Blog

- Wildlife Campaigns

- Uncategorized

- Publications

- Protecting our Wildlife

- Protecting our Wilderness

- our stories

- NewsArticles

- News

- MDS

- FrontPageOurWorkSlider

- Forest Campaigns

- Events

- Climate Change Campaigns

- Campaigns

- BlogPeelWatershed

- BlogNorthernTutchone

- BlogMcIntytreCreek

- BlogDawsonRegion

- BlogBeaverRiver

- BlogArcticRefuge

- Blog

Calculating the future of the Indian River

Calculating the future of the Indian River

Header Image: Indian River near Sulphur Creek, by Malkolm Boothroyd

Written by Malkolm Boothroyd, Campaigns Coordinator

What does the future of the Indian River look like?

That question was at the front of my mind as I read the draft land use plan for the Dawson Region. One number jumped out—5%. That’s the amount of disturbance the land use plan would permit in the landscape management unit that encompasses the Indian River, and the rest of the goldfields. 5% may not sound like much disturbance, but when you look closely it’s shocking.

I explored some of the implications of this number in this story map. I decided to go into more depth in this blog because a) it’s a topic that fascinates me, and b) it’s good practice to be transparent about the math and the assumptions that go into making conclusions like the ones I made in this story map.

I’ve been drawn to the Indian River ever since I canoed it last summer. It’s a river that few people ever paddle, and it’s clear why. In places the river is so coiled that you have to paddle three kilometres of river to make it six hundred metres as the raven flies. Some parts are choked with fallen trees, and we lost count of the number of portages we made. Sections of the river are engulfed by placer mining, and the noise of machinery drowns out the sound of the river. Still, there are places where the river carries you far away from the mines. Then you’re surrounded by ancient trees, and you drift by river banks that are crisscrossed in moose tracks.

The Indian River wetlands have long been a breadbasket to the Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin, but many citizens have expressed that they no longer feel comfortable hunting and fishing in these areas. Sorting out the future of conservation and development in the Indian River was one of the big challenges facing the Dawson Land Use Planning Commission, and it’s one part of the plan that needs some big improvements.

Okay, time for some math.

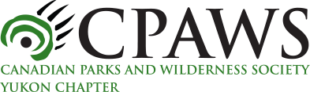

The first question I wanted to answer was how much new development the land use plan would permit. The Indian River is part of Landscape Management Unit (LMU) 12 – East – Nächo dëk. This is designated as an Integrated Stewardship Area IV, the designation that permits the greatest possible amount of development. Surface disturbances (such as areas covered by mines, gravel pits, work camps, roads and farmland) are allowed to cover 5% of the landscape. Linear disturbances (like roads, trails and cut lines) can cover 5 kilometers per km2. LMU 12 is 6,606 km2 in total, so that means there could be up to 330.3 km2 of surface disturbances, and 33,030 kilometers of linear disturbances.

I started by looking at the existing disturbance maps for LMU 12. These maps are around ten years old (new maps are expected next spring), but they’re still helpful. The disturbance maps show there are already 113 km2 of surface disturbances and 3,552 kilometers of linear disturbances.

For the purposes of my analysis for the story map I created one single disturbance polygon by combining the surface and linear disturbance layers. I transformed the linear features into polygons by applying a 10 metre buffer around roads, and a 5 metre buffer around all other features. These numbers are a rough estimate, though I measured the width of the Hunker Creek Road using Google Earth, and it seems like the right ballpark. This new disturbance layer was 152 km2 in size.

There’s one big catch in the land use plan’s 5% disturbance limit. It’s calculated by averaging out disturbances across the entire landscape management unit, but in reality disturbances are not uniformly distributed. Almost all the development within this area is associated with placer mining, which closely traces the bottoms of valleys—which also happen to be some of the most fragile and biodiverse environments within the landscape. The way the land use plan is written, a whole lot of development could be packed into valley bottoms, while still keeping within the 5% limit.

I was curious to know exactly how much development occurs within the bottoms of valleys. For the purposes of this analysis I defined a ‘valley’ as an area within 500 metres of a river, or 250 metres from a stream. I excluded areas higher than 700 metres. These valleys make up 1,656 km2. That’s 25% of LMU 12, but 76% of disturbances fell within these valleys. Put another way: my combined disturbance polygon averaged out to 2.3% disturbance across all LMU 12, but reached 7% disturbance within valley bottoms.

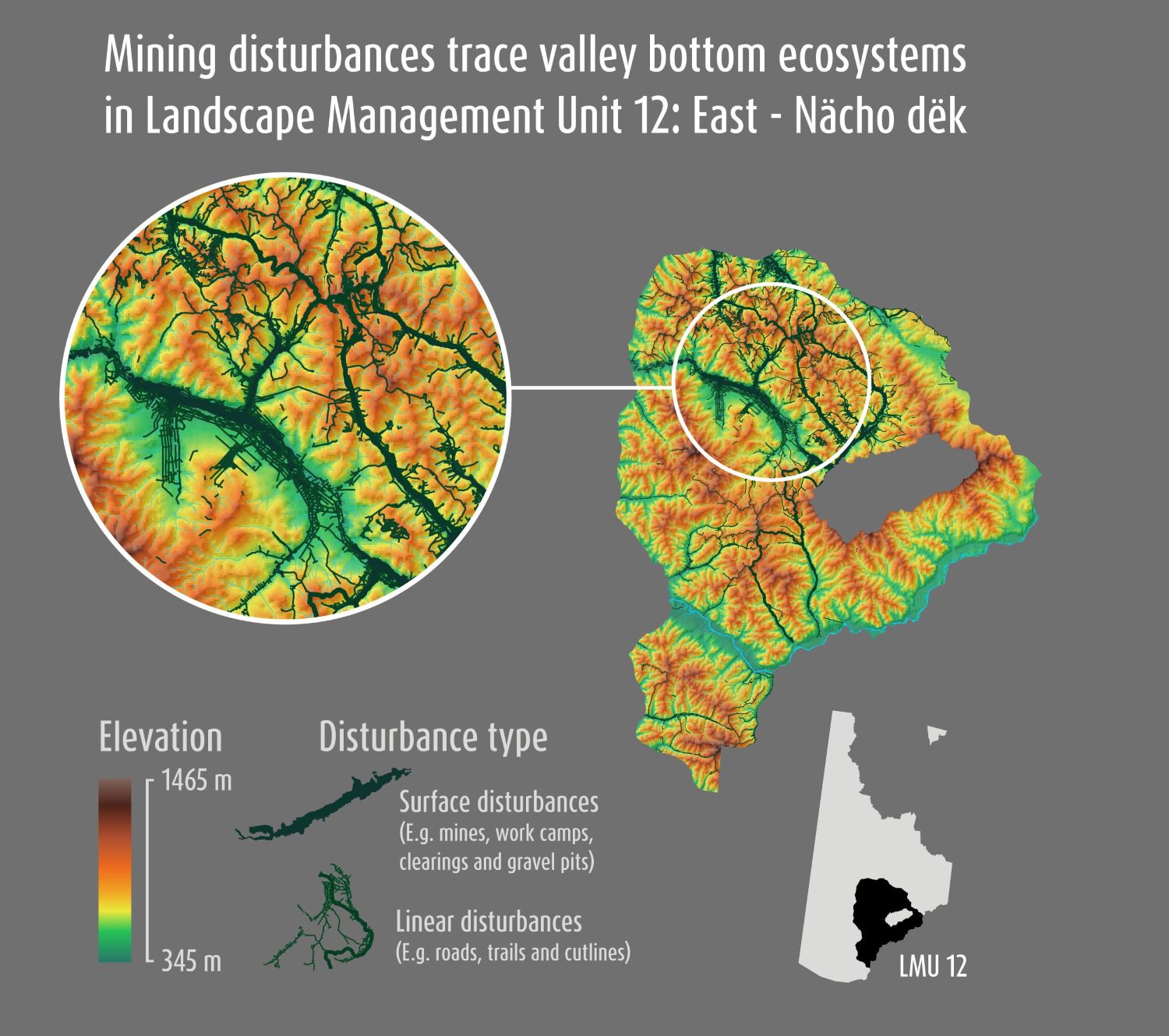

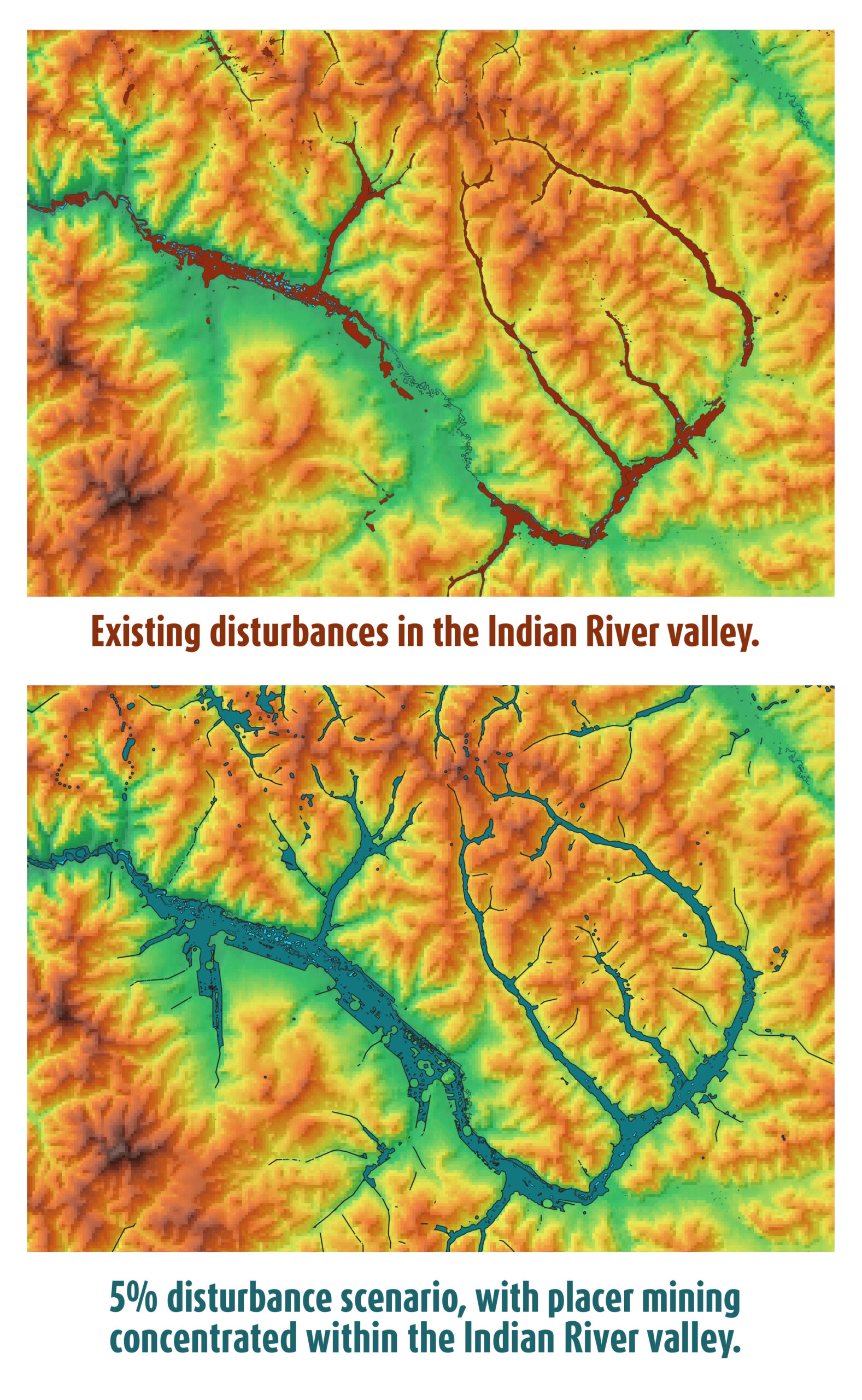

Next, I extrapolated this to a scenario where disturbances consume 5% of LMU 12. If new developments follow the same patterns as prior disturbances, then disturbance levels within valley bottoms could reach 14.8%.

This is already a tremendous amount of disturbance within valley ecosystems, but it doesn’t give the full picture. This assumes that development would be spread evenly throughout the valleys of LMU 12, but in reality disturbances are concentrated within the Indian River watershed. I wanted a picture of what development around the Indian River could look like.

To do this, I first worked out how much new development could be added to LMU 12. If there’s currently 152 km2 of disturbances at last count, then there’s room for an additional 178 km2 of disturbances within the 5% disturbance limit. Some of this would be accounted for by the footprints of linear disturbances, so I applied the ratio of surface: linear disturbances (113:39) within my combined disturbance polygon and estimated from 178 km2 of disturbances, 131 km2 could be new mining disturbances. That would bring the total mining-related disturbances within LMU 12 to 245 km2, plus 85 km2 of roads, trails, cut lines and so forth.

Finally, I used QGIS to create a 245 km2 large polygon layer. I did this by expanding existing disturbances, and creating new disturbances in QGIS from lands staked for placer mining. Finally, I removed rivers and “undisturbed” wetlands from the land available for disturbance. The land use plan states that there shouldn’t be new mining in undisturbed wetlands, but what an “undisturbed” wetland is, isn’t clearly defined. For the purposes of this map, I decided to define “undisturbed” wetlands as wetland areas 100 metres or more from existing disturbances. In reality this will be a much more complicated process, which I’ll leave up to hydrologists and land use planners.

So here are the maps.

It’s important to note that these maps are just a scenario, and there’s no guarantee that these specific places would be mined. Rather, these maps show that the draft plan would allow for tremendous amounts of new development—and these disturbance limits aren’t very limiting.

There’s already been a lot of mining along the Indian River, but that doesn’t mean we should write the valley off as a wasteland. There’s a lot that’s worth conserving. I hope the Dawson Land Use Planning Commission will make some big changes to the land use plan so that the Indian River gets the protection it deserves.

Op-Ed: Yukon at a crossroads with Fortymile caribou herd

Written by Malkolm Boothroyd | Oct 5, 2021

Photo by Malkolm Boothroyd.

Current land use planning for the herd’s range offers an opportunity to keep the volatile population on the right path.

Read the full editorial as published in The Narwhal on October 5th, 2021.

—

Op-Ed: Yukon at a crossroads with Fortymile caribou herd

About twenty caribou have blocked the road. I pull over to the shoulder and park. It’s a hot July day on the Top of the World Highway, about 90 kilometres northwest of Dawson City, Yukon. A light haze hangs in the air, smoke from wildfires burning across the border in Alaska.

It’s the Fortymile caribou herd. Some caribou are lying on the gravel, others stand as three-week-old calves nuzzle around their legs. Velvet still coats the antlers of the bulls. Several hundred more caribou are scattered across the mountainsides ahead, and a few dozen are bedded among the stunted alders that furnish the rocky outcrops above the highway.

It’s been slow going all afternoon. I’d only just gotten back on the road after waiting three hours for a hundred caribou to clear the highway a few kilometres back. I open the truck door and step out, trying to make as little noise as possible. I tiptoe around the back of the truck to where my companions, Chase Everitt and Chris Clarke, have parked. Chase is a fish and wildlife technician and a Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin citizen. Chris works with the First Nation’s Land Stewardship Project.

The next moment I’m distracted by the roar of wheels churning through gravel. I look up in time to see a white SUV rounding a corner towards us. The vehicle speeds by without slowing down, quickly closing the gap to the caribou. Chris hammers the horn of her truck, and finally the SUV shudders to a halt and reverses back towards us. “There are laws about not harassing wildlife,” Chase tells the driver, a clean shaven guy with greying hair and Alberta plates. “You need to wait until the caribou move off the road.”

“Are you serious?” the man snaps.

He starts venting about public health measures adopted to control the coronavirus pandemic and then circles back to the caribou. He suggests he should be allowed to do what he wants.

“I’m sick of people telling me what I can’t do in my own country.”

There are stories from a hundred years ago when Fortymile caribou were so numerous that it took days for the herd to cross the Yukon River. The paddlewheelers that plied the river between Whitehorse and Dawson would have to moor up and wait for the caribou to finish crossing. The herd has been through staggering crashes and spikes in the intervening time, from numbering in the hundreds of thousands, to just a few thousand in the 1970s. Concerted efforts to recover the population began in the 1990s. Wildlife authorities in Alaska began an expansive program of predator suppression, while Yukon hunters and the Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin stopped harvesting the herd. By 2017, the herd had rebounded to more than 80,000 caribou.

There’s something poetic about the Fortymile herd recovering to a point where it can once again stop traffic, but our Albertan friend doesn’t seem amused. He pulls a U-turn and speeds back towards Dawson, waving his middle finger at us as he disappears.

The Fortymile caribou are one of those animals that everything else seems to revolve around. Bears and wolves follow in the wake of the herd, and the footsteps of countless generations of caribou are etched into the mountainsides. Fortymile caribou sustained the Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin, and caribou meat helped to feed the tens of thousands of prospectors who flocked north during the Klondike Gold Rush. This excessive hunting by newcomers drove the herd to crisis, and displaced the First Nation’s harvest. The Fortymile caribou may have faded away for a time, but its recovery is bringing new optimism, as well as new fears.

I’d come here hoping to get photos and videos of caribou to use in the advocacy work I do with the Yukon chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. The Yukon is in the middle of land use planning for the Dawson region, which will determine which parts of the herd’s range will be protected, and how much development can happen in the rest. This is a critical time for the Fortymile caribou. Some biologists worry that food shortages within the herd’s range could trigger another population crash. Meanwhile, new mining developments could encroach upon the herd’s remaining range. The next few years will shape the future of the herd for decades to come.

The memory of the Fortymile caribou still lingers on the landscapes they once inhabited. Ancient caribou trails line mountains in the Dawson Range, even though the herd has not been seen in these lands for more than 60 years. The herd once ranged throughout the central Yukon and Alaska, some winters migrating almost as far south as Whitehorse. One traveller described canoeing down the White River in 1909, where “for forty miles we were running through one continuous mass of caribou. The narrow valley and high bald mountains on either side, swarmed with the animals.” In the 1920s, the herd probably numbered around 250,000, according to Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game.

Profligate hunting of the Fortymile caribou began at the turn of the 20th century and accelerated through the 1930s as new roads opened the highlands to hunters. Historical accounts from game officers in Alaska described people firing into herds — leaving some caribou crippled, and others dead with their meat left to waste. In a single season, 10,000 caribou were killed by hunters in one game district in Alaska. One warden wrote that “most people are content to believe that the animals are in countless numbers that cannot be exhausted.” By the 1930s, the herd was in serious decline. Wolves and wildfires likely worsened the herd’s freefall, and by 1940 fewer than 20,000 remained. The herd had recovered somewhat by 1960, only to plummet again. By 1975, there were only around 5,000 left, according to the Yukon government. The once expansive range of the Fortymile caribou contracted to its very core, in the hills between Dawson City and Fairbanks.

Thanks to decades of recovery work, there are more than 10 times as many caribou in the Fortymile herd as there were in the 1970s. Still, there hasn’t been a corresponding increase in the herd’s range. It’s hard to say why. The networks of mines that extend south from Dawson City might deter caribou from crossing these habitats, but there are other explanations too. Trees and shrubs are flourishing at ever higher elevations as climate change heats up the north. That means the alpine migration corridors, those places above treeline that once unlocked the central Yukon, may now be too overgrown for caribou to use. It’s also possible that the Fortymile herd has lost its collective memory of its old range and the pathways leading there. Migrations have to be learned, and this knowledge could have died out decades and decades ago with the last of the caribou that ventured into central Yukon.

The herd’s failure to reestablish its old range means that caribou are packed tightly within its core range. Some biologists suspect that the herd has surpassed the carrying capacity of the ecosystems it inhabits — essentially that there aren’t enough grasses, sedges and lichens to sustain 80,000 caribou. Insufficient food makes it less likely for cows to give birth, and more difficult for the calves that are born to survive. There are fears another population crash could be looming. This has led wildlife managers in Alaska to push for more hunting to bring the herd’s population down. The Yukon government and the Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin First Nation recently agreed on a new management plan, which includes a small hunt for non-First Nations hunters. It’s a new era for the Fortymile caribou.

The hills surrounding Dawson City trend steadily higher as you go west towards Alaska, and slowly the hilltops begin to shrug off the cloak of the boreal forest. These tundra ridges are the heart of the herd’s summer habitat. In the windswept highlands there’s relief from mosquitoes, and lichens and grasses to feed on. Fortymile caribou give birth to their calves across the border in Alaska, then in late June and early July huge congregations of caribou move into the Yukon, following the ridgelines to skirt the tangles of spruce and alder that fill the valleys.

Many of these ridges are also lined with mining roads, winding away towards placer mines in the valleys and hardrock exploration properties in the alpine. Over a quarter of the herd’s core range is blanketed by quartz mining claims. Study after study — from Alaska and the Yukon, to Alberta and the Northwest Territories — warn of the impacts to caribou from industrial development. Developments like roads, mines and oil and gas infrastructure displace caribou from ecosystems, interrupt migrations, and make it easier for predators like wolves to prey on caribou.

Big decisions are looming about which parts of the Fortymile caribou herd’s range will be conserved, and which areas will stay open to mining. In the Yukon, decisions like these are made through the territory’s land use planning process, born from the Umbrella Final Agreement between Yukon First Nations and the Crown. In June the Dawson Land Use Planning Commission released the first draft of its plan. The plan divides the Dawson region into 23 different landscape management units, each with its own land use designation. Forty-five per cent of the region has some form of conservation designation, and the rest is open to varying levels of development.

The plan recommends strong protections for the very core of the herd’s range within the Matson Uplands, a mountain range along the Alaska border, west of Dawson City. But the remainder of the herd’s key range is at risk. Most of the herd’s remaining critical summer range falls within the ‘Fortymile Caribou Corridor’ landscape management unit. This area is divided by elevation, with high elevations open to limited development and low elevations open to moderate development. In alpine habitats, the industrial footprint cannot exceed one quarter of one percent of the landscape. This threshold is relatively low, but it’s calculated by averaging disturbances across the 800 square kilometres of alpine within the unit. High amounts of disturbance could still occur within small areas. Any mining development within ridgetop habitats could interrupt caribou migration corridors, or displace them from key summer habitats.

With a few modifications, the Dawson Land Use Plan could provide strong protections for the Fortymile caribou. It’s critical to keep alpine ridges free from new industrial development, and the plan should designate these habitats as conservation areas. The plan should also ensure there’s ample wintering habitat for Fortymile caribou. Caribou disperse across lower elevations in the winter, and developments within core wintering habitats should remain within levels caribou can tolerate.

The word restore comes up a lot in conversations about the Fortymile caribou herd. There’s restoring the herd to a robust population, and the herd restoring parts of its old range, but it’s equally important to restore people’s connections to the herd.

A few Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin citizens began hunting the herd again in the 2000s, but rebuilding relationships with the herd has been slow. There were generations of Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin who barely hunted the herd. Young people like Chase Everitt are changing that. “I just like seeing animals,” he says. “Even after the shot, it’s not the excitement of ‘I got one’ it’s ‘I get to see it more, see what it actually looks like, everything about it.’ ”

Chase describes his first time hunting the Fortymile caribou. He shot one caribou from a group of four, then the sound of the rifle echoing off the hills set the landscape into motion. Thousands of caribou stirred across the mountains ahead of him. The image sounds a lot like accounts I’d read from a century ago, when people spoke of mountainsides so thick with caribou that the landscape itself seemed alive.

Chris and Chase head back for Dawson. I drive another kilometre up the road, then pack a bag with camera gear and start bushwhacking. I head for the top of a hill, not far from where I’d seen caribou congregating earlier in the day. After a few minutes I break free from a tangle of alders into the clear. Soon a hundred caribou appear just ahead along the ridge. I duck down among a clump of spruce and wait. The caribou burst into a canter and jostle towards me. The herd passes within 30 metres of me. The air is heavy with the sounds of grunting and clicking tendons. Then they’re gone.

A Summer Spent at CPAWS

Written by Preet Dhillon, Conservation Intern

The COVID 19 pandemic proved a challenging year for many universities, as classes shifted from an in-person learning experience to online classes offered remotely. I found myself, along with other students, in a unique and new situation. Instead of attending classes and engaging with teachers and peers on campus, ‘campus’ became the desk in my room while classes were held on the screen of my computer. Come the month of May the remote school year had come to an end; it was time to go back home to the Yukon. After a year of learning online I was looking forward to spending a summer at CPAWS Yukon.

As I reflect on what I have gotten up to in these past few months, I am grateful for the opportunity to have had the position of conservation intern over the summer. Here you will find out how I spent my summer at CPAWS and what I was able to do.

I started out my summer helping Conservation Coordinator, Maegan Elliott, with fieldwork aimed to monitor the biodiversity of McIntyre Creek. I was able to learn about the methods used to capture the biodiversity such as motion trapping cameras, bat detectors and Autonomic Recording Units (ARUs). While setting up these systems we explored a variety of different areas such as soggy wetlands, tall pine and spruce tree forests, aspen groves and more! McIntyre Creek is an incredible area, filled with a variety of plant life and wildlife.

I enjoyed hiking through the McIntyre Creek area and exploring the diversity it has to offer, while learning of how the different methods work, how to set them up and the value that they hold in assessing biodiversity.

I enjoyed exploring McIntyre Creek throughout the summer, and I would encourage many others to do the same. I discovered McIntyre Creek to be a very diverse area, filled a with a variety of plant life, wildlife, and different natural landscapes. I was able to collaborate with the Yukon Conservation Society’s summer intern, as we worked on a booklet called “A Walk-Through McIntyre Creek”. This booklet features directions for a 2km hiking trail and information about the First Nations, natural history, plants, wildlife of McIntyre Creek and more!

Furthermore, with an interest on Yukon bumblebees, I was also able to monitor bumblebee diversity in McIntyre Creek. Blue vane traps were placed at a variety of sites in the McIntyre Creek area, for a few weeks. Each bumblebee was then identified by local biologist Syd Cannings. At one of the sites, I was able to encounter the Western Bumblebee listed as a special concern on species at risk. This allowed me to discover the importance species at risk have on larger scale.

Additionally, after a year away from the farmers market due to the pandemic, we were excited to make a reappearance as we greeted familiar faces and introduced ourselves to some new ones. I was able to spend each Thursday at the market along with other members of the CPAWS team, where we would provide information and updates to the public on CPAWS work. I enjoyed interacting and engaging people on their interests surrounding Yukon wilderness and the CPAWS organization. Despite the windy days that proved challenging when trying to keep displays put together, the farmers market was a delightful experience and would like to thank everyone that dropped by!

I find summers to take a very long time to arrive as we wait for them through the cold months. Interestingly, summers seem to end way sooner than you expect. I find my summer spent at CPAWS, to be similar. Although it was short and sweet, I am fortunate to walk away plenty of knowledge and am thankful for the CPAWS family who made it so great and helped me so much.

Protect the Peel digital archives project – a retrospective

Protect the Peel digital archives project – a retrospective

Written by Judith van Gulick, Operations Manager

The reason that CPAWS Yukon was founded in the early nineties, was to bring greater attention to conservation issues in the Yukon. More specifically, conservation in the early years was mainly focused on the Bonnet Plume river and the Peel watershed. In August 2019, the Peel Watershed Regional Land Use plan was signed.

How many documents were created during a campaign that took more than twenty five years to complete? The answer is: enough to almost fill up the entire basement of our office!

Archive work can often be perceived as mundane and tedious. Luckily we found an enthusiastic intern in early 2019, who spent many months creating a consolidated archive of all research documents, reports, communications between partners, and campaign visuals. The result was a well organized paper archive of the Protect the Peel campaign. Unfortunately, it still wasn’t that easy for staff members to search the archives or to locate information to use for current campaigns, nor were these important materials safeguarded from floods or fires.

It was a priority for our organization to digitize the archives for safekeeping – this would also enhance searchability and accessibility for staff and researchers outside of our organization. The Government of Yukon’s Community Development Fund (CDF) agreed with the importance of this project and decided to fund about half of the expenses. Thanks to CDF’s funding and ECO Canada’s Digital Skills for Youth wage subsidy, we were able to hire a Junior Digital Archivist, Asad Chishti, and could contract two professional archivists from the Yukon Council of Archives (YCA) to work together on this project. Those three individuals love archives!

The result of many hours of scanning documents, digitizing visuals, and completing the database, is a searchable index that is accessible to all CPAWS Yukon staff members. Staff can use keywords (tags) to search for documents and can easily click on the hyperlinks to bring them to the appropriate document. The wonderful thing about completing this project is that we can easily use past campaign materials to tell intriguing stories about CPAWS Yukon’s history, bring back memories from past successes, and use lessons that we learned in the past to build even better campaigns today and in the future!

Digitizing the archives already proved helpful to our community outreach team. Asad provided valuable and insightful input during land use planning campaign meetings thanks to their excellent skills in sourcing relevant information. Using photos, important quotes, and letters, which were singled out from the archives, Asad assisted the outreach team with the development of their campaign strategy and outreach plan.

All of this helps to contextualize how our work on future land use plans extends, borrows and remixes the lessons from the Peel Regional Land Use Planning process. This is something we hope to communicate in order for communities to prepare for land use planning in their regions.

Not only do we now have a digital archive of the Protect the Peel campaign, we’re also set up to add materials to the archives in the future. The YCA archivists led the writing of an archival policy as well as an appraisal policy, which gives our organization much-needed guidance in the process of building upon our archives. You might even say that we’re more excited about archives than we ever thought possible!

The digital archives are – for the moment – only directly accessible to our staff. We welcome you to contact us at info@cpawsyukon.org if you’re interested in a particular report, topic, or other detail from the Protect the Peel archives – we’re happy to help you find the information that you’re looking for!

Want to stay in the loop?

Sign up for our e-newsletter to stay up to date on all our work!

A Q&A with Chris Rider on the climate crisis

Recently, Yukon’s French language newspaper L’aurore Boréale interviewed our Executive Director, Chris Rider about to discuss the Climate Crisis.

The interview was done in English, then translated to French for the newspaper. We are posting the English language version, with permission from Sophie Delaigue and L’aurore Boréale.

1. When you look at this past summer (floods in the Yukon and extreme heat/fires in BC), do you think it’s our new normal?

I hope that the level of flooding we experienced this summer isn’t the new normal, but unfortunately I do think we can expect the Yukon’s weather to continue to become more and more erratic. Scientists are warning that the climate crisis means extreme weather events are going to continue to happen more frequently, and that means that unless the world takes action, flooding and fires are something we will likely see a lot more frequently in the Yukon. For a long time, people have said the costs of addressing climate change are too high. Sadly, we’re already beginning to see that the costs of not addressing it are even higher.

2. What is coming up in terms of climate action this fall, e.g. COP26, new policies, etc.?

I’ve been so inspired by the work that youth have been doing to address climate change in the Yukon. From the rallies organized by high school students to the Youth Panel on Climate Change and the Council of Yukon First Nations Youth Climate Action Fellowship, they are pushing for real change.

I’m also really excited by the growing focus on Indigenous-led conservation in Canada, including the federal government’s recent commitment of $166 million for the establishment of new Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA’s). This is a model for preserving land, where Indigenous governments and citizens are key decision makers when it comes to how the land and water is managed. It is a way of ensuring First Nations, Metis and Inuit people have control over the lands they’ve stewarded for millennia and it’s a model that I think we’re going to see a lot more in the next ten years.

Supporting Indigenous-led conservation is a big win for our climate, because keeping forests and wetlands intact can help to ensure carbon is captured and stored safely by nature. That’s why this is called a “nature-based solution” to climate change!

3. What are CPAWS Yukon top priorities for the next year?

Earlier this year, CPAWS Yukon and the Yukon Conservation Society commissioned some independent polling to learn more about Yukoner’s views on nature and the environment. We found that nearly 80% of Yukoners support strong targets for protecting nature. That was really exciting for us to see, and we will work to support First Nations across the Territory, to ensure that the Yukon is a leader in protecting our most valuable natural resource – plants and wildlife!

This includes supporting Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and White River First Nation citizens to protect important land and wildlife in the Dawson region, which is primarily the traditional territory of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in; helping to protect Chasán Chúa (more commonly known as McIntyre Creek) in the traditional territory of Ta’an Kwäch’än Council and Kwanlin Dün First Nation in Whitehorse; and supporting Na-Cho Nyäk Dun citizens to keep the Beaver River Watershed free from development.

4. If people could do just one thing to tackle climate change, what would that be?

We all know that there are plenty of things we can do to help tackle climate change – drive less, fly less, better insulate our homes, etc. – but ultimately most of the big changes will need to come from businesses and government. That’s why I think the single most important thing that we can do is to tell our politicians, and the brands that we engage with, that addressing climate change is something you care about. Tell them that climate change and protecting the environment should be their biggest priority, and that you won’t support them if you don’t see real action. If enough of us continue to do that, they will have to listen!

This was originally published en français in L’aurore Boréale. You can read the original here: http://auroreboreale.ca/des-solutions-fondees-sur-la-nature-pour-lutter-contre-le-changement-climatique/

Conservation from the Couch

Conservation from the Couch

An abridged version of this was published in What’s Up Yukon

Written by Randi Newton, Conservation Manager

Like many Yukoners, physical distancing meant I spent a lot more time than usual at home this spring. One of my highlights was catching up with local films on the Yukon Film Society’s streaming website, Available Light on Demand.

I was spellbound by Camera Trap, a short documentary that follows photographer Peter Mather as he tries to capture the perfect photo of the Porcupine caribou herd. Peter uses storytelling to advocate and inspire others to stand with the Gwich’in people and protect the herd’s migration route and calving grounds.

Watching Peter lug a heavy pulk across miles of soggy snow and carry expensive camera gear across streams of slippery snowmelt made my lazy evening on the couch feel even cushier. The end of the film shows the incredible images he was able to capture that will surely inspire conservation action.

As a teenager, I remember reading National Geographic and being inspired by similar stories of epic journeys in the name of conservation. Now I work for a conservation organization, and my typical journey is far from epic. Usually it’s from home to office and back, with an occasional stop at the grocery store. Lately my commute has been even shorter, from the kitchen to my laptop at the dining room table.

Even if you can’t undertake a marathon trek across the tundra, you can still support conservation. Writing letters and filling out engagement surveys are incredibly valuable. I call this “conservation from the couch”. These types of actions have advanced conservation efforts across the globe, including protection of the Porcupine caribou.

Two winters ago, oil exploration company SAExploration wanted to conduct an intrusive seismic survey in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The Gwich’in Steering Committee and the Sierra Club led a campaign in opposition to the oil surveys, and inspired over 250,000 people to make phone calls or send emails to SAEx. Bernadette Dementieff of the Gwich’in Steering Committee joined local activists to hand deliver boxes upon boxes of letters to SAEx’s headquarters in Houston, Texas. The thousands of calls, emails, and letters – all part of conservation from the couch – had a large collective impact. Public opposition and SAEx’s legal difficulties have succeeded in keeping seismic exploration out of the Arctic Refuge.

You don’t need to be an “expert” to advocate for issues that you care about. It can be intimidating if you don’t know exactly what to say but this shouldn’t stop you. The important thing is to tell your story, why you care, and what you hope to see. You don’t need to know all the policy jargon, or have navigated the regulatory spider web. For example, thousands of people called to “Protect the Peel”, and wrote why this was important to them. That was enough. Policy makers then translated this call for action into policy (if you’re curious, it translated to designating land management units in the Peel Watershed as Special Management Areas).

Of course, not everyone has time to draft up a personal response. People are pulled in many directions by everything else going on in the world. Because you may be pressed for time, many organizations, including the team at CPAWS Yukon, often provide template letters that you can sign and send in. Decision makers may not weigh these types of responses as strongly as personal letters but will still see that you care about an issue. One way you can have more impact is to use the template letter as a starting point and add your own message.

Feeling ready to flex your conservation from the couch muscles? Right now you can provide input on the Yukon Mineral Development Strategy, a strategy that could modernize mineral exploration and development in the territory. Because these practices touch so many facets of life, this is really a chance to have your say in what the Yukon’s future should look like.

If you’ve ever thought that some things about mineral development in the Yukon need to shift, this is your opportunity to say so. That might include modernizing our mining legislation, putting a pause on mineral staking when land use planning is underway, or ensuring that mining aligns with the Yukon’s commitments to climate action and biodiversity conservation. Mining issues related to social justice and public health may also be on your mind. If you’re interested, CPAWS Yukon created a list of seven recommendations for the strategy, available at https://cpawsyukon.org/yukon-mds/. You can read them from your couch and, if they resonate with you, use them as a starting point to write your own submission.

Remember, you don’t need to be an “expert”. You are the expert when it comes to your concerns, your values, and the future you want to see.

Thoughts & Key Recommendations on Whitehorse’s Official Community Plan

Thoughts & Key Recommendations on Whitehorse’s Official Community Plan

Written by Maegan Elliott, Conservation Coordinator at CPAWS Yukon, Heather Ashthorn, Executive Director of Wildwise Yukon, and Sebastian Jones, Fish, Wildlife, and Habitat Analyst at Yukon Conservation Society.

Header image by Maegan Elliott: Conservation Intern Preet Dhillon walks along a large wetland complex within Whitehorse city limits

The City of Whitehorse is seeking feedback on key policy ideas for the next Official Community Plan until August 31st. This high-level plan will provide overarching direction for the next 20 years, helping determine how Whitehorse addresses big issues—like affordable and just housing, charting how new development occurs, and ensuring that the future is shaped by the visions of the First Nations whose territories Whitehorse occupies. Our organizations encourage people to engage with the full scope of the Official Community Plan, but for the purposes of this blog we’ll focus on the parts of the plan that relate to wildlife habitat and climate change.

You can read about these key policy ideas, also called emerging directions, here and access the survey to provide your feedback here by August 31st. This blog post includes key recommendations to the City from three local environmental organizations: CPAWS Yukon, Wildwise Yukon, and the Yukon Conservation Society (YCS).

Key Recommendations from CPAWS Yukon

Overall, the directions laid out for the next Official Community Plan align with CPAWS Yukon’s climate action and conservation goals. The plan includes positive policy directions such as: finding ways to strengthen the circular economy, support low impact and efficient transportation, reduce wildfire risk, monitor and manage climate change impacts, improve our food security, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, densify housing development, maintain a network of green connections throughout the City, and look for opportunities to expand city parks beyond city boundaries with regional planning. CPAWS Yukon is also pleased to see the plan consider a collaborative approach to the conservation of McIntyre Creek, a significant wildlife area and wildlife corridor that passes through the city. However, we have a few key recommendations to offer:

- Consider the potential future need for wildlife underpasses or overpasses along high-traffic roads that are likely to be upgraded in the future, such as the Alaska Highway and Mountainview Drive.

- Ensure that further development within McIntyre Creek, such as a road, is removed from consideration before collaborative planning for the area is complete.

- Improve how wildlife attractants, like garbage and compost bins, are managed in the city and strengthen applicable bylaws, especially along green spaces.

- Follow the directions laid out in the Wildfire Risk Reduction Strategy. If forest is cleared for fuel breaks, ensure breaks are strategically located to ensure they’re effective and not simply a tool to clear land for development.

- Ensure alignment with directions laid out in Our Clean Future, Yukon’s strategy to respond to climate change.

Wildwise Yukon’s Key Recommendations

Wildwise Yukon is a not for profit society, established in 2012, that operates to prevent and reduce human-wildlife conflict in the territory through research, outreach and education programs. Wildwise Yukon’s recommendations for the Official Community Plan center on improved coexistence with wildlife in Whitehorse:

- Promote human-wildlife coexistence across city strategies.

- Include specific direction in the Official Community Plan for reducing human-wildlife conflict.

- All city planning processes must align to promote wildlife-human coexistence. The Official Community Plan should acknowledge that we live in wildlife territory and demonstrate that wildlife will be considered in all planning processes. For example, the Official Community Plan should:

- Outline the City’s intent to improve our waste management system so it does not lead to habituation and food conditioning of bears.

- Provide direction for Parks planning in a way that considers and avoids development in areas with optimal bear forage and historical human-bear conflict and maintains trails and campgrounds in a manner which decreases risks.

- Empower the strengthening of bylaws and regulations to ensure increased agricultural activity in the city doesn’t lead to increased human-wildlife conflict.

- Consider the use of ornamentals for city beautifications that are not attractive to bears or other wildlife.

- Empower revisions to municipal building code to require bear proof enclosures for waste storage in all new buildings.

- All documents should reference the Whitehorse Bear Hazard Assessment, which was co-commissioned by WildWise, the City, Yukon Government, Kwanlin Dün First Nation and Ta’an Kwäch’än Council in 2016.

Yukon Conservation Society’s Key Recommendations

YCS is a grassroots environmental non-profit organization, established in 1968. Through a broad program of conservation education, input into public policy, and participating in project review processes, we strive to ensure that the Yukon’s natural resources are managed wisely, and that development is informed by environmental considerations. Policy directions in the Official Community Plan contain numerous excellent ideas, and YCS hopes these suggestions are helpful:

- Towards Reconciliation:

- The Towards Reconciliation Policy Directions does reference “continued collaboration” with First Nations, but it does not define a formal role for First Nations in planning. We recommend that this is addressed, and that there is a clear plan for how the City of Whitehorse will ensure that Ta’an Kwäch’än Council and Kwanlin Dün First Nation are meaningful partners in all planning decisions.

- Climate Action:

- We are pleased to see that a community emissions inventory is proposed; this would be strengthened with measurable targets in line with the International Panel on Climate Change’s direction to massively and urgently reduce emissions immediately, and mechanisms for enforcement.

- There is an opportunity to reduce wildfire risk and advance Reconciliation by supporting First Nations led controlled burns.

- We are cautious about expanding agriculture lands as a means towards increased local food production; there are real ecological consequences to converting wild lands to agriculture, and given the amount of underutilized, and un-utilized agriculture land, this may not be a good approach.

- Winter Transportation should be part of a Winter City Strategy.

- Towards a Sustainable Mode Share:

- Achieving sustainable transportation is an excellent policy direction.

- The target to reduce single passenger traffic should aim to reduce the total number of trips in single passenger vehicles compared to today, not simply the proportion of trips as a whole.

- YCS suggests zoning and other incentives that will foster and even mandate vehicle free households.

- In our experience, neighbourhoods rarely include a network of walking/cycling/ski trails separate from road networks. Foot trails can pass between houses in a way that roads cannot, and can greatly increase the livability of neighbourhoods.

- Conservation of Natural Areas:

- We suggest that the Conservation of Natural Areas direction includes a commitment to a defined minimum percentage of lands set aside for conservation, rather than ‘a large percentage’. The setting of this percentage, and identifying which lands, is another opportunity for Reconciliation.

- Key wildlife corridors should be identified and protected, and wildlife crossing for busy roads should be planned for.

- The Yukon River Corridor extends from the Southern Lakes to the Alaska border northwest of Dawson City, and early signals from the Draft Dawson Regional Land Use Plan indicate that this corridor will be managed as a unit, primarily for conservation. YCS recommends a commitment to integrating the Yukon River corridor within Whitehorse municipal limits into the Yukon wide Yukon River Corridor Special Management Area.

- Strong Downtown and liveable areas:

- YCS supports the approach that directs development to the downtown core rather than towards a highway strip. A commitment to zoning that prevents contradictory decisions would put meaning to this policy direction.

- YCS supports the concepts of Urban and Neighbourhood centres and encouraging development adjacent to transportation routes.

- Targeting the Right Supply of Housing:

- Consideration should be given to Municipally owned and built housing, a model which has proven itself as a method of rapidly addressing affordable housing gaps in numerous countries.

- Intensifying Employment Areas:

- We applaud the direction to accommodate growth, rather than foster growth, and we agree with densifying development.

- Given that infinite growth on a finite land-base is impossible, no matter how excellent the planning, YCS suggest that Whitehorse consider ways to arrest the curve of growth, and to set a population target and methods to achieve it.

You’ve made it all the way to the end of the key recommendations from CPAWS Yukon, Wildwise Yukon and YCS! To gain some inspiration for your own feedback, scroll down and enjoy a cinematic masterpiece produced by the City of Whitehorse. Then, go take the survey to have your say in the Official Community Plan!

CPAWS Yukon’s Commitment to Reconciliation

For many years, CPAWS Yukon has been working hard to act in the spirit of reconciliation. It is work that arguably started when previous staff and leaders at the organization began to meaningfully collaborate with Na-Cho Nyäk Dun, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation and the Gwich’in Nations of the Northwest Territories, represented by the Gwich’in Tribal Council.

In recent years, working ethically to support First Nations has been something we have continued to focus on. Our team has committed to learning, through taking courses, internal training and conversations and direct teaching by Elders and other First Nations leaders across the Yukon. We are also particularly lucky that Anne Mease, a Selkirk First Nation Citizen with a Masters in Native Studies, works for CPAWS Yukon as our Outreach Coordinator.

Through all of this, the more we have learned, the more we have come to recognize just how much we still have to do.

So when, at the beginning of this year, Jared Gonet – a PHD candidate, former President of the Yukon Conservation Society & Taku River Tlingit citizen – approached us about collaborating on a reconciliation document, we were excited to start working on it.

At the time, we could not have predicted where the document would go, and how much I would learn through drafting it. The more we worked on it, the more important it began to feel. We knew that it was something we had to get right.

What you see here is the result of many, many hours of work. Its authors include Jared Gonet and Caitlynn Beckett (YCS board member), Anne Mease, Joti Overduin and myself. We also had an incredible amount of support and input from the board of CPAWS Yukon, whose input helped make it much, much better.

On May 31st, 2021, our Board of Directors voted to formally adopt this document. In doing so, they have acknowledging the work we have to do and we – as a staff and board – are making a firm commitment to action. Please hold us to it.

I encourage you to take the time to read this document, and we welcome any organization to adapt or copy it for yourself – though if you do, we ask you not to do it lightly. It can only be meaningful if we, as a sector, follow through on the actions we have committed to.

With that, I present to you: CPAWS Yukon’s Commitment on Reconciliation.

Our Commitment to Reconciliation

Reconciliation is about balance and healing between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples, including non-profit organizations. We are an environmental organization that is settler-founded and has a staff and board that remains mostly-settler. Our ways of operating have been, and are currently, influenced by the norms and customs that have been forcibly imposed since the European colonisation of Canada. This is important to recognize as it carries specific responsibilities in our path towards Reconciliation. It is our desire and our obligation to reconcile the colonial past with the present and into the future. CPAWS Yukon acknowledges the responsibility to support First Nations and the Inuvialuit to safeguard the land, water and air for future generations. We commit to specific actions to help with our path towards Reconciliation, though we acknowledge that we will not be the ones to determine if they were effective. We recognize that we are in the early stages of an important journey, and for this reason, this is a living document and it will continue to evolve as we learn.

- Follow a path towards Reconciliation.

- Learn from, and be accountable for any mistakes we make and have made. We will work to reinforce and expand positive efforts and approaches.

- Listen

- Be true partners with Yukon First Nations and other Indigenous Peoples as we seek to maintain species and places that shelter and provide for those species

- Continue to prioritize building and stewarding relationships with First Nations and Inuvialuit communities, citizens and governments. We recognize the responsibilities that come with these relationships and that trust is difficult to earn, but easily broken

- Recognize the history of colonialism that exists within conservation and environmental management and take action to ensure that it does not continue

- Create awareness about:

- The structures that were designed to foster and uphold colonialism, such as the Doctrine of Discovery and Terra Nullius. It is helpful that these ideas have been renounced both nationally and internationally, in particular by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and through UNDRIP, though the concepts tied to them are still used today and impede the path to Reconciliation;

- How the environmental sector can support the abolishment of colonialism.

We are still far from Reconciliation, and acknowledge the fact that it is ultimately not for us to decide what is considered true reconciliation. Understanding the damage done through past and existing colonial institutions and practices, there is still much to learn and much healing to be done. We recognize that this commitment is just a step in our ongoing journey. With this work, we hope we can play a small role towards Reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and we will play this role with humility, respect, and hope for a better tomorrow

Annual Report 2020-21

Welcome to our first annual report! We’re excited to give you a glimpse of everything that’s been going on within CPAWS Yukon for the past year, and hope you find this a helpful resource.