2025: Our Year in Review

Written by Adil Darvesh, Communications Manager | December 23, 2025

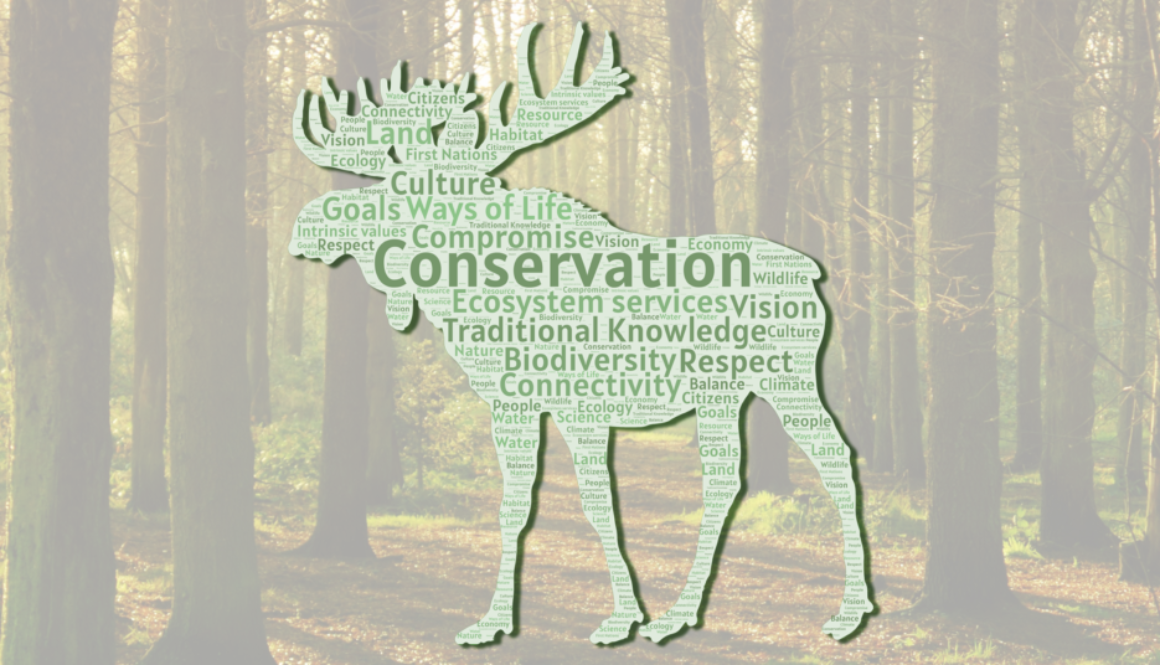

As the end of 2025 approaches on the horizon, it’s nice to take some time reflecting on the year that’s been. As with every recap, I want to highlight some of the major milestones or moments from different areas of our work and recognize that this work isn’t possible without the strong network of supporters, members, and donors. Thank you for another fulfilling year of conservation!

Peel Watershed

Protect the Peel. The last few years have shown us that while the Peel Watershed Regional Land Use Plan is signed and completed, there’s still work to ensure permanent protection. Around this time last year, we all gathered from Whitehorse, Mayo, Dawson City, Tsiigehtchich, and Inuvik to rally in support of the Peel from a proposed exploration project that went against the spirit of the Plan.

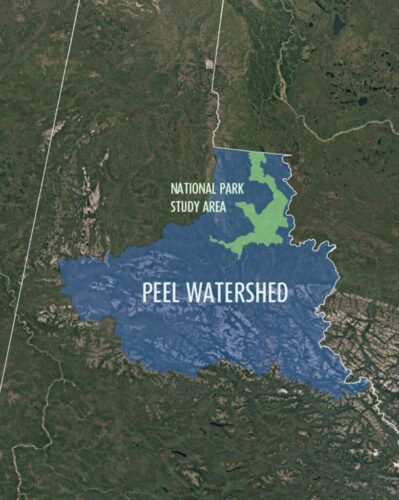

This year, however, we had some very positive news. After a year of undergoing a feasibility study, it was determined this year that a park in the Peel Watershed is feasible! On September 10th, 2025, the Gwich’in Tribal Council, First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun, Parks Canada, and Yukon government signed a Collaboration Accord to advance the project to the next stage – negotiating an establishment agreement.

“Indigenous-led conservation is foundational to any vision for a proposed national park in this area. This initiative presents a unique opportunity to uphold Indigenous self-determination, protect the integrity of the Teetł’it Gwinjik (Peel River) Watershed and support the continuation of cultural practices on the land. The parties are committed to working together toward a new national park that reflects shared values, protects biodiversity and honours Indigenous knowledge, culture and stewardship.” – Yukon government

The story of protecting the Peel Watershed is one that will undoubtedly be studied for years to come, thanks in large part to the tireless efforts of Thomas Berger – the main lawyer who represented CPAWS Yukon, Yukon Conservation Society, and First Nations in the case against Yukon government.

Against the Odds, a new release by Drew Ann Wake, shares some of the stories from Thomas Berger’s career, including his work to represent us for the Peel Watershed as well as his work during the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline inquiry.

Drew Anne Wake joined us in Whitehorse, Dawson City, and at the Northern Tutchone May Gathering this summer to speak about the book, share some anecdotes about her time with Thomas Berger, and of course, provide signed copies. This book tour was a way to share how far reaching his achievements were, as well as a way to pay homage to the many people who helped him on his journey.

Stewart River Watershed

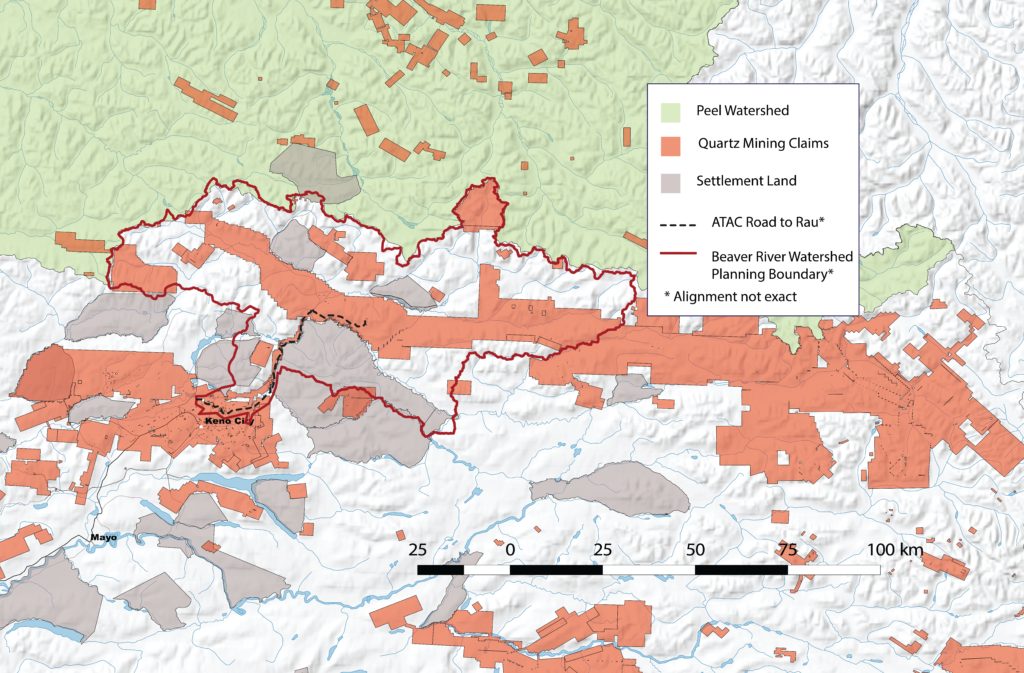

Nestled just below the Peel Watershed lies the equally beautiful and culturally significant Stewart River Watershed.

This year, alongside First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun (FNNND), we helped organize an on-the-land canoe trip through this iconic watershed. We held two canoe training sessions for participants and community members, one in Mayo and one in Whitehorse, in the leadup to the trip. These skill sessions helped trip participants prepare for all the wonderful challenges they would soon face.

Starting approximately 316km upstream of Fraser Falls, Joti Overduin, Randi Newton, and Nicole Schafenacker from the CPAWS team helped lead the group through meandering creeks and past rapids. Along the route, they stopped to take water samples with FNNND’s Land’s Department to keep tabs on quality of water in the watershed.

After 11 days, the group arrived at Fraser Falls – a place with deep connection to FNNND and the community of Mayo. Located about 40km north of Mayo, Fraser Falls was a place where citizens would fish and trap year-round, solidifying it as an important place in FNNND’s history.

From Fraser Falls, the group caught a ride on motorboats back to Mayo where they were welcomed back with dinner and a celebration.

During the welcome home celebration, Chief Dawna Hope from the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun shared that the Nation and Yukon government had agreed to a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to begin the process of regional land use planning.

This means that looking ahead, we’re going to be working to support conservation in the Stewart River Watershed and using the many stories, images, videos, and experiences to prioritize conservation in this scenic and significant watershed.

Mining Reform

The First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun continues to be in the spotlight as work to manage the disastrous Eagle Mine disaster continues. Earlier this year, an Independent Review Board released their findings on the technical cause for the failure which released of over 300 million litres of cyanide into the surrounding environment. CPAWS Yukon’s Campaigns Coordinator, Malkolm Boothroyd, flew over the Eagle Mine site earlier this year and put together a short video of what it looks like and what it feels like to be there.

The Independent Review Board outlines numerous ways in which the company and Yukon government failed in their duty to protect the land and water, and highlights specific ways in which the catastrophe could have been avoided. While the report is a good step towards understanding the causes of this specific failure, we must look broader at why failures continue to happen in the Yukon. From Wolverine, Faro, Mt. Nansen, and more, it’s clear that there are large systemic issues we need to address. A public inquiry would be a tool we could use to take a big picture approach to finding gaps in our mining process and combined with the work to update mineral legislation in the Yukon, we could hopefully avoid disasters in the future. We’ve joined the many numerous voices, led by FNNND in calling the Yukon government for a public inquiry that you can sign on to.

What could mining look like in a better system? That’s a question we sought answers to through the Transformative Mining and Alternatives webinar series we supported this year. Hosted by To Swim and Speak with Salmon and funded by Research from the Front Lines, this series explored Mining on Unceded Territories, Alternatives to Mining, Indigenous Governance and Salmon, and the Future of Mining in the Yukon.

I encourage you to take some time to review these webinars, they share perspectives from First Nations and Indigenous leaders, scientists who currently study mining processes land relations, lawyers, and more.

Following a mining project through the assessment process can be challenging to say the least. That’s something that was apparent to our Summer Conservation Intern, Tali Pukier, when she joined the team. Tali spent her summer coming up with a handy guide to navigate the mining review process through the various stages of assessment and licensing that they have to undergo. This tool is meant for everyone who cares about the future of the Yukon’s wild spaces, helping us understand what steps need to be taken, where we can have input, and how to best share our thoughts. Following a mining project through the assessment process can be challenging to say the least. That’s something that was apparent to our Summer Conservation Intern, Tali Pukier, when she joined the team. Tali spent her summer coming up with a handy guide to navigate the mining review process through the various stages of assessment and licensing that they have to undergo. This tool is meant for everyone who cares about the future of the Yukon’s wild spaces, helping us understand what steps need to be taken, where we can have input, and how to best share our thoughts.

Paddling the Pelly River

Name something better than pizza and a movie. After a successful Pelly River trip in 2024, the CPAWS team travelled to Ross River early in the year to premiere the short film Paddling Tu Des Des. Created by Jeremy Williams, the film highlighted special moments from the trip and the importance of connecting with the land and water. The pizza and movie night prompted helpful dialogue about the future that people want to see, and an opportunity to see Ross River youth on the big screen.

Our work with Ross River Dena Council has been growing over the last few years as we support their initiative for an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area in the Tū Łī́dlini (Ross River) area. Part of this work includes connecting with the land and water in different ways.

We helped organize a 3-day paddle from old Ross River to Faro this year, focusing on bringing families and youth to teach them skills highlighting the different ways people can connect with the land and water.

Over the winter, we’ll be working with videographer Christine Lin from Audubon to tell the story of the trip, so stay tuned!

Arctic Refuge

The Arctic Refuge had some unfortunate news this year. With President Trump’s second term in office, the U.S. administration has decided to undo much of the work that went into seeking protection in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the calving grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd.

Unfortunately for us, this means we have to go backwards, before the Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) which sought to correct some of the errors in the first Environmental Impact Statement.

Over the next year, we’ll be continuing to work with our allies in Alaska and the United States, as well as Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation and the Gwich’in Tribal Council to permanently protect this sacred area.

Chasàn Chùa / McIntyre Creek

What a momentous year for Chasàn Chùa! This year we had the incredible news that Kwanlin Dün First Nation, Ta’an Kwäch’än Council, the City of Whitehorse, and Yukon government officially designated Chasàn Chùa as a territorial park. This comes after decades of advocacy and work to highlight the importance of this wildlife corridor through the heart of Whitehorse.

Much of this success comes from so many of you who came out to City Hall, Care for the Creek events, and spoke up about the importance of this wildlife corridor.

Our work in Chasàn Chùa continued throughout the year with more workshops and guided walks throughout the region. From botanical drawing workshops to a habitat history and refresher, there are so many different ways to care for the creek, and we’re so grateful that you joined us to do so. We are thrilled to continue our work helping connect people to Chasàn Chùa through 2026.

Congratulations to Kwanlin Dün First Nation, Ta’an Kwäch’än Council, the City of Whitehorse, Yukon government, Friends of McIntyre Creek, Yukon Conservation Society, and all of you who helped achieve this moment.

Superbloom Anthology

How does art influence and connect us? Our Outreach Coordinator, Nicole, has been working on that question for many years.

Through a project supported by CPAWS Yukon and the Dechinta Centre, Nicole and fellow artist Krystal Silverfox began their project of Superbloom: Generating climate resilience in the North through art and community.

Inspired by the super bloom of fireweed in the aftermath of wildfires near Ethel Lake, Nicole and Krystal created an anthology of stories and art to exchange perspectives, knowledge, and expression through different artistic mediums from across the North. After numerous community visits, workshops, and presentations, the project was completed earlier this year.

Today, you can see Superbloom at the Yukon Art Centre main foyer where these stories can be viewed, listened to, and read by all.

Elections

Where do candidates stand on various environmental issues across the Yukon? This year we had both federal and territorial elections that would have lasting impacts on the environment and wild spaces around us.

CPAWS Yukon commissioned Nanos Research to conduct a poll on Yukoners to best understand what priorities voters have for the environment.

Unsurprisingly, Yukoners want better environmental regulations and more conservation.

The majority of respondents made it clear that the current regulations and oversight of mining isn’t strong enough, with over half believing that the mining industry does not behave in an environmentally responsible way. The majority of respondents also supported the establishment of Indigenous-led protected areas and requiring more First Nation approval for projects.

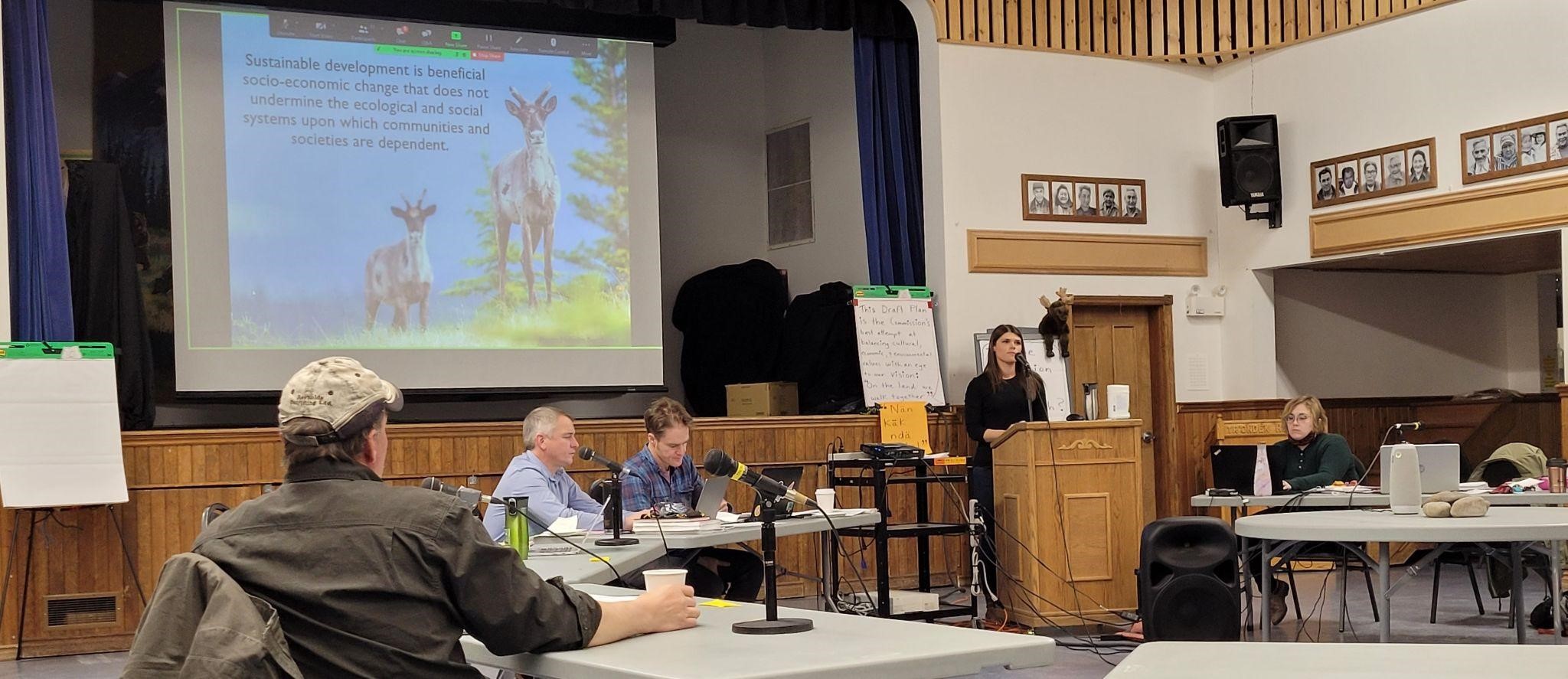

These results helped inform some of our questions to candidates at our All-Party Forum on the Environment during the territorial election.

Thank you to everyone who participated by submitting a question or showing up to listen to the responses at the forum.

Events

This was an especially busy summer for our team, hosting events across the territory and connecting with so many of you. From Salmon Appreciation Day at the Fish Ladder, where our Communications Coordinator, Paula, shared some of her work to map the different watersheds in the Yukon, to an art exhibition for the Superbloom anthology at the Yukon Arts Centre, it has been such a joy to connect, listen, and learn from all of you.

We can’t wait to keep the momentum going in 2026!