7 Easy Ways to Speed Up WordPress Backend

Looking to speed up your frustratingly slow WordPress admin panel? A fast and efficient WordPress backend is just as critical as a visually appealing frontend. Think of it as tuning up a sports car engine.

Looking to speed up your frustratingly slow WordPress admin panel? A fast and efficient WordPress backend is just as critical as a visually appealing frontend. Think of it as tuning up a sports car engine.

Written by Malkolm Boothroyd | August 6, 2023

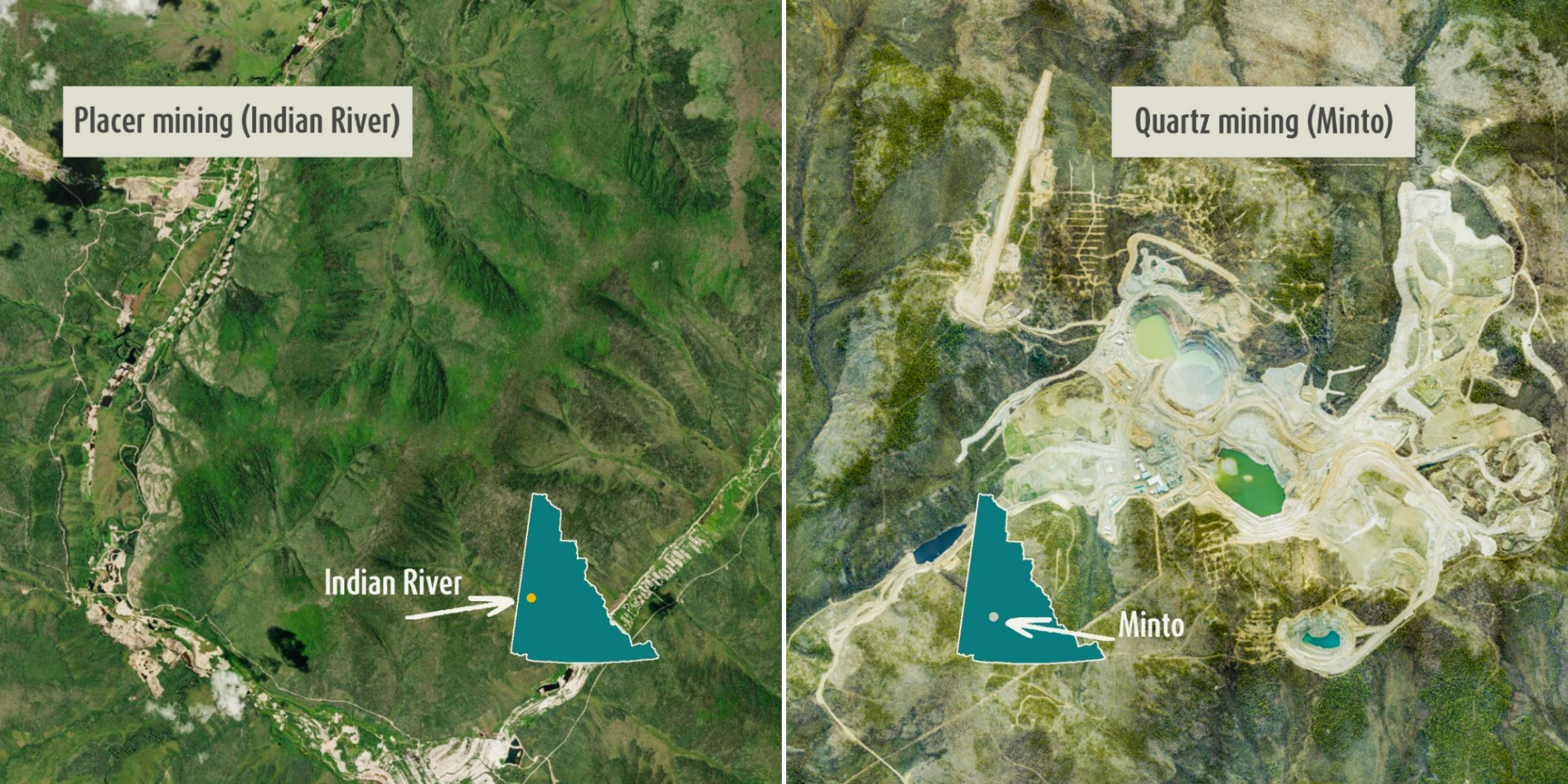

Photo from Google Earth, Minto Mine and Yukon River.

Read the full editorial as published in the Yukon News on August 6th, 2023.

—

This spring the Minto Mine shuttered, leaving dozens out of work and tens of millions in unpaid bills and royalties.

The Yukon public is on the hook for much of the clean up costs. Many explanations have been offered up for the financial struggles that ultimately sunk Minto.

People have blamed volatile copper prices, the pandemic and spring snowmelt straining the mine’s capacity to treat water. One contractor suggested investors were scared off when the Yukon government requested a higher security bond from Minto. Minto may have been the victim of volatile circumstances, but mining is a volatile business. One study found that around the world, as many as three quarters of mines close unexpectedly or prematurely.

There is a simple explanation for what went wrong at Minto. The company that bought Minto had no business owning a major mining operation and the territory’s outdated mining laws could do little to safeguard the Yukon against the inevitable collapse.

The Minto mine got a new owner in 2019. At the time of the sale, Minto had been operating for over a decade and was nearing the end of its life. Still, the mine was in reasonably safe hands, as far as covering environmental costs went. Back then, Minto was owned by Capstone Mining Corp. Today, Capstone is valued at nearly $4.5 billion, putting it among the world’s 100 wealthiest mining companies. Capstone certainly had the financial resources to care for Minto. It could have implemented the mine’s clean up and closure plan, and the Yukon public wouldn’t have had to foot the bill. Instead, the company chose to sell Minto. As Capstone wrote in annual reports, it sought “value maximizing alternatives” for Minto, and for the company to have “no further obligation with respect to the closure” of the mine.

Capstone found a buyer in UK-based Pembridge Resources. The two companies could not have been more dissimilar. At the time of the sale, Capstone was a fully fledged mining company that also operated mines in the US, Mexico and Chile. Pembridge had never operated a mine before.

Pembridge got off to a rough start. The company’s initial attempt to purchase Minto collapsed after the company failed to raise enough capital. Pembridge was eventually forced to take millions of loans from American hedge funds, in return giving up ownership of nearly 90 per cent of Minto. A Pembridge subsidiary, Minto Metals Corp subsequently took control of the mine.

Minto restarted production in 2019, but without functional water treatment facilities. Contaminated water steadily accumulated, while the mine’s water storage capacity shrunk, eventually falling below the minimum levels required by its water license. In 2022, due in large part to water treatment issues, the Yukon government requested an additional $18 million in financial security, which Minto failed to pay. That same year, Minto announced it would invest $8 million in water treatment, but was unable to resolve its water crisis. This spring Minto Metals’ Board of Directors resigned and the company abandoned Minto.

Still, not everyone lost out as a result of this mess. Pembridge’s CEO earned the equivalent of $1.5 million Canadian dollars the year of the Minto sale. Capstone sold Minto for $20 million US and got to walk away from the mine.

Just six years after Yukon Zinc walked away from the Wolverine Mine, the Yukon has been saddled with another abandoned mine to care for. There are parallels between Minto and Wolverine — both allowed too much contaminated water to pile up, both were plagued by financial hardships and both failed to pay tens of millions in financial security to the Yukon government. A report by the accounting giant PWC detailed what went wrong at Wolverine, parts of which could be cut and pasted into a report about Minto. For example, PWC wrote that Yukon Zinc was a small, risky company, whose profits were vulnerable to changes in metal prices. Yukon Zinc “allowed liabilities to increase at the site, a decision that was influenced by their financial difficulties.” According to PWC, the Yukon government was unaware of many of the financial troubles at Yukon Zinc. The firm wrote that the Yukon should be conducting comprehensive risk assessments of mining companies before granting them licenses.

The Yukon government wanted to see Minto’s life extended, even if it meant a more fragile company taking control of the mine. After Pembridge’s first attempt to purchase Minto fell through, the then premier told the legislative assembly that his government was “hoping that [Capstone] can strike a deal with Pembridge.”

Five years later, the public is responsible for cleaning up Minto. Many red flags might have appeared had there been a risk assessment on Pembridge Resources prior to the sale of Minto. Unfortunately, as currently written, the Yukon’s mining laws don’t require checking to see if a company is a financial disaster waiting to happen.

Hopefully the Yukon government’s lawyers are figuring out if Capstone, or any of the American hedge funds that bankrolled the Minto purchase, can be held accountable for some of the clean up costs. At the same time, the Yukon should make sure that this can’t happen again. The Yukon is in the midst of rewriting its archaic mining laws and new legislation should prevent risky companies from undertaking massive environmental liabilities. Before issuing permits, the Yukon government should assess the financial stability of the companies responsible. Mining companies with moderate financial risk should be required to post higher security in advance. Corporations with high financial risk should not get permits unless they can find more robust companies to guarantee their projects.

Money, of course, is only one dimension of mining. It’s impossible to put a price on salmon runs, healthy caribou herds or the connections that people hold with the land and water. Minto’s financial story is easier to work out, but we have to learn the right lessons from it. Some will try to paint Minto’s downfall as the result of exceptional circumstances. The truth is mines fail all the time. Companies like Pembridge shouldn’t be trusted to oversee massive environmental risks if they can’t withstand a couple of rough years. It’s time to update our mining laws to help ensure that more mines don’t end up in the hands of volatile companies.

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba, Communications Coordinator. Photos by Makolm Boothroyd.

April 6, 2023

Across much of the Yukon, boreal forests and wetlands stretch as far as the eye can see, crisscrossed by ancestral rivers that provide for the land, people, and wildlife. Threatening these rich wild spaces is the legacy of the Klondike Gold Rush, which lives on in the territory’s mining laws. These laws date back to the 1900s and prioritize short-term gains, reflecting the extractive history of colonialism on Indigenous land.

Now the Yukon government is creating a new minerals legislation, in collaboration with Yukon and Transboundary First Nations. The new mining legislation will cover the entire life of placer and quartz/hardrock mines, from prospecting to production to closure.

This is a once in a generation opportunity, so we want to make it as accessible as possible for you to share your vision for mining in the Yukon. Even if you’re not a mining expert, you’re an expert on your hopes and vision for the territory’s future. Mining has shaped and will continue to shape the Yukon, and this legislation needs to prioritize the territory’s long-term health and prosperity.

There are lots of terms, synonyms, and potential approaches related to mineral development. Here we’ll define some common mining terms you might come across. Once you’re ready to take action, check out our guide to completing the official survey. Responses will be used by the Yukon government as they continue developing the legislation.

Placer Mining: Placer mining is a way of extracting minerals (usually gold) that has settled in the bottom of water courses like rivers, creeks, and wetlands.

These minerals often lie beneath frozen layers of soil and gravel requiring miners to use excavators, bulldozers, and pressurized water to strip away vegetation, soil, and let the permafrost thaw.

Quartz/Hardrock Mining: Hardrock mining is where mining companies extract minerals from bedrock veins using large open pit or underground mines.

Extracting minerals from the rock often involves the use of chemicals that can be harmful if released.

Images from Google Earth. Graphic by Malkolm Boothroyd.

Free Entry System: Free entry grants any individual or company the right to stake a mining claim without the need for a permit or other authorization.

Mineral rights are automatically approved without consultation or consent from First Nations. These mining claims then hold tremendous leverage over land use planning decisions.

Acquisition: Rules about who can stake a claim and how.

Currently any adult can do so by pounding a few stakes into the ground and paying a $10 fee. Part of the free entry system.

Disposition: Rules for where mineral staking can happen and what mineral rights are granted.

Prospectors can stake a claim anywhere, unless the area has been withdrawn from staking (like designated protected areas). Part of the free entry system.

Mineral Tenure/Mining Claim: When an individual or company has tenure or a claim, they hold the rights to explore and develop minerals below the claim.

These are acquired through the free entry system and have to be maintained in good standing.

Exploration: Evaluating the mining potential of an area where a company has mining claims.

Exploration can involve building roads and cutting trails, disturbing wildlife with daily flights, building camps, and moving tens of thousands of tonnes of rock. Claim holders automatically have the right to explore, but specific exploration projects are subject to approval.

Mining roads cover Arch Mountain in the Kluane Wildlife Sanctuary.

Financial Security: Hardrock (and a few placer) mining companies provide financial security to cover the costs of reclaiming and closing their mine site in case they abandon it.

This security amount is paid before production begins and reassessed every 2 years. The Yukon has a long track record of underestimating security needed, leading to expensive taxpayer funded cleanups and environmental harm left unsecured.

Royalties: Royalties are payments made to governments by mining companies, recognizing that the public and First Nations own the rights to minerals and should benefit from their extraction.

Placer miners currently pay just 37.5¢ per ounce of gold (the same rate as the early 1900s) and quartz miners are only required to make payments once they start making a profit.

Tailings: Tailings are waste materials left over after mining and can include harmful chemicals and metals.

Hardrock tailings are left in large ponds or are sometimes dried and stacked. Reclaiming tailings is a challenging task and some tailings will require treatment indefinitely.

Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board (YESAB): YESAB is responsible for reviewing proposed mining projects, and recommending mitigations and whether or not a project should go ahead to the Yukon government.

The YESAB process is separate from the new mining legislation but links very closely to it.

Abandoned Wellgreen quartz mine, clean-up costs are an estimated $15 million.

Reclamation: Reclamation involves transitioning land to a different state after exploration and mining ends.

It’s usually impossible to fully restore the original ecosystem – simply too much has changed. The result is a different landscape where original values have been restored, replaced, or lost to different extents. Reclamation can involve filling in pits, recontouring the landscape, and planting vegetation. It’s expensive and hard to enforce, sometimes resulting in mines being abandoned.

Peat: Peat is a carbon-rich soil found in some wetlands that takes thousands of years to form.

Peatlands are vulnerable to placer mining because gold settles at the bottom or rivers and wetlands. When excavated, the peat decays and releases massive amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. Peatlands cannot be restored.

Permafrost: Permafrost is frozen soil that holds huge stores of greenhouse gasses like methane and carbon dioxide.

Typically we would say that permafrost is soil that is frozen year-round, but climate change and developments like mining are causing permafrost thaw.

Closure: The goal of mine closure is to return the site to a stable, non-polluting state and to meet reclamation goals.

This process takes many years. In the Yukon, a hardrock mine is considered closed when a Closure Certificate has been issued. Despite the number of mines that have operated in the territory, none have received this certificate.

Abandonment: When a mining company leaves a site without meeting the proper reclamation or closure measures.

Abandoned mines can pose significant risks to people and the environment, as contaminants and equipment are left unchecked. Reclamation and closure is then handled by the Yukon government with public funds.

The stages of placer mining show how in spite of the best reclamation efforts, natural peatlands can’t be restored.

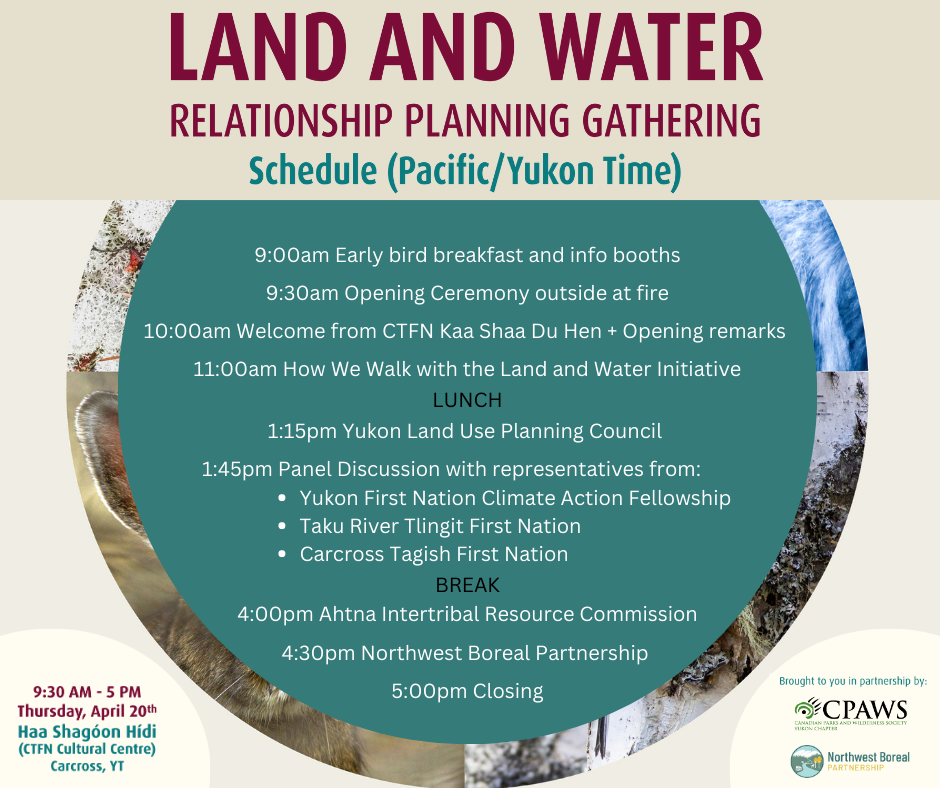

Event Details

Speakers attending:

Organized by CPAWS Yukon and the Northwest Boreal Partnership, this gathering is bringing people together to listen, share and learn about the intersection of efforts and opportunities around land and water planning, climate adaptation, conservation, and regenerative economies – with a highlighted focus on Indigenous-led and collaborative efforts.

We expect to bring together a diverse group of representatives from First Nation communities and governments, government agencies, funding groups, academic institutions, conservation groups, the tourism and business sector, and land planning and management organizations.

In addition to teaching and inspiring one another with examples of what is possible, we hope this gathering will help everyone work together on future land-water initiatives and planning in the North, across the nation, and cross-borders.

This all-day event will include lunch, snacks, and food for thought as we listen and learn together, and share thoughts on Indigenous-led stewardship initiatives, land and water relationship planning, regenerative economies, First Nation climate solutions, and cross-border initiatives.

Options for Attending

In-person:

Doors open at 9:00am for an early-bird breakfast and the event will begin at 9:30am. We aim to wrap up the event at 5pm. Please dress to be outdoors for portions of the day.

Driving Directions from Whitehorse: Drive East on the Alaskan Highway (1), turn right on the Klondike Highway (2 Southbound) following signs to Carcross. After 51.5km, Haa Shagóon Hídi will be on the left hand side of the highway. Expect it to take about 60 minutes to drive from Whitehorse.

*If transportation from Whitehorse is a barrier for you, please let us know so that we can assist you in joining the gathering. Email cdow@cpawsyukon.org

Virtual:

This is more than simply watching via zoom. This gathering is an interactive hybrid event, made possible by Gúnta Business. Gúnta business specializes in high-quality and highly interactive live-streaming, making these important community events accessible to all.

Written by Paula Gomez Villalba

Updated December 2022

Every year there are many opportunities to connect with nature, but getting started isn’t always so easy. Our forests and lands are home to many plants, animals, and a long history of how Indigenous peoples cared for and used them. We’re all learning— whether it’s names of plants budding after a long winter, or a new exciting way to stay active in the mountains.

This list highlights a few resources and spaces around the Yukon that we’ve found helpful in fostering connections with our wild spaces.

The Boreal Herbal: Wild Food and Medicine Plants of the North

Written by Yukon resident Beverley Gray, this book is an amazing guide to identifying and using plants found in the North. It includes colour photos and profiles on specific plants, many recipes, and instructions on how to preserve plants. Many Yukon public libraries have copies available to borrow.

Government of Yukon Guide to Hunting & Guide to Trapping

These Government of Yukon guides dive into the rules and regulations of harvesting wildlife, how to get licenses, and how to be safe and responsible. They also highlight key education courses and workshops.

Kwanlin Dün First Nations Justice Department

The Justice Department “delivers cultural recreation, outreach and healing programs and services to youth (ages 12 to 29), their families and caregivers, and the whole community for the purposes of reducing risk factors, revitalizing cultural and traditions and improving quality of life.”

Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre

The Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre is the cultural home of the Kwanlin Dün First Nation in downtown Whitehorse. It is a gathering place that hosts events and workshops, including a hide tanning camp and sewing circle.

Council of Yukon First Nations

The Council of Yukon First Nations offers health, medical, culture and language, recreation, and social support. Their mandate is to serve as a political advocacy organization for Yukon First Nations holding traditional territories, to protect their rights, titles and interests.

Yukon Aboriginal Sport Circle

The Yukon Aboriginal Sport Circle is a non-profit society dedicated to promoting Aboriginal sports and participation. They offer many different sports programs in Yukon communities, including Arctic Sports, Dene Games, and Archery.

Kwanlin Koyotes Ski Club

The Kwanlin Koyotes are a youth ski group based out of the Kwanlin Koyote Cabin in McIntyre Subdivision. Their mandate is to get kids out on the land, learning how to ski, and taking in the natural environment that surrounds us.

Photo by Malkolm Boothroyd.

Looking for a way to bring a bit more colour into summer? Join our colouring contest and submit your completed page to win!

The contest runs until September 7th and is open to kids of all ages. We have three prizes available, including a $50 Mac’s Fireweed Books gift card.

Download your colouring page and enter the contest by emailing a photo of your finished piece to info@cpawsyukon.org with your name and age. You can also drop off your completed colouring page at our booth at the Fireweed Community Market on Thursdays 3-7pm.

These colouring pages are samples from Hutch’s Yukon Trip: A Colouring Book Journey by Ainslie Spence, CPAWS Yukon’s 2022 intern. Join Hutch the husky on an adventure across the Yukon to some of the places CPAWS Yukon has been working to conserve now and for future generations. The book features colouring pages, activity sheets, fun facts, and Hutch’s wild tips!

We’ll be selling the books ($5) at the Fireweed Community Market on Thursdays, 3 – 7 pm in Shipyards Park in Whitehorse.

The fine print:

All entries must be emailed to info@cpawsyukon.org or given to us in person. By submitting your entry you are giving CPAWS Yukon permission to share it on social media (you may remain anonymous if you want – just let us know!).