New poll confirms Yukoners support nature conservation in Canada, the Yukon, and the Dawson Region

While it’s no surprise that Yukoners deeply value the territory’s lands, waters and wildlife, a new poll confirms that Yukoners support nature protection. The poll, conducted by Nanos Research and commissioned by CPAWS Yukon, shows that a strong majority of Yukoners (80%) support the federal government’s commitment to protect 30% of land in Canada. Nearly three quarters of Yukoners (73%) think the Government of Yukon should commit to protecting at least 30% of the territory.

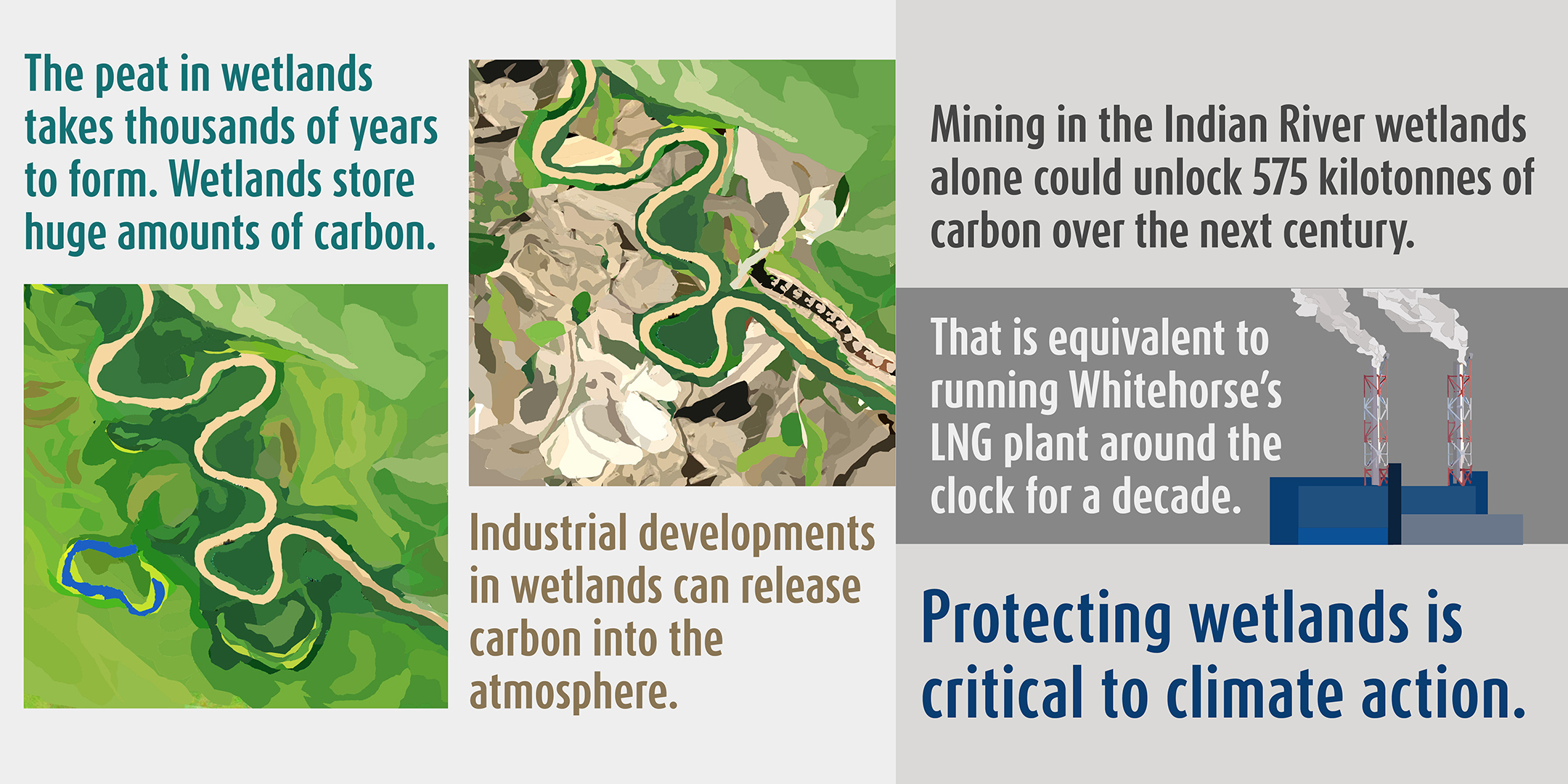

Currently 19.1% of the Yukon and 13.5% of Canada is protected. “Protected areas are an effective way to prevent habitat loss and fragmentation, two of the major causes of wildlife declines in Canada and around the world,” explained Randi Newton, Conservation Manager of CPAWS Yukon. “Indigenous-led conservation and land use planning offer clear pathways for protecting the lands and waters that make the Yukon so special.”

The poll is a strong indication that Yukoners are expecting more action from their governments to protect nature. The results are timely, as people from across the world are gathering at COP15, the United Nations’ biodiversity conference in Montreal, to set conservation goals to halt and reverse the loss of biodiversity.

The territorial government has not committed to conservation targets, despite the federal government pledging to protect 30% of land in Canada. However, the majority of Yukoners (66%) say they would be more likely to support a territorial government if it set a big and important nature conservation goal, like protecting and conserving 30% of land and water in the Yukon by 2030. Nearly two thirds (63%) say they would be more likely to support a Yukon political party if it proposed to increase territorial funding to create new protected areas. Only 16% were less likely to support a territorial party that made a commitment to do so (19% said it would have no impact).

“Commiting to nature conservation would help ensure the Yukon doesn’t sleepwalk into the same habitat and wildlife declines facing the rest of the country,” said Randi Newton. “Clear policy direction from governments would help support existing initiatives and Indigenous-led conservation efforts. Protecting at least 30% of the territory by 2030 is a very achievable goal if we simply follow the lead of land use planning and conservation initiatives from First Nations and the Inuvialuit.”

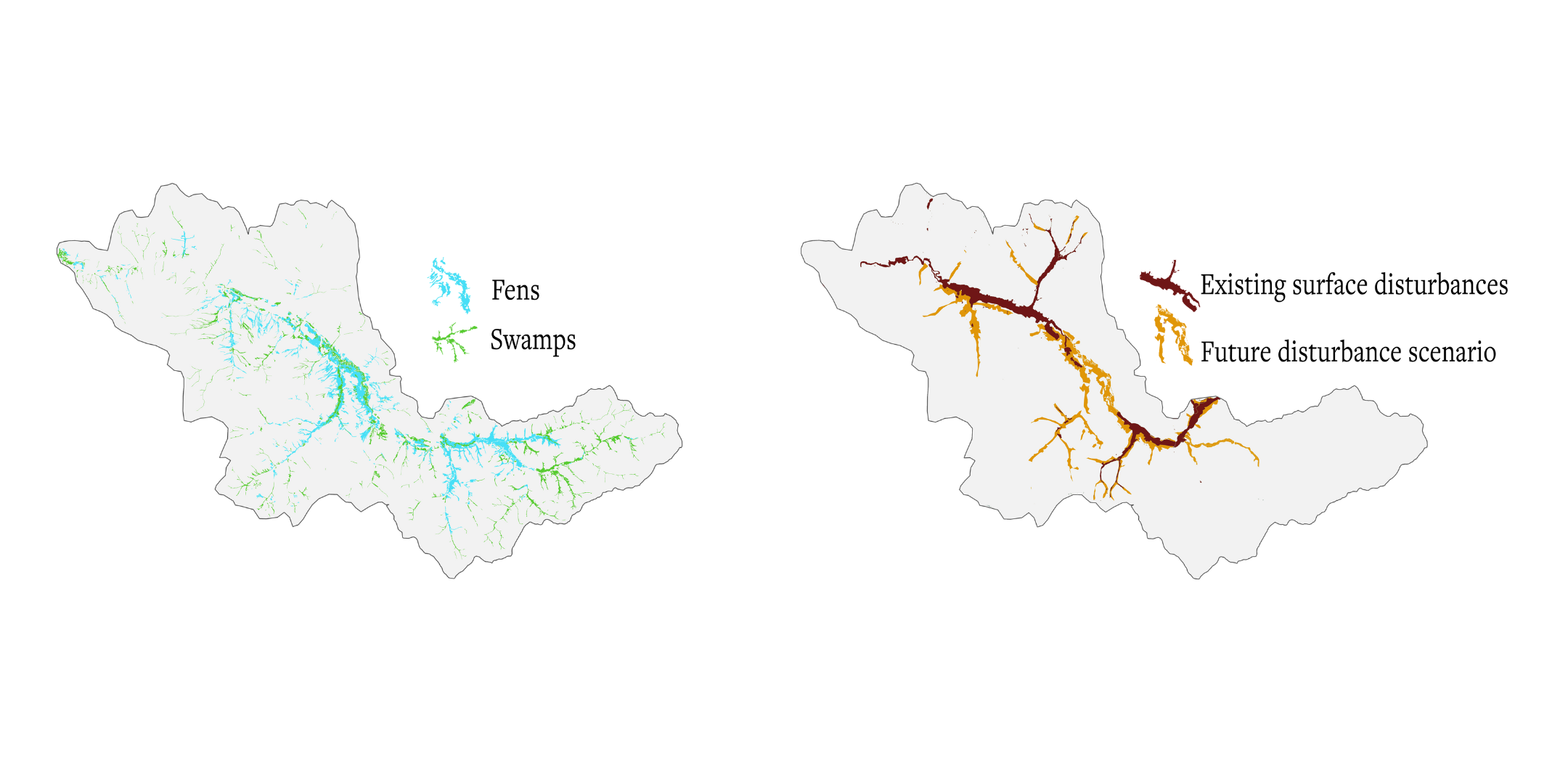

Yukoners also support conservation in the Dawson Region, where land use planning is ongoing. The Recommended Dawson Region Land Use Plan identifies nearly 40% of the region for protection, including the existing Tombstone Territorial Park. Nearly half (47%) of poll respondents favoured at least 40% protection, compared to 28% who favoured less than 20% protection.

“For many, Dawson is synonymous with mining and the Klondike Gold Rush, but this poll demonstrates that Yukoners also value Dawson for its superb wildlife habitat, beautiful rivers and mountains, and the cultural connections that run deeply with the land,” said Randi Newton.

Nanos Research conducted the poll through phone interviews with 410 Yukoners between November 4th and 14th, 2022. The results of the poll are accurate plus or minus 4.8%, 19 times out of 20.

Find a copy of the report here.

-30-

Contact

Adil Darvesh, CPAWS Yukon Communications Manager

867-393-8080 | adarvesh@cpawsyukon.org