers, creeks and wetlands. When peatlands are excavated, they are all but impossible to restore and never have the same carbon storing potential as intact peatlands.

How much peat is at risk? The short answer is, we don’t fully know. National peatland maps don’t provide a fine scale picture of peatlands in the Yukon, and local mapping of peat has only happened in a few pockets of the territory. Without this information, we don’t know how much of the carbon held by peatlands is vulnerable to all kinds of development.

This makes emissions from peatland disturbance invisible – they don’t appear on the ledgers we use to track carbon emissions and aren’t part of our carbon cutting plans.

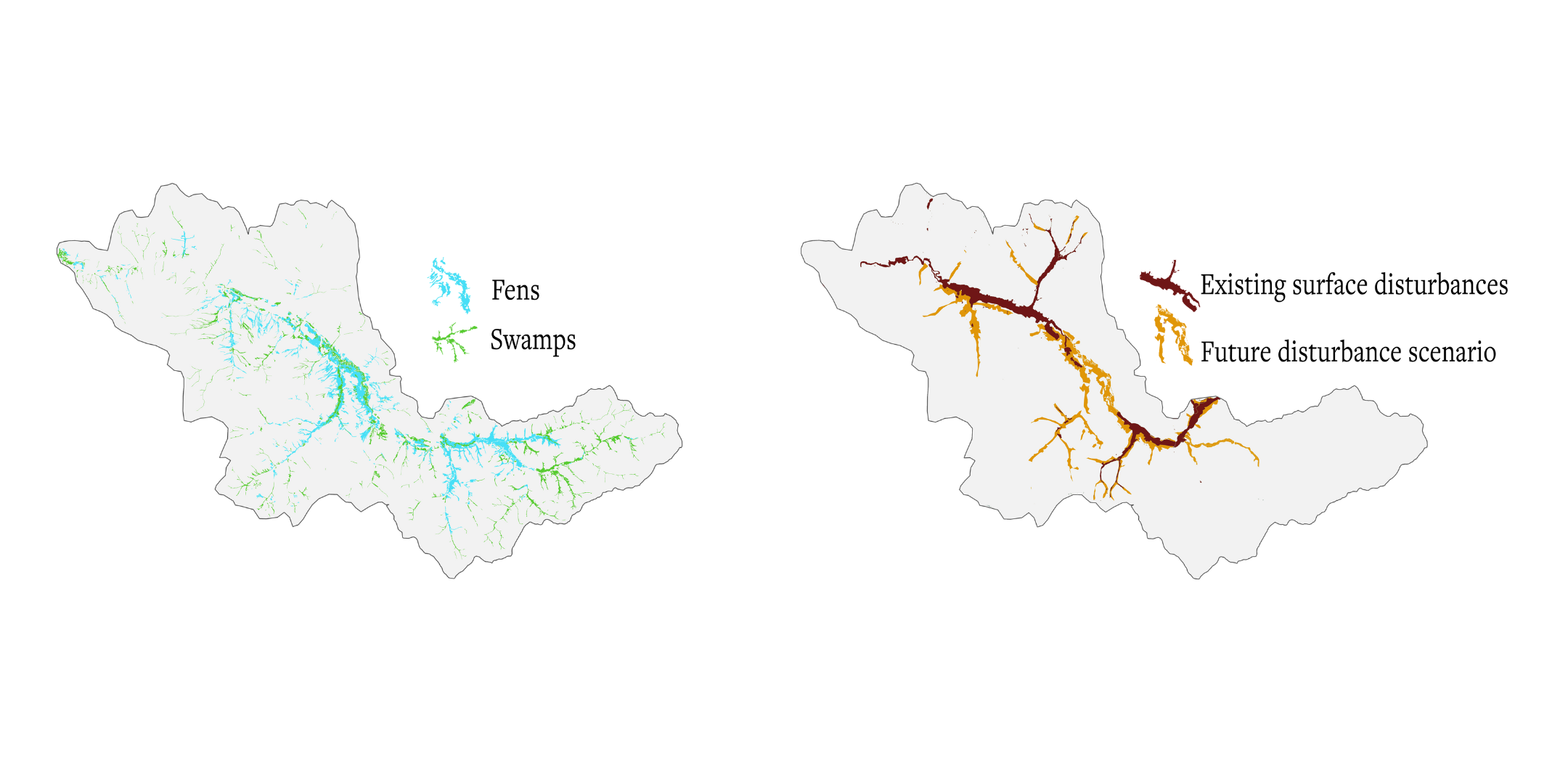

Wanting to shed light on these emissions, our team at CPAWS Yukon set out to understand the magnitude of carbon release from industrial development in the territory. Our investigation took us to the Indian River watershed, one of the few places in the Yukon with detailed wetland maps for this type of analysis.

The case of the Indian River watershed

The Indian River watershed lies within the territories of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and the First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun, about fifty kilometres south of Dawson City. The Indian River meanders through a wide valley dominated by fens and swamps.

Peat began forming in the watershed around six thousand years ago—at a time when woolly mammoths still roamed on Siberian islands, and fish had only recently returned to the lakes and rivers around Whitehorse following millennia of glaciation.

We estimate these peatlands store 1,837 kilotonnes of soil carbon—equivalent to over 6,700 kilotonnes of CO2.

The future of the Indian River watershed and its peatlands will be shaped by the outcomes of the Dawson Regional Land Use Plan. The good news is that the Recommended Plan prevents development in bog peatlands, but bogs only make up around 3% of all the peatlands found in the Indian River watershed.

Even with other modest limits on wetland and surface disturbance, the Recommended Plan would allow for significant amounts of new development in most of the Indian River watershed. These disturbances could release 575 kilotonnes of carbon over the next century—about as much carbon as flying a fully loaded jet the circumference of the earth 400 times.

A lot is lost when peatlands are developed. Carbon is released into the atmosphere, habitats are destroyed, and harvesting grounds used for millennia disappear.

While many of the Indian River’s wetlands have been lost forever, it’s not too late to protect those that remain. Join us in speaking up for these ancient wetlands. Public engagement on the Recommended Plan is open until Tuesday December 20.

What this means for the climate

The hundreds of kilotons we estimated could get released from peatlands in the Indian River watershed are from a single industry, in a watershed that makes up only 0.3% of the Yukon.

Peatlands covering three times the area of those in the Indian River overlap with placer claims in other parts of the Dawson Region. Peat is also found patchily across the Yukon: from the Old Crow and the coastal plain in the north, to MacMillan Pass in the east, to the Kluane Plateau and the Southern Lakes. There is a lot of carbon at risk.

But the Yukon’s climate change targets don’t account for carbon emissions from peatland disturbance, even though they are a major source of greenhouse gasses. This problem is not unique to the Yukon, and few countries currently report these kinds of emissions. In the recently released Global Peatland Assessment, the UN Environment Programme called on peat rich countries like Canada to report carbon from peatland disturbance and take urgent action to protect remaining peatlands.

“If we’re serious about acting on climate change, we must get serious about the protection, restoration, and sustainable management of peatlands. Wherever peatlands are allowed to be damaged or drained, harmful emissions will continue to be released for decades,” said Inger Andersen, Executive Director of UNEP.

It’s time for the Yukon to take action to protect peatland ecosystems and the carbon they hold. Protecting these wetlands is critical to climate action.

This blog post is a summary of our CPAWS Yukon peatland report – The Yukon’s Climate Blind Spot. You can find the full report at cpawsyukon.org/publications

On the water with land guardians

Written by Candace Dow

The Ross River Land Guardian canoe training was a long-awaited trip for all of us. Like so many plans from the last year, it was halted and redirected to 2022 to keep everyone safe during the pandemic.

Over 70 communities across Canada have Land Guardian programs. Guardians are the “moccasins and mukluks” on the ground in their communities. They manage protected areas, restore wildlife and plant populations, carry out water quality control, and monitor development sites. What they do is key to responsible land stewardship and brings jurisdictional authority back to Indigenous Nations.

Photo by Adil Darvesh.

The Ross River Dena Council in southeast Yukon is working to expand the role of Land Guardians. They have completed planning and are en route to establishing an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA). Current Guardians steward their land and water, ensuring what happens on the land aligns with their values and practices.

We partnered with Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y) to bring canoe training to Ross River (Tū Łī́dlini in Kaska). Y2Y works to promote healthy landscapes from Yellowstone to Yukon, including healthy communities, connectivity, and knowledge sharing.

This summer the training was met with a few challenges, but any good adventure usually is! We had such a huge snowpack last winter, bringing high water well into the summer months. And since this was also the first summer without Covid restrictions, both the instructors and participants had many things on the go!

Between the Guardians and some brave youth, 7 participants went out on Whiskers Lake for the first day of training. It is always nice to see so many youths interested and taking part in connecting back to the land and gaining some water safety skills.

Photo by Adil Darvesh.

We are hopeful for a final training day this fall. The goal for the final day will be to experience the river just as the Guardians would on an actual patrol. Navigating rivers can be a challenge, but with real-time training, Guardians can learn about exact locations they need to be aware of when out on patrol and safely steward their lands and waters. We are grateful to everyone that made this happen.

To the Land Guardians, thank you for doing such important work! Happy Paddlin’

Every ending is really just a new beginning

Written by Chris Rider, Executive Director

Dear Supporters,

I am writing this letter to share that November 4th will be my last day as the Executive Director of CPAWS Yukon.

I am so thankful for all the opportunities and experiences I have had with this organization since I started in 2016. I am especially thankful for the relationships I’ve been able to form, and the trust that has been put into myself and our team by First Nations citizens and leaders across the Territory. I will never forget it, and I will never take that trust for granted.

Earlier this summer, I had the privilege of doing a paddling trip in the Peel Watershed with Nahanni River Adventures. It was my first time paddling on the Wind River, and I felt an incredible sense of gratitude for the opportunity to be out there. One evening, I stood on a ledge looking out at the river and the mountains. The beauty of this special place washed over me, as I reflected on how lucky I am to have been part of protecting a place that is special to so many people.

Although I am sad to move on, I am also excited to see what comes next for CPAWS Yukon. I have so much confidence in our team of smart, talented and wise people. I know that they will continue to do incredible things.

My next step is to start a new role within the CPAWS family. I will be joining the team at CPAWS national in Ottawa, as their National Director for Conservation. I am excited for the challenges and opportunities that this will bring, and happy I will have the chance to remain connected with the work here in the Yukon.

If you are reading this and thinking you might be a great fit for the next Executive Director of CPAWS Yukon, I encourage you to apply. You don’t need a background in conservation or ecology, but we are looking for a strong, compassionate leader to lead this special team. I hope that will be you! You can find the full job listing here, on our website.

I will close by saying thank you to my Board of Directors – past and present – for your unwavering support over the years. I am lucky to have worked with every one of you.

Onwards and upwards,

Chris Rider

Op-Ed: In the Yukon, nature is thriving. We can keep it that way

Written by Chris Rider | Aug 28, 2022

Photo by Malkolm Boothroyd, front ranges in Kluane.

Read the full editorial as published in the Yukon News on August 28th, 2022.

—

Op-Ed: In the Yukon, nature is thriving. We can keep it that way

Nature surrounds us in the Yukon. It is what makes living here so special. There are endless possibilities for outdoor adventures, and when you’re out on the land, it’s common to go days without seeing another human.

Yukoners – both First Nations and non-First Nations – are able to fill their freezers with caribou, bison, moose and sheep. Although we maintain sensible restrictions on harvest numbers in many areas, it’s still straightforward for anyone living here to get a tag. This is an opportunity that has largely been lost to people living in the provinces, where they often have to wait years for a chance to hunt anything other than deer.

The fact that the Yukon still has healthy ecosystems is something we can all celebrate. It means we aren’t facing the same crisis as much of Canada and the world. Large-scale protection in the Peel Watershed and northern Yukon helps ensure that in parts of the Territory this will remain the case.

My fear is that despite these meaningful wins for nature, we still risk sleepwalking our way into the same crisis that’s facing the rest of the country. By setting meaningful conservation goals, Yukon can protect the cultural (traditional hunting areas, sacred places, etc.) and ecological values we hold so dear.

What could a large decline in the health of wildlife populations mean for the Yukon? First, it would result in a loss of culture. This is particularly the case for the First Nations people who have subsisted off the land for millenia, but it would impact the lives of every person who hunts, traps, fishes or gathers. It would also impact our tourism industry and economy in significant ways.

We can get a glimpse of the future by looking Outside. Globally, plants, animals and insects are disappearing at a rate faster than at any time since the extinction of the dinosaurs. It is a crisis caused by humans – we have destroyed huge swathes of habitat, over-fished and hunted, polluted the air and water with chemicals and plastics, and are causing the climate to warm.

Canada is not immune to this biodiversity crisis. According to researchers, 20% of all wildlife species in Canada are imperiled to some degree, and a recent study by WWF found that of nearly 1000 species of animal that could be tracked, over half had declined since the 1970s. This is why in the provinces, people are talking about the urgent need to take action to halt and reverse biodiversity loss.

It’s tempting to think that we don’t have to worry here, especially because everywhere we look, there are miles of undeveloped land. Unfortunately, what sometimes seems like a small amount of development can add up and have a big impact. Roads can increase hunting access and create a spiderweb of new developments. Mines can also have an oversized impact when they’re located in key wildlife habitat, or contaminate water. This risk is particularly high in the Yukon, where our harsher climate means wildlife needs comparatively large intact areas to get the nutrition they need to survive. This is why we tend to see fewer animals when we’re out and about than you might in warmer climates.

The good news is that it’s not too late for the Yukon. First Nations are working hard to protect their lands and waters – we simply need to follow their leadership. Tools like the Chapter 11 land use planning process and Indigenous Protected & Conserved Areas (IPCAs) can provide a path to expanded conservation across the Territory. We can use these tools to protect large, connected areas that will preserve the ecological and cultural values that make this such a special place to live.

In 2021, CPAWS Yukon and the Yukon Conservation Society commissioned DataPath to run independent polling to learn more about Yukoners’ perspectives about the environment. They found that 78% of Yukoners believe that we should aim to protect at least 30% of our land and water by 2030. There are few issues that more of us agree on.

Canada’s environment ministers will meet in Whitehorse on the last two days of August to discuss the state of the environment and many other issues. Yukon has the opportunity to show that we are leaders by formally committing to strong conservation targets for the Territory. I encourage our Government to do this before it’s too late.

Is this the face of climate change in the Yukon?

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba. Title photos by Adil Darvesh.

Every time I go outside, there’s something that makes me ask myself, “Is this the face of climate change in the Yukon?”

Flood warnings. Landslides. Wildfires. Daily lightning and thunder. Road closures. Power outages. Hot weather. Relentless mosquitos.

And it’s all connected. Temperatures last winter were higher than normal with record-breaking snowfall. All of this snow had to go somewhere as summer arrived, leading to rising water levels and loads of standing water for breeding mosquitoes. It’s strange to think that even with this surplus of water, there are over 100 active wildfires in the Yukon, heat warnings, and thunderstorms.

Cue climate change.

Our history is no stranger to changing climates. For millions of years, glacial and interglacial cycles have melted and formed ice sheets across the Yukon. Most recently, the Bering land bridge that connected North America to Siberia flooded, sea levels rose, and glacier melt carved rivers across our new landscapes. The difference is that those changes happened over tens of thousands of years, not over the last two centuries (how long humans have been burning fossil fuels). There was time for many plants and animals to evolve, adapting to the changing conditions or moving to new areas.

Photo by Malkolm Boothroyd

Now with evacuation alerts in place across Mayo, Keno, Teslin, and other communities, we are at the frontlines of the climate crisis. Scientists are often reluctant to say that a specific event is caused by climate change because that can be hard to prove. There are lots of forces interacting with one another. A wildfire, for example, might be caused by lightning or unattended campfires, but it’s also affected by wind, temperature, leaf litter, and moisture in the plants. What’s certain is that climate change causes events like wildfires and floods to become more frequent and more extreme. It also disproportionately affects Northern Canada. According to Environment Yukon,

“The Yukon’s average temperature increased by 2.3°C between 1948 and 2016. Winter temperatures increased by 4.3°C over the same time period. This is close to three times the rate at which global temperatures are rising.”

When I first started learning about climate change, I was overwhelmed by the amount of information, statistics, and models. I found myself reading article after article, trying to understand the relationships between acid rain, sea level rise, glacial melt, changes in biodiversity, etc. When I finally emerged from that rabbit hole, I still didn’t fully understand. It was frustrating and often times paralyzing. A lot of it was doom and gloom. How could a single person take action in a crisis that reaches all corners of the planet? Nowadays there’s a term for these thoughts and emotions – ecoanxiety.

Then I realized that as individuals we don’t need to have all the answers. Change comes from collective action.

Photo by Paula Gomez Villalba

All around us there are people passionate about connecting with the land and protecting our productive forests and rich ecosystems. Wildflowers are blooming, buzzing with bumblebees spreading their pollen. Caribou are welcoming the next generation of young, and flickers are starting to peak out from their nests, eager to explore their forest homes. By starting from a place filled with gratitude and a sense of community, we can find our own special ways to fight climate change.

Learn how you can find joy in climate action in this talk by biologist and writer Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson:

CPAWS Yukon works to connect government, businesses, first nations, and citizens so that we can make sure the future of our wild spaces reflects our cultural, personal, and ecological values. Sometimes that means working behind-the-scenes, but a lot of the time we also share opportunities where people like you and I can make our voices heard.

Many species tolerate the existing roads in McIntyre Creek. Why is CPAWS Yukon opposing a new road?

Written by Malkolm Boothroyd, Campaigns Coordinator

Whitehorse’s Official Community Plan will help to determine the future of McIntyre Creek/Chasàn Chùa. Your input can shape this plan! Email your thoughts to ocp@whitehorse.ca or fill out the City’s survey.

Coyote pups tumbling about in a clearing. A calf moose trotting behind its mother’s towering legs. A pine marten standing up its hind legs and looking straight into the camera. These are a few of the thousands of images captured by the trail cameras we set up throughout McIntyre Creek last summer, and have been sharing on social media. But there was more to this project than documenting the adorable wildlife of McIntyre Creek.

We set out on our wildlife study because we wanted to understand how developments like roads and subdivisions impact the wildlife that depend on the creek. Last week the City of Whitehorse released its draft Official Community Plan—promising to work towards a park in McIntyre Creek—but also leaving the door open to a major road through the lower section of the creek. The Official Community Plan will help determine the future of McIntyre Creek, which means it’s a good time to take stock of our wildlife study.

We’re part way through analyzing our data. It surprised me, but in most cases roads didn’t have a statistically significant impact on wildlife distributions. One exception was moose, which avoided areas with lots of roads, while deer were more likely to be found in heavily roaded areas. Deer have a higher tolerance of people than other ungulates, and may favour places with higher human densities in part because their predators avoid these areas. Species like lynx, coyotes and snowshoe hares seemed largely unaffected by roads.

Our trail cameras only recorded a few grizzly bears and one single wolf, all in parts of McIntyre Creek with few roads. It’s possible that roads are negatively impacting these large predators, but our sample size was much too small to draw any statistical conclusions. These are preliminary results, and we haven’t finished analyzing all of the data we collected. These findings are definitely not what I expected, but they’re good news. It means that there’s still a lot of really good wildlife habitat throughout McIntyre Creek, and that most species can tolerate the existing amount of roads in the area.

There are lots of things this study doesn’t tell us. Our study can’t predict the impacts of building a new road through McIntyre Creek, or expanding the Alaska Highway and Mountainview Drive to accommodate more traffic. Building a third major road would be a big change for McIntyre Creek, and one that there’s no going back from. We’re fortunate to live in a city that is so rich in wildlife and wild spaces, but that could change if we take it for granted.

There are other reasons to be skeptical of a new road through McIntyre Creek. How will building a road from the roundabout on Mountainview Drive to the Alaska Highway near Kopper King alleviate traffic congestion? Anybody driving from Whistlebend into Whitehorse would be adding an extra kilometer onto their commute along with two left hand turns across busy roads, only to end up at the top of Two Mile Hill. There are values-based considerations too, like cutting a major road through an area full of walking and biking trails. And of course there’s the climate emergency. Building a new road strikes me as a 20th century solution to traffic problems— when the future of sustainable urban development depends on mass public transit and active transport.

The City will have to think about the road from a lot of angles—how wildlife use the creek, the connections that people hold to this place, and what the future of transportation looks like in Whitehorse. The results of our wildlife study may not lend themselves to making simple, decisive statements about the impacts of the proposed road on the wildlife of McIntyre Creek, but that’s fine. The prospect of a road through McIntyre Creek has always been a complicated question, and one that will reflect Whitehorse’s priorities as a City.

What’s your vision for the future of McIntyre Creek? A busy new road could change what we love about McIntyre Creek. We have a week to tell the City we don’t want it. Send an email to ocp@whitehorse.ca, or fill out the City’s survey by June 12th.

Corridor Conservation: My story as a youth inspired by McIntyre Creek

Corridor Conservation: My story as a youth inspired by McIntyre Creek

Written by Amelia Ford, McIntyre Creek Project Volunteer

As a grade 12 student at F.H. Collins Secondary School, I was given a project to complete within the final months of high school that explored a hobby, interest, or possible future career path. Essentially, the project could be anything under the sun, as long as it showed my focus and enthusiasm. Initially I was overwhelmed, as there was a huge variety of possible interests I could explore, but I ultimately settled with volunteering for an organization of my choice, CPAWS Yukon. Given my strong interest in the environment and conservation, working with such an organization was a pretty big deal. From December to March I joined Maegan Elliott, the lead behind the McIntyre Creek/Chasàn Chùa project, and helped both in the field and from my computer.

Originally, I was not very aware of the importance of McIntyre Creek or the significant threat it faces with our growing population. The City of Whitehorse has proposed developmental options to meet the needs of a growing city, including the expansion of Porter Creek, which would cut into the heart of the McIntyre Creek area. On top of that, the future expansion of the Alaska highway and increased traffic levels also pose a danger to wildlife in the area.

Though the expansion of development in these areas may be convenient in solving the problem of housing, the resources and home of many species living at McIntyre Creek would be in trouble. The Yukon is known for its vast lands and diversity of plants, animals, and ecosystems. McIntyre Creek subsequently plays an important role in connecting our wildlife to these different lands, which is what CPAWS and other organizations are trying to show through snow track surveys, collecting data, discussions, and advocacy.

I completed a snow track survey in McIntyre Creek, and even within a small section of the area Maegan and I counted the tracks of many unique and different species. The survey involved traversing a 1.5 km long triangle, identifying and recording all of the tracks that cross the transect route, which in my case involved trudging through knee-deep snow and an unexpected spring crossing. I was shocked by the range of species that pass through or live in the wildlife corridor (it’s not just squirrels and the occasional bear). On just one transect we counted the tracks of lynx, deer, martens, hares, you name it! I further realized the variety of species when I entered data from multiple different surveys across McIntyre Creek into the main spreadsheet, which is full of a diverse range of animals. There’s evidently a large volume of wildlife that uses the corridor – however, it is also used by humans just as frequently.

This area plays a role in the mental well-being of our communities, especially during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. With a decrease in indoor gatherings, many took to the outdoors to find solace from the stress caused by the virus. Whether it be skiing, hiking, snowshoeing or walking, the McIntyre Creek area has visible evidence of use by our city’s population. And not just for recreational purposes – this area is also frequented by Yukon schools for educational purposes and for learning about our territory’s biodiversity.

From initially knowing next to nothing about this issue, I am super grateful to have been given the opportunity to work with CPAWS and learn about the significance of the land I use every day. Working on this project also showed me just how important actively making a difference can be. It’s easy to become overwhelmed with the constant onslaught of environmental threats our world faces, paired with the devastating impacts of our changing climate, but it is also important to remember the power and change we can create by advocating for these issues (especially as youth). For this reason, I encourage you to research and speak up about these types of issues, and to communicate with others and your community so we can conserve this land we are so fortunate to call our backyard.